John Friend

John Friend’s Blog

July 25, 2013

Shortly after the Constitutional Convention, when it was up to the states to ratify or reject the newly proposed United States Constitution, the Anti-Federalists were already warning the American people that, once approved and established, a consolidated federal government’s “relentless expansion of arbitrary power was unstoppable, its tendency toward corruption was inevitable, and its appetite for despotism was unquenchable,” according to Joseph J. Ellis in his book American Creation: Triumphs and Tragedies at the Founding of the Republic (pg. 116). Looking back in hindsight, the Anti-Federalists had it exactly right, at least in the case of the United States.

Anti-Federalists, including Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, and others skeptical of a centralized federal government were also raising alarm bells at the prospect of a centralized Bank of the United States shortly after the Constitution was approved and ratified by the states. Alexander Hamilton and the elite banking and financial establishment in America, working on behalf of and in collusion with international financial interests centered around the Jewish banking families in London and other major European capitals, “represented a tiny minority within the overall populace” who “had somehow managed to engineer a hostile takeover of the fledgling American republic and were now poised to consolidate their control to the detriment of all the ordinary citizens, mostly farmers, the true lifeblood of the nation,” writes Ellis (pg. 170).

President Andrew Jackson, amongst others, would later warn the American people of the dangers that monopolistic, speculative financial interests posed to the young United States in the early 1800s. In his 1832 veto of the legislation that would have rechartered the Bank of the United States, President Jackson wrote:

The rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes… Many of our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits, but have besought to make themselves richer by act of Congress.

President Jackson declared to his cabinet “The Bank of the United States is itself a Government,” and warned the American people private corporations sought “power to control the Government and change its character.” He also courageously told his Vice President Martin Van Buren, “The bank is trying to kill me, but I will kill it!” And indeed, President Jackson did just that. However, the international money power seeking to subvert the United States was not defeated.

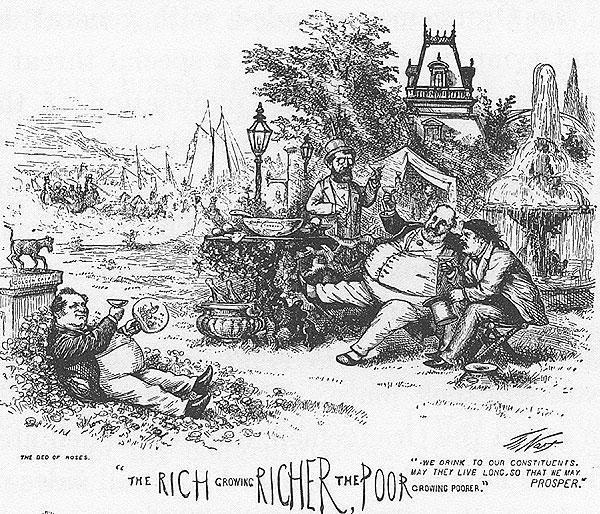

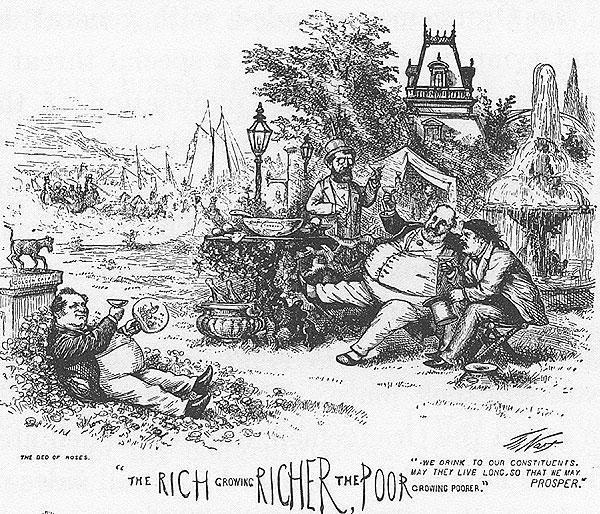

Time and time again, righteous men in American history raised the alarm bells and sought to prevent the subversion and destruction of the nation their ancestors founded. However, the insatiable desire for political and financial control over these United States was unstoppable, and the forces of international speculative financial capitalism came to dominate this country over the course of the 19th century. The destruction of American economic (and political) sovereignty was finally complete with the establishment of the Federal Reserve System in 1913, which centralized the banking and financial apparatus of this nation into the hands of a clique of international plutocrats hell bent on world domination and subjugation. The centralization of a nation’s banking system is a key component of international communism, whose primary goal is the overthrow of Western civilization and all it stands for.

The very concept of a corporation has been transformed and perverted over time. In early American history, states granted private corporations a monopoly on fulfilling a particular public service for a specific period of time. If a road needed to be expanded, for example, and the state was lacking in funds to complete the project, a private corporation would write a charter explaining its purpose (expanding, managing, and maintaining the road expansion) and the state would grant the corporation the privledge of providing an essential public service. Corporations helped build canals, bridges, roads, and other major infrastructure projects, including the extensive railroad system which provided transportation and communication advancements to the American people and private businesses.

But even in this regard, corruption set in, monopolies formed, and the people became oppressed by large financial interests dominating and influencing the state and federal government. Expressing a popular grievance in early America, the editor of New York’s Evening Post William Leggett, wrote:

We cannot pass the bounds of the city without paying tribute to monopoly. Not a road can be opened, not a bridge can be built, not a canal can be dug, but a charter for exclusive privileges must be granted for the purpose… The bargaining and trucking away charted corporation privileges is the whole business of our lawmakers.

The rise of speculative financial capital and large corporations, especially railroad corporations, ushered in an era of unprecedented greed, speculation, corruption, and insider dealings in early American history. Alexis de Tocqueville, the French philosopher and writer who wrote extensively about the unique political and cultural traditions of America, perhaps best expressed the plight of the struggling American frontiersman and farmer. Writing in Democracy in America, Volume Two, de Tocqueville contrasted the “territorial aristocracy” or the traditional elite in European society and the “manufacturing aristocracy” or the financial elite which had arisen in America:

The territorial aristocracy of former ages was either bound by law, or thought itself bound by usage, to come to the relief of its serving-men and to relieve their distresses. But the manufacturing aristocracy of our day first impoverishes and debases the men who serve it and then abandons them to be supported by the charity of the public.

Congressman Hendrick B. Wright of Pennsylvania, a champion of the working class and of the American pioneer, advanced legislation in the late 1870s to help homesteaders – small independent American farmers and ranchers – secure and develop their land without going into massive debt. Congressman Wright’s efforts were defeated by plutocratic financial interests and their minions, who denied the small independent pioneer and farmer – the very men and women who made this country – any sort of financial concessions while they themselves were lavishly awarded government contracts and land grants. Congressman Wright, who once said, “The working men of this land are better entitled to the bounty of Government than aggregated wealth,” responded to the rejection of his legislation with this poignant remark:

Congress can grant railroads money and land, but if it talks of relieving the poor and oppressed, the cry comes, ‘We cannot reward idleness.’

I wonder what Congressman Wright would have said about the criminal bailout of Wall Street in late 2008? Congress can grant Wall Street speculators bailouts as a result of their criminal financial practices, but if it talks of relieving home-owners and oppressed debt-slaves, the cry comes, “We cannot reward idleness.” Has anything really changed in American politics in the past 150 years?

Indeed, government largess and corrupt dealings created corporate bonanzas, especially for railroad corporations, which was the standard operating procedure in America for much of 19th century and even to this day. Railroad, lumber, cattle, and mining interests were essentially handed large land grants and other special privileges and insider-deals by the federal government, while independent American farmers and homesteaders were largely exploited and forced to fend for themselves. After being elected to his first presidential term in 1884, President Grover Cleveland appointed William Andrew Jackson Sparks as land commissioner. Mr. Sparks’ first report to Congress summarized the situation Americans knew all too well:

The widespread belief of the people in this country that the Land Department has been very largely conducted to the advantage of speculation and monopoly, rather than in the public interest I have found supported by developments in every branch of the service.

As former Governor of Pennsylvania Gifford Pinchot explained, “It must be remembered that monopolistic control was infinitely more potent in the West, in those days, than in the East. The big fellow had control of the little fellow to an infinitely greater extent west of the Father of Waters than east of it.” Speculators, monopolists, and plutocrats were taking over America, and those that stood in their way did not stand a chance.

Henry Adams and Charles Francis Adams, Jr. prophetically wrote in the late 1800s:

The belief is common in America that the day is at hand when corporations far greater than the Erie – swaying power such as has never in the world’s history been trusted in the hands of mere private citizens, controlled by single men like Vanderbilt, or by cominations of men like Fisk and Gould… after having created a system of quite but irresistible corruption – will ultimately succeed in directing government itself.

Congressman James B. Weaver, the populist presidential candidate for first the Greenback Party in 1880, then the People’s Party in 1892, described the ails of the American political system which still plague us today when he wrote in 1892, “Public sentiment is not observed. The wealthy and powerful gain a ready hearing, but the plodding, suffering, unorganized complaining multitude are spurned and derided.”

The 19th century truly was a pivotal period of time in American history. It was during this century that the government formed by the Founding Fathers morphed from an instrument which served the American people to one which served private economic interests to the detriment of the average American worker, farmer, craftsman, and independent businessman.

Writing in Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler succinctly explained exactly where America went wrong during the 19th century:

… as economic interests begin to predominate over the racial and cultural instincts in a people or a State, these economic interests unloose the causes that lead to the subjugation and oppression [of those people or State].

Perhaps unknowingly, Adolf Hitler perfectly described the United States of America during the 19th century – and it’s only gotten worse.