Sandra Newman

Sandra Newman, author of The Men (a book The Guardian is selling on their bookshop), has been looking at different works of fiction about men being banned from society or ceasing to exist.

The article describes the plot of some of these “female utopias,” and offers a glimpse into the sick yet childish minds of these women. Then, it mentions a few of the more recent books, which appear to be significantly more deranged.

Newman writes for The Guardian:

All the men are gone. Usually this is conceived as the result of a plague. Less often, the cause is violence. Occasionally, the men don’t die and the sexes are just segregated in different geographical regions. Or men miraculously vanish without explanation.

Left to themselves, the women create a better society, without inequality or war. All goods are shared. All children are safe. The economy is sustainable and Earth is cherished. Without male biology standing in the way, utopia builds itself.

I’m describing a subgenre of science fiction, mostly written in the 1970s-90s. It was once so popular it was almost synonymous with feminist SF. In 1995, when the Otherwise Award, a literary prize for “works of science fiction or fantasy that expand or explore one’s understanding of gender”, gave five retrospective awards, four of the works were set in such worlds: Suzy McKee Charnas’s Motherlines and Walk to the End of the World, and Joanna Russ’s The Female Man and When It Changed. The fifth was Ursula K Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, about a world whose inhabitants are all of the same sex.

Recently there has been a revival of the genre in radically different form, with titles including Lauren Beukes’s 2020 novel Afterland, Christina Sweeney-Baird’s 2021 thriller The End of Men, and my own new release, The Men. I think the way that these contemporary novels diverge from their earlier counterparts tells us something useful about gender politics in the 21st century. Part of the story, too, is a growing opposition to the basic premise, a conflict in which my novel has been recently embroiled.

The women-only utopia has a modest prehistory, going back to the myth of the Amazons and early feminist works such as Christine de Pizan’s 1405 The Book of the City of Ladies. But in its strict form as a single-sex utopia, it begins with Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland of 1915. Here, in an uncharted and unspecified wilderness, three male explorers stumble on a plateau the local “savages” fear as a realm from which no man returns. With their aeroplane, they are able to land there, and are instantly taken prisoner by the all-female inhabitants. The book then becomes a tour of the features of the women’s ideal society.

Women excel in all occupations. Older women gain prestige instead of losing it; the women are physically formidable and easily subdue their male captives. Charmingly, the narrator says of the national costume: “I see that I have not remarked that these women had pockets in surprising number and variety.” Their babies never cry.

Much less charmingly, we’re assured the Herland women are Aryans, and their society is focused on the perfection of their race. In fact, many of the hallmarks of fascism are here: the paganism, the obsession with cleanliness, the emphasis on gymnastics, the eugenics. The Herlanders also have no erotic or even romantic feelings for each other; they have bred those dirty things out.

The golden age of the genre, roughly coinciding with the era of second wave feminism, could scarcely be more different. Here the keynote is freedom, and lesbian polyamory is the order of the day. Solo travel features prominently: the authors are captivated by the idea of women hiking alone into the wilderness without the threat of rape. No regret is expressed about the loss of men, which is always in the distant past. Indeed, the topic is often treated with a bracing gallows humour.

Go hike alone, harpies, and see what you find.

Men are so good at shielding women from reality that women can’t imagine something being a threat to them, similar to how toddlers are oblivious to the daily challenges of their parents.

Joanna Russ’s novel The Female Man (written in 1970 but first published in 1975) is considered the masterpiece of the genre. Here, four versions of the author inhabit four parallel worlds. One is ours, where the protagonist is Joanna. The second is a more conservative New York, where the anxiously conventional Jeannine works to catch a husband she doesn’t truly want.

The third world is Whileaway, Russ’s utopia, where all men died of a plague 800 years earlier. Here, Janet fights duels, roams the wilderness, and is cheerfully promiscuous while adoring her wife, Vittoria, who, she boasts repeatedly, is much admired by Whileawayans for her big ass. Whileaway is a joyous, irreverent creation. Russ makes no apologies for stocking it with her own predilections (we’re left in no doubt of her opinion of big asses). Its people grumble all the time and are often jerks; it is above all things free – though it does have capital punishment for people who don’t do their share of the work. Even if it’s not your idea of paradise, you never doubt Russ would be happy there, which is more than you can say for most utopias and their creators.

…

The 21st-century revival is a very different animal. First, instead of being a dimly remembered political event, the mass death comes now. It has no good aspects. Men die horribly in front of us. Women are plunged into collective grief. Technological society falls apart for lack of skilled workers, and the world goes into decline. Women, meanwhile, are just as violent as men, and no more cooperative or empathic. The only result of generations of indoctrination into female roles is that girls are crap at engineering.

…

In Lauren Beukes’s 2020 novel Afterland, a threatened male is again the focus, after 99% of all male humans are killed by a flu that triggers prostate cancer. Survivors are incarcerated by the government and prevented from reproducing until a cure is found. The few free men are pursued by baby-hungry women and hunted by profiteers who want to harvest their sperm. The main character has broken her son out of a research facility and is fleeing with him through a post-apocalyptic world.

…

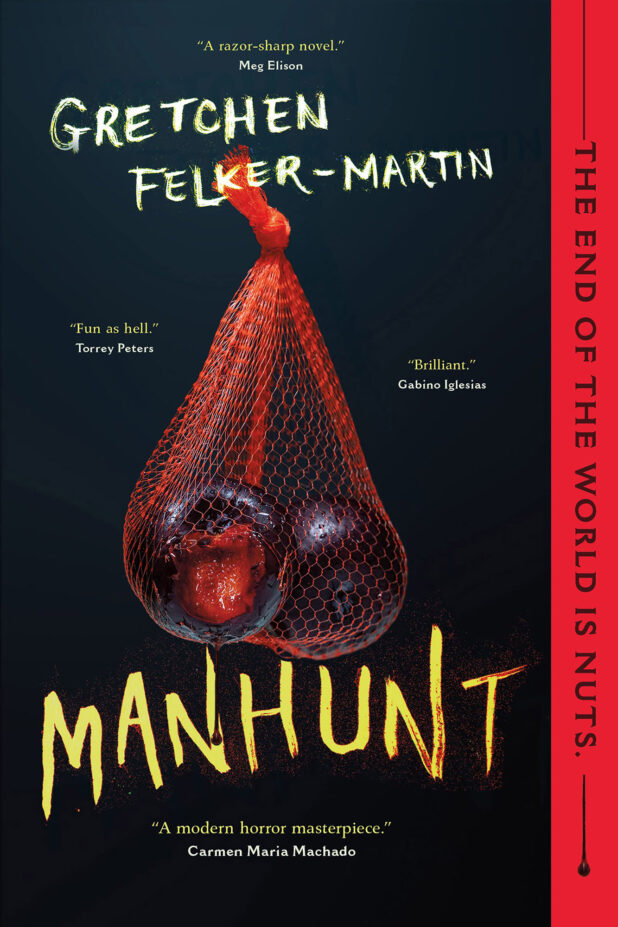

Even a recent book by a trans author, Gretchen Felker-Martin’s Manhunt (2022), has drawn criticism online. In this novel, a plague transforms men into mindless, cannibalistic monsters who roam the woods, raping and killing. Trans women must stave off transformation by constantly taking hormones they can only get by killing men and eating their testicles. Meanwhile, they’re being hunted by TERFs (trans-exclusionary radical feminists), who see them as man-monsters waiting to happen. The book is written to graphically convey the terror of transphobia. Still it’s been attacked by some on Twitter for its bioessentialist premise. Although producers of the TV version of Y: The Last Man hired trans writers to make the story more inclusive, it too was considered problematic.

Women are literally worse than Islamic terrorists.

They’re planning to kill us all.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History