Brenton Sanderson

Occidental Observer

January 28, 2016

Götz Aly’s selective application of his “pathological envy” thesis

While asserting that German hostility toward Jews has its origins in a pathological “envy,” as a fervent leftist Aly would never extend this line of reasoning to account for the hostility of American Blacks or other non-White groups toward Whites. Aly can safely posit that “intellectually inferior” Germans who “lacked confidence in their identity” had an envy-driven hatred for “intellectually superior” and upwardly mobile Jews, yet never assert that intellectually inferior Blacks have an envy-driven hatred for intellectually superior and upwardly mobile Whites. Instead he would doubtless affirm the bogus narrative that Black hostility to Whites is a legitimate response to an insidious White “racism” that has impeded their social and economic advancement. This, of course, is despite that fact that this supposedly ubiquitous and malign force has somehow failed to hinder the social and economic advancement of East Asians in Western societies.

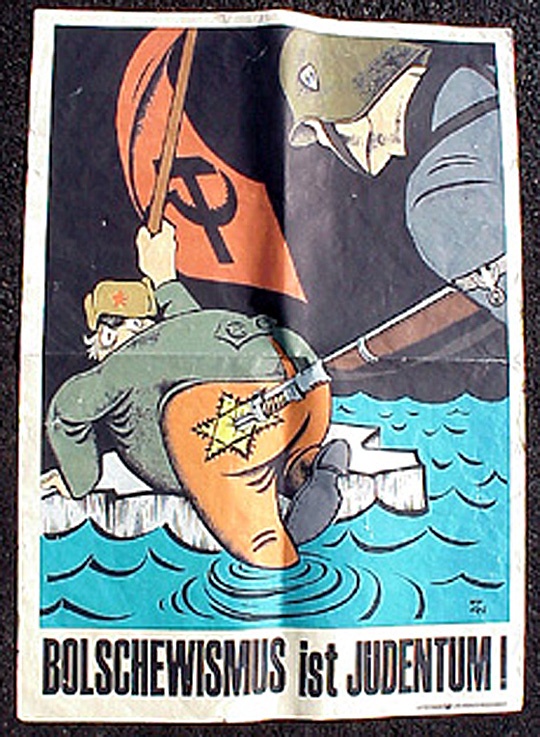

A National Socialist poster: “Bolshevism is Jewry”

Nor would Aly extrapolate his pathological envy thesis of intergroup hostility to explain the vastly disproportionate Jewish participation in the Bolshevik Revolution and the other oppressive communist regimes of Eastern Europe. This despite that fact that, in response to legal restrictions in Tsarist Russia that limited their economic and educational opportunities, millions of Jews gravitated to Zionism and Communism. That envy and resentment were key factors behind the overwhelming Jewish attraction to radical left was obvious to Norman Cantor who noted:

The Bolshevik Revolution and some of its aftermath represented, from one perspective, Jewish revenge. During the heyday of the Cold War, American Jewish publicists spent a lot of time denying that—as 1930s anti-Semites claimed—Jews played a disproportionately important role in Soviet and world Communism. The truth is until the early 1950s Jews did play such a role, and there is nothing to be ashamed of. In time Jews will learn to take pride in the record of the Jewish Communists in the Soviet Union and elsewhere. It was a species of striking back.[i]

Indeed a huge weakness of Why the Germans? Why the Jews? is the total neglect of the Jewish-Communist symbiosis and how this contributed (independently of envy at Jewish social advancement) to rising support for the NSDAP and other “anti-Semitic” political parties in Germany. It is common knowledge that when, after the chaos of World War I, revolutions erupted all over Europe, Jews were everywhere at the helm. One of Hitler’s most oft-repeated themes in the 1920s was the deadly threat that a “bloody Bolshevization” posed to Germany. In 1928 Hitler wrote:

The goal is the destruction of the inherently anti-Semitic Russia as well as the destruction of the German Reich, whose administration and army still provide resistance to the Jews. A further goal is the overthrow of those dynasties that have not yet been made subordinate to a Jewish-dependent and led democracy.

This goal in the Jewish struggle has at least to some degree been completely achieved. Tsarism and Kaiserism in Germany have been eliminated. With the help of the Bolshevik Revolution, the Russian upper class and also the national intelligentsia were — with inhuman torture and barbarity — murdered and completely eradicated. The victims of this Jewish fight for dominance in Russia totaled twenty-eight to thirty million dead among the Russian people. Fifteen times as many as the Great War cost Germany. After the successful Revolution he [further] tore away all the ties of orderliness, morality, custom, and so on, abolished marriage as a higher institution, and proclaimed in its place universal licentiousness with the goal that through this disorderly bastardy, to breed a generally inferior human mush which itself is incapable of leadership and ultimately will no longer be able to do without the Jews as its only intellectual element.[ii]

Another National Socialist source noted that: “Only those who have experienced that period of Jewish terror and slaughter, the murder of hostages, plundering and acts of arson [in the Munich communist uprisings of 1918–1919], are able to realize why Munich became the birthplace of National Socialism, whence the movement spread to other parts of Germany, and finally put an end to Jewish domination.”

Despite the centrality of the threat of “Jewish-Bolshevism” as part of the National Socialist platform, Aly completely ignores the whole topic because it simply doesn’t fit into his “pathological envy” theory of German “anti-Semitism.” In a work of some 304 pages purporting to analyze the origins Hitler’s popularity, the word “communism” rates a mere three mentions.

No mention of Jewish ethnic networking

In addition to his lack of consideration of how the very real fear of communism contributed to support for the National Socialists, another key weakness of Why the Germans? Why the Jews? is the lack of any discussion of the role of Jewish ethnic networking in the rapid social and economic advancement of Jews at the time. Jewish historian Jerry Muller acknowledged in his book Capitalism and the Jews the importance of Jewish ethnic networking contributing to Jewish upward social mobility, observing that “the obligation to look after fellow Jews was deeply embedded in Jewish law and culture, and it existed not just in theory but in practice.”[iii] A recurrent theme in Germany throughout the nineteenth century was how, if unchecked by the state, Jewish ethnic networking invariably led to their monopolization of entire industries and professions, and how this harmed German interests.

In 1819, for instance, the German writer Hartwig von Hundt-Radowsky noted that the anti-Jewish “Hep Hep” riots that year in southern Germany were precipitated by “the rights granted to Israelites in many states” which led “to the poverty and malnourishment that prevails in many regions since the Jews choke off all the trade and industry of the Christian populace.” He noted that the success that Jews recorded “in all profitable businesses ever since several states, guided by a misunderstood humanism, accorded them the freedom to choose their own trades, which is also a license to plunge Christians into misery.”[iv]

Around the same time the German academic Jakob Friedrich Fries likewise warned of the dangers that Jewish ethnic networking and nepotism presented for the native population, pointing out that “the Christian merchant, who stands alone, has no hope of competing.” Citing the example of Jews in the city of Frankfurt, who had been released from the ghetto in 1796 and had risen rapidly up in society, he warned: “Allow them to continue for a mere forty years or more, and the sons of the best Christian houses will have to hire on as their manservants.”[v]

The economist Friedrich List argued in 1820 that the state had the right and duty to protect the native German majority from Jewish economic domination and exploitation.[vi] Legal restrictions on Jews were lifted in the Grand Duchy of Posen in 1833, a region with a significant Jewish population. Soon thereafter a citizens’ committee on Jewish affairs noted that following the easing of restrictions it had not taken long for Jews “to take over high roads and market squares and dominate commerce and industry.” If they were given full citizenship rights, the committee argued, “almost all the towns and villages in the Grand Duchy would come under the exclusive administration of Jews.”[vii]

In the Kingdom of Saxony the general populace pressured the royal family to maintain anti-Jewish restrictions on certain types of economic activity. Dresden allowed “at most” four Jewish merchants, lest commercial streets “swarm with Jewish salesmen and trade fall into Jewish hands” Local civic leaders warned that any easing of restrictions would result in “Jews inundating the entire country so that soon farmers wouldn’t be able to sell a single calf without Jewish involvement.”[viii]

Kevin MacDonald notes in A People That Shall Dwell Alone that from “the standpoint of the group, it was always more important to maximize the resource flow from the gentile community to the Jewish community, rather than to allow individual Jews to maximize their interests at the expense of the Jewish community.”[ix] He makes the point that the propensity of Jews to engage in “tribal economics” involving high levels of within-group economic cooperation and patronage confers on these groups “an extraordinarily powerful competitive advantage against individual strategies.”[x] The power of this strategy was evident by 1914 when Jews earned five times the income of the average German.[xi]

In 1924, the German economist Gustav Schmoller argued in favor of only admitting small numbers of Jews to the higher ranks of the military or civil service. Otherwise, he feared, “they would swiftly develop into an intolerant dictator of the state and its administration. … How many cases have proved the truth of the prophecy that once you admit the first Jewish full professor, you’ll have five of them or more in ten years’ time.”[xii] In the same year, a delegate to the Bavarian parliament, Ottmar Rutz, noting this tendency and how it had resulted in the Jewish domination of the faculties of Bavarian universities, pointed out that “every Jewish professor and every Jewish civil servant keeps down a descendant of the German people. This sort of exclusion is what’s really at stake. It’s not a matter of insulting or attacking one or another descendant of the Jewish people. This has nothing to do with all of that, and nor do my petitions. This is solely about productively promoting the descendants of the German people and protecting them from exclusion.”[xiii]

Jewish overrepresentation among the learned professions was then, and is now, of such a magnitude that it cannot be accounted for solely on the basis of higher IQ and cultural differences alone — but was and is massively a product of Jewish nepotism. The role of Jewish ethnic networking in the vast overrepresentation of Jews at elite universities in the United States has been revealed by recent studies which have proved that Jews are represented at the Ivy League far beyond what would be predicted by IQ, whereas Whites of European descent are correspondingly underrepresented. For any given level of high IQ, non-Jews far outnumber Jews in America. For example, there are around 7 times as many non-Jews as Jews with an IQ greater than 130 (an IQ typical of successful professionals), and 4.5 times as many with IQ greater than 145. Obviously, there are not seven times as many non-Jews as Jews among elites in the elite sectors of the U.S. — quite the opposite. Would the situation, given the strength of Jewish ethnocentrism, have been any different in Germany in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries?

Virtually no mention of Jewish cultural subversion as a cause of “anti-Semitism”

As well as completely ignoring the crucially important phenomenon of Jewish ethnic networking, Aly fails to acknowledge the link between disproportionate wealth and disproportionate political, legislative, media and cultural influence, and how this influence was wielded by Jewish elites to reengineer German society in their own interests. Ethnic competition doesn’t only exist in the economic realm but in the cultural and political realms. Resentment fuelled by wealth disparities is only a part (albeit a highly significant part) of a multifaceted picture.

Kevin MacDonald has often noted that it wouldn’t matter if Jews were an economic elite if they were not hostile to the traditional people and culture of the West. The unfortunate reality is that they are hostile, and this hostility has existed for millennia. In Separation and Its Discontents he notes that the heightened level of resource competition between Germans and Jews, especially after 1870, “resulted in very large Jewish overrepresentation in all the markers of economic and professional success as well as the production of culture, the latter viewed as a highly deleterious influence.”[xiv] In his German Genius, Peter Watson observes that after 1880, and especially after the Dreyfus trial in France in 1893, “the Jews were increasingly identified as Europe’s leading ‘degenerates.’”[xv]

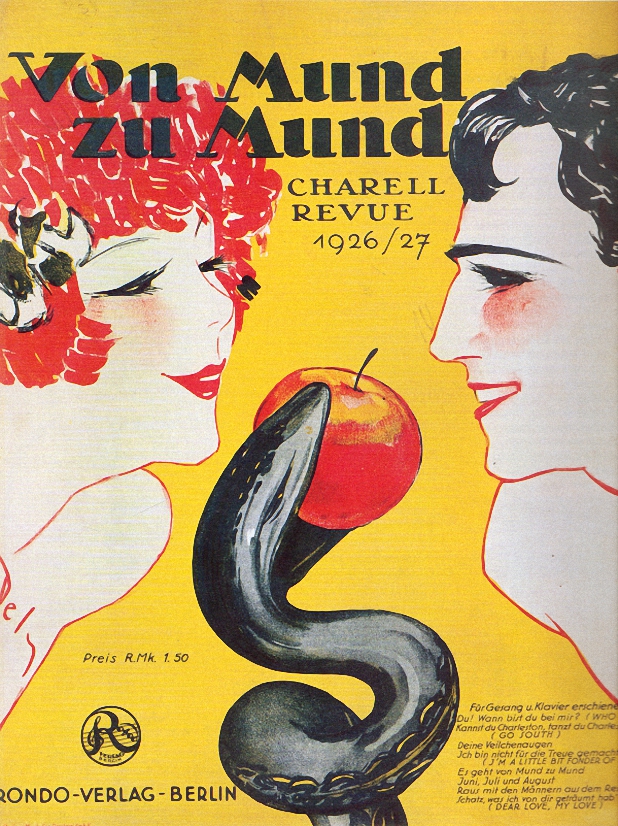

A National Socialist source from 1938 points out how “the disintegration and decay of German intellectual life under Jewish supremacy was most apparent and assumed their crudest aspects in the sphere of light entertainment art.” When, in the unstable political aftermath of Germany’s defeat in 1918, at a time when all barriers of law and order had broken down, “a veritable storm of Jewish immoral literature, obscene films and plays then broke over Germany.” The Berlin Revue proprietors who “were Jews without a single exception” offered the public “veritable orgies of sexuality and licentiousness. All realities of life were regarded from the one and only aspect of erotic desire and its satisfaction.” Berlin quickly assumed the mantle of “the most immoral town in the world.” The increasing spread of indecency and immorality forced the government in 1926 to “take constitutional steps for the suppression of filthy or otherwise low-grade literature.”

Revue poster from the Weimar Republic

The themes of Jewish moral, cultural and political subversion permeate the speeches and writings of Hitler and other leading National Socialist figuress. In Mein Kampf Hitler argued that the Jewish influence on German cultural life largely consisted in “dragging the people to the level of his own low mentality.” Likewise he recalls how he once asked himself whether “there was any shady undertaking, any form of foulness, especially in cultural life, in which at least one Jew did not participate?” and later discovered that “On putting the probing knife carefully to that kind of abscess, one immediately discovered, like a maggot in a putrescent body, a little Jew who was often blinded by the sudden light.”[xvi]

In a brief departure from his “envy” theory, Aly himself acknowledges the prevalence of the belief that Jews, through the insidious political and cultural influence they exerted, were destroying mainstream German culture, and that this belief, which spread through all social strata “became a mass phenomenon and paved the way for the racial anti-Semitism at the core of the National Socialist worldview.”[xvii] According to this worldview, “At the close of the emancipation era in Germany, the Jews enjoyed a practical monopoly of all the professions exerting intellectual and political influence. This enabled them to stamp their entirely alien features on the whole public life of the country.”

One of the ways that racial and ethnic groups do battle for position is through controlling the thought and ideas that go into the minds of their competitors. That explains the invariable push by Jews to exercise domination and control over the media and entertainment industries. They realize that media influence is an incredibly important aspect of ethnic competition in the modern world: filling the heads of your ethnic competitors with things that are not true or which are inimical to family life or other adaptive behavior among non-Jews but which help your group to thrive. Those non-Jews who are aware of what is going on naturally resent this waging of ethnic warfare through controlling the public flow of information — and the Germans were no exception.

The German media in the years before 1933 was almost entirely in Jewish hands. The largest circulation newspapers, the Berliner Morgenpost, the Vossische Zeitung, and the Berliner Tageblatt, were owned by the Jewish Ullmann and Mosse companies, and were overwhelmingly staffed by Jewish editors and journalists. The Marxist press, most prominently including newspapers like Vorwärts, Rote Fahne, and Freiheit was likewise under Jewish control. The Jewish essayist Moritz Goldstein observed in 1912 that: “Nobody actually questions the powers the Jews exercise in the press. Criticism, in particular, at least as far as the larger towns and their influential newspapers are concerned, seems to be becoming a Jewish monopoly.”

Even Germans opposed to Hitler, like the Hamburg philosopher and women’s rights activist Margarethe Adam, acknowledged the reality of Jewish media control. In a 1929 discussion on the Jewish Question that she conducted with the Jewish historian and sociologist Eva Reichmann-Jungmann, she noted that “The Jew in his very nature is perceived by the Aryan as a different type of human being.” The hostility of many Europeans towards Jews was, she argued, an almost reflexive response to the “teeth gnashing disdain that Jews felt for Christians.” As evidence for her claim, Adam cited the mighty Jewish press, which was “rife with insults and scorn hurled at the great personages of the German past.” She explained that “this press is what causes people to speak repeatedly of ‘Jewish solidarity’ in the worse sense.”[xviii]

Misrepresenting Heinrich von Treitschke

To buttress his “envy” theory of German “anti-Semitism,” Aly cites the 1879 publication of renowned German historian Heinrich von Treitschke’s article “Our Prospects” in the prestigious journal Preussische Jahrbücher. This article was, Aly claims, addressed by the famous historian “to the sons of the rapidly declining artisan and merchant class,” a group that were “fearful for their future.” In his article, Treitschke raised the idea that “in recent times a dangerous spirit of arrogance has been awakened in Jewish circles,” and he demanded that Jews show more “tolerance and humility,” noting that: “The instincts of the masses have recognized in Jews a pressing danger, a deeply troubling source of damage to our new German life.” The most knowledgeable Germans, he proclaimed, were calling out with one voice: “The Jews are our misfortune.”[xix] According to Aly,

Treitschke’s “Our Prospects” polemic characterized Jewish immigrants to Germany from Eastern Europe as “an invasion of young ambitious trouser salesmen” who aimed to see their “children and grandchildren dominate Germany’s financial markets and newspapers.” The nationalist historian pilloried the “scornfulness of the busy hordes of third-rate Semitic talents” and their “obdurate contempt” for Christian Germans, noting how “tightly this swarm kept to itself.” The holder of four professorships in his lifetime, Treitschke worked himself into a veritable frenzy over “the new Jewish nature,” whose tendencies and attributes included “vulgar contempt,” “addition to scorn,” facile cleverness and agility,” “insistent presumption,” and “offensive self-overestimation.” All of these qualities, Treitschke claimed, worked to the detriment of the Christian majority, with its “humble piety” and “old-fashioned, good-humored love of work.” If Jews continued to insist on their separate identity and refused to be integrated into the German (which to Treitschke, meant Protestant) culture of the nation, the historian threatened that “the only answer would be for them to emigrate and found a Jewish state somewhere abroad.”[xx]

Aly takes Treitschke’s article out of its historical and intellectual context, and claims that the hostility toward Jews in Treitschke’s article, which Aly views as completely baseless, was “symptomatic of Germany as a whole,” and was grounded in pathological envy. However, the actual context of Treitschke’s famous article was explicated in Albert Lindemann’s book Esau’s Tears: Modern Anti-Semitism and the Rise of the Jews. Lindemann, noting how this context is “often neglected or ignored in accounts of the period,” observes that the real catalyst for Treitschke adding his voice to complaints about Jews in Germany was the nature of the work of the leading Jewish historian Heinrich Graetz and its enthusiastic reception among German Jews. Lindemann notes:

Although his History of the Jews is still lauded by twentieth-century Jewish historians as one of the great nineteenth-century histories of the Jews, there is little question that the sense of Jewish superiority expressed in it, especially in the eleventh volume, which had first appeared in 1868, was at times narrow and excessive. Indeed compared with it, Treitschke’s history of the Germans may be described as generous in spirit, especially in its treatment of the relationships of Jews and non-Jews, their relative merits and defects.[xxi]

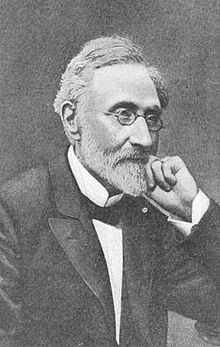

Lindemann points outs that Graetz harbored a “deep contempt for the ancient Greeks and a special derision for Christians in the Middle Ages.” Presaging Freud and the Frankfurt School, Graetz considered contemporary European civilization to be “morally and physically sick.” Lindemann observes that “Graetz had written much that was stunningly offensive to German sensibilities of the time” and that it was hardly surprising that Treitschke responded with “such fury.” Celebrating deceit and guile as highly effective forms of ethnic warfare, Graetz had written that the Jewish writers Boerne and Heine had “renounced Judaism, but only like combatants who, putting on the uniform of the enemy, can all the more easily strike and annihilate him.” Moreover, in his private correspondence, Graetz “expressed his destructive contempt for German values and Christianity more forthrightly.” In a letter to Moses Hess, written in 1868, for instance, he wrote that “we must above all work to shatter Christianity.”

Jewish historian Heinrich Graetz

Jewish historian Heinrich Graetz

On becoming aware of such views, Treitschke angrily observed that “the man shakes with glee every time he can say something downright nasty against the Germans.”[xxii] It was reading Graetz and noting how his brand of history was so highly esteemed by Jews that prompted Treitschke to echo the reactions of many Germans to having their people, culture and religion derided by members of an alien race living in their midst, noting that:

What deadly hatred of the purist and most powerful exponents of German character, from Luther to Goethe and Fichte! And what hollow, offensive self-glorification! Here it is proved with continuous satirical invective that the nation of Kant was really educated to humanity by Jews only, that the language of Lessing and Goethe became sensitive to beauty, spirit and wit only through [the Jews] Boerne and Heine! … And this stubborn contempt for the German goyim is not at all the attitude of a single fanatic.[xxiii]

Graetz found his counterpart in the Weimar Republic in the figure of the Jewish intellectual and journalist Kurt Tucholsky who, using a variety of pseudonyms, “scoffed at the ideals of the German nation: he flung his biting sarcasm and venomous mockery at every religious and national sentiment.” By deliberately excluding the historical and intellectual context of Treitschke’s famous article, Aly perpetuates the false narrative that German hostility towards Jews had absolutely nothing whatever to do with Jewish behavior. This deliberate distortion enables Aly to blithely dismiss Treitschke as an “intellectual agitator” and producer of “anti-Jewish polemics.”

The author also gives the German composer Richard Wagner this kind of shabby treatment, dismissing him as “a paradigmatic example of the way that resentment provoked hatred for Jews among German intellectuals and artists.” As I have previously noted, there is a great deal of validity in the opinions Wagner expressed with regard to the Jewish Question. Aly is unwilling, however to subject Wagner’s writing to any detailed and fair-minded analysis, simply arguing that “none of Wagner’s assorted justifications could disguise the personal economic interest that clearly lay behind his animosity.”[xxiv] According to Aly, anti-Jewish statements are never rational, but always the product of a warped mind, while Jewish critiques of Europeans always have a thoroughly rational basis.

Conclusion

Aly concludes his book by claiming that “Today’s generations of Germans owe a lot to their ancestors’ desires to get ahead in the world. Precisely for that reason, there is no way for them to divorce anti-Semitism from their family histories.” Reinforcing the toxic culture of the Holocaust that is today leading Germany to destruction, he argues that today’s Germans have a moral obligation to come to terms with and atone for “the murderous anti-Semitism of their forefathers.”[xxv]

Despite its many shortcomings (in truth because of them) Why the Germans? Why the Jews? has been lauded by establishment critics. Christopher Browning, writing for the New York Review of Books, described Aly’s book as: “A remarkably fresh look at an old problem. … Aly is one of the most innovative and resourceful scholars working in the field of Holocaust studies. Time and again he has demonstrated an uncanny ability to find hitherto untapped sources, frame insightful questions, and articulate clear if often challenging and controversial arguments.”

The majority of Jewish critics have been similarly admiring. Dagmar Herzog, writing for the New York Times, maintained that “the lavish evidence Aly heaps on — from both self-revealing anti-Semites and acutely prescient Jewish writers — is incredible in its own right and makes for gripping reading.” The Jewish Daily Forward called the book “Consistently absorbing. … A penetrating and provocative study [that] offers shrewd insight into the German mindset over the last two centuries.” Misha Brumlik, writing for the German publication Die Zeit, labelled Aly’s work “Brilliant, passionate, provocative” and according to Michael Blumenthal, once Jimmy Carter’s Treasury secretary and now director of Berlin’s Jewish Museum, claimed that Aly’s “analysis of a profound social malady has made the incomprehensible comprehensible.”[xxvi]

However, for some, Aly’s pathological envy thesis — despite his assiduous efforts to locate the sources of this envy exclusively in the pathologies and malformations of the German mind — is unsatisfactory because it fails to fully capture the truly “evil” nature of the “anti-Semitism” that once pervaded German society. Writing for Commentary magazine the Jewish writer Daniel Johnson dismissed Aly’s underlying message as “a more scholarly version of Hannah Arendt’s ‘banality of evil’ thesis.” According to Johnson, “What made the evil of the Shoah ‘radical’ is that it had no social or economic rationale. Because it had no motive or purpose beyond its own insane internal logic, its cruelty also had no limits, no proportionality, no humanity. It was literally inhuman.” He claims that “envy is too mild a motivation” to account for “truly evil” depths of German Jew-hatred. In his view, “There is something darker, more pathological, more ‘incomprehensible’ going on here.”

While Why the Germans? Why the Jews? flirts with the truth, it is marred by the distortions and omissions I have identified in this review. Competition for access to resources broadly construed to include competition over the construction of culture is undoubtedly a prime cause of intergroup hostility — and it was an important contributing factor in German hostility toward Jews in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. To be charitable, making “envy” the sole causal factor for post-Enlightenment German “anti-Semitism,” is overly simplistic. The sources of German hostility to Jews during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were manifold: Jewish economic competition (exacerbated by Jewish ethnic networking and nepotism), disproportionate Jewish involvement in revolutionary political movements, and Jewish moral and cultural subversion and domination. Ethnic competition takes many forms, and the assertion by Jews of their ethnic interests (economically, politically and culturally) inevitably leads to hostility from those whose interests are compromised. The Germans of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were no exception. Given the ubiquity of “anti-Semitism” throughout history, it should be obvious to everyone that Jews themselves are the carriers and transmitters of “anti-Semitism.”

[i] Norman Cantor, The Jewish Experience: An Illustrated History of Jewish Culture & Society (New York; Castle Press, 1996), 364.

[ii] Adolf Hitler, Hitler’s Second Book: The Unpublished Sequel to Mein Kampf (Enigma Books, 2003), 236-37.

[iii] Jerry Muller, Capitalism and the Jews (NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010), 91.

[iv] Götz Aly, Why the Germans? Why the Jews?: Envy, Race Hatred, and the Prehistory of the Holocaust (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2014), 34.

[v] Ibid., 55.

[vi] Ibid., 34.

[vii] Ibid., 36.

[viii] Ibid., 38.

[ix] Kevin MacDonald, A People That Shall Dwell Alone: Judaism as a Group Evolutionary Strategy with Diaspora People (Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, 2002), 247.

[x] Ibid., 217.

[xi] Götz Aly, Why the Germans?, 31.

[xii] Götz Aly, Why the Germans?, 132.

[xiii] Ibid., 137-38.

[xiv] Kevin MacDonald, Separation and Its Discontents: Toward An Evolutionary Theory of Anti-Semitism (1st Books Library, 2004), 170.

[xv] Watson, The German Genius: Europe’s Third Renaissance, the Second Scientific Revolution and the Twentieth Century (London: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 434.

[xvi] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf ( London, Imperial Collegiate Publishing, 2010), 281; 58.

[xvii] Aly, Why the Germans?, 4.

[xviii] Ibid., 161-62.

[xix] Ibid., 74.

[xx] Ibid., 77.

[xxi] Albert Lindemann, Esau’s Tears: Modern Anti-Semitism and the Rise of the Jews (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 139-40.

[xxii] Ibid., 141.

[xxiii] Ibid., 140.

[xxiv] Ibid., 39.

[xxv] Aly, Why the Germans?, 232.

[xxvi] Ibid., Back cover.