Luis Castillo

Daily Stormer

August 30, 2018

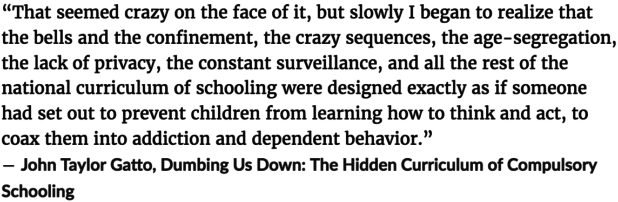

If I have to deal with one more over-educated coward, and listen to one more litany of high culture from one more deeply neurotic, anxious and unhappy bug-person who does not know the basics of being a man, I am going to snap, write a long rant disguised as an insight article, and probably bore the audience and piss off my editor by not writing news.

I am tired of pussies, of lazy degenerates who don’t even know what it means to work, but know what carbon dating is. Seriously, who needs to know this shit?

Face it, reader. You know what carbon dating is, you’ve never used the information, and you never will. How much graffiti like that do you have in your brain? Thirteen years of basic education, just to get to the point where you can go to a university, and maybe finally learn something – but probably not, and just memorize more useless crap.

Knowledge is not a gift.

Knowledge is a burden.

I would have rather been raised by wolves.

Abandoned as a child, Marcos Rodríguez Pantoja survived alone in the wild for 15 years. But living with people proved to be even more difficult.

The first time Marcos Rodríguez Pantoja ever heard voices on the radio, he panicked. “Fuck,” he remembers thinking, “those people have been inside there a long time!” It was 1966, and Rodríguez woke from a nap to the sound of voices. There was nobody else in the room, but the sounds of a conversation were coming from a small wooden box. Rodríguez got out of bed and crept towards the device. When he got closer, he couldn’t see a door, a hatch, or even a small crack in the box’s surface. Nothing. The people were trapped.

Rodríguez had a plan. “Don’t worry, if you all move to one side, I’ll get you out of there,” he yelled at the radio. He ran towards the wall at the other end of the room, the device in his hand. There, breathless and red in the face, he held it high above his head and brought it down hard against the brick wall, in one violent swing. The wood splintered, the speaker popped out of its casing, and the voices fell silent. Rodríguez dropped the radio on to the floor.

When he knelt down to search through the debris, the people weren’t there. He called for them, but they didn’t respond. He searched more frantically, but they still didn’t appear. “I’ve killed them!” Rodríguez bellowed, and ran to his bed, where he hid for the rest of the day.

LOL, WHAT A RETARD AM I RIGHT?

Trying to help people spontaneously, LOL. I can’t even.

Literally, why? What a noob.

Besides, he could get sued.

It’s better to just mind your own business, fellow bugmen. Don’t be like this idiot.

Rodríguez was in his early 20s. He did not have any learning disabilities. Indeed, there was nothing to suggest his intelligence was below average. But he was ignorant of the most basic technology because, between the ages of seven and 19, according to his own testimony, Rodríguez lived alone, far from civilisation, in the Sierra Morena, a deserted mountain range of jagged peaks that stretches across southern Spain.

His story is that he was abandoned as a child of seven, in 1953, and left to fend for himself. Alone in the wild, as he tells it, he was raised by wolves, who protected and sheltered him. With no one to talk to, he lost the use of language, and began to bark, chirp, screech and howl.

Twelve years later, police found him hiding in the mountains, wrapped in a deerskin and with long, matted hair. He tried to flee, but the officers caught him, tied his hands and brought him to the nearest village. Eventually a young priest brought him to the hospital ward of a convent in Madrid, where he stayed for a year and received a remedial education from the nuns.

Was he better off, or did they just throw him into a world of madness, abuse, and misery?

Let’s find out!

It is almost impossible to imagine what it would be like to emerge into adulthood without any of the socialisation that the rest of us unconsciously absorb, via a million imperceptible cues and incidents, as children and teenagers. When he left the convent hospital, adjusting to life among humans brought with it a series of shocks. When he first went to the cinema – to see a Western – he ran out of the theatre because he was terrified of the cowboys galloping toward the camera. The first time he ate in a restaurant, he was surprised he had to pay for his food. One day he went into a church, where an acquaintance had told him God lived. He approached the priest at the altar. “They tell me you’re God,” he said. “They tell me you know everything.”

What an absolute pleb. Everyone knows there’s only one man who knows everything – and that’s Stephen Pinker.

Stephen fucking Pinker, the Jew who thinks he knows everything.

Forget the sutras of the Buddha. That sort of Enlightenment takes too long, and besides, it’s hard. That’s for suckers. There’s a faster way to Enlightenment. You can get it NOW – just read this book, by this fucking Jew.

In the 50 years since he was found in the wilderness, Rodríguez has struggled to get a handle on society’s expectations. He lived in convents, abandoned buildings and hostels all over Spain. He worked odd jobs on construction sites, in bars, nightclubs and hotels; he was robbed and exploited: people took advantage of his unworldliness. Some people did try to help him, but most found him awkward and uncommunicative, and he was largely shunned by society. “For most of my life,” Rodríguez told me, “I had a very bad time among humans”.

…

He found it difficult to look me in the eye, and stared intensely at the ground whenever he spoke. He would make a joke, and laugh at himself, only to lose his confidence almost immediately and retreat behind a sheepish, diffident grin. He was friendly and talkative, but he seemed overly conscious of my reaction to everything he said: if I looked confused, he was visibly discouraged; if I was enthusiastic, he was suddenly excited and energetic. He always seemed to be anticipating his interlocutor’s scorn.

In his company, you cannot help realising that our daily interactions are eased by a stream of invisible signals – a kind of silent language we all understand, which you don’t even notice until it’s absent. “Marcos can first seem unknowable, and difficult to help,” Xosé Santos, one of his friends in the village, had told me. “But once he gets to know you, and you him, he is a very loyal person.”

Rodríguez drew a lighter towards his cigarette and struck. “I’m still amazed by these things,” he chuckled, pointing at a large collection of lighters on a nearby shelf. “If you only knew the lengths I went to to make fire back then.” On the desk behind him is a pile of cuttings from Spanish newspapers, with headlines such as “The Wolfman of the Sierra Morena” and “Living Among Wolves” – mementoes of a bewildering new period in his life.

See? Now he has cigarettes! That, my friends, is progress.

Life status: Improved.

What Rodríguez remembers of his time living wild is that it was “glorious”. When he was found by the police and brought down from the mountains, an untroubled, simple adolescence among animals and birds was cruelly cut short. He had always found it hard to relate to humans, who were baffled by his ignorance and infuriated by his inability to communicate. But now the intensity of their belated fascination was almost as puzzling as their earlier contempt – Rodríguez could never understand what was expected of him.

Rodríguez speaks in a high pitch, oscillating between seriousness and frivolity; a sober tone can turn quickly into a raucous laugh. But he is quiet and solemn when he tries to explain how he suffered at the hands of humans after he returned to society: “I was constantly humiliated. Among people, I learned to hate and to be embarrassed.”

Slowly, he began to hate them.

He told me he was still a child, only six or seven, the first time he encountered wolves. He was looking for shelter from a storm when he stumbled across a den. Not knowing any better, he entered the cave and fell asleep with the pups. The she-wolf had been out hunting, and when she returned with food, she growled and snarled at the boy. He thought the wolf was going to attack him, he says, but she let him take a piece of the meat instead.

Wolves are not the only animals he lived among: he says he made friends with foxes and snakes, and that his enemy was the wild boar. He says he spoke to them all in a mix of grunts, howls and half-remembered words: “I couldn’t tell you what language it was, but I did speak.”

Rodríguez told me this with absolute confidence, as if nothing could have been truer. The fact that I might find it implausible didn’t seem to worry him; it was the one moment when he showed absolutely no concern for my reaction. There was no blushing, no adolescent timidity or raucous, incoherent humour. Indeed, if there was one thing Rodríguez seemed to know for sure – no matter what other people thought – it was that he had lived a better and happier life in the wild. The complexity of his interactions with humans would later grate against the remembered simplicity of his dealings with the animals. “When a person talks, they might say one thing but mean another. Animals don’t do that,” Rodríguez told me.

In early 1965, a park ranger reported to the police that he had seen a man with long hair, dressed in a deerskin, roaming the Sierra Morena. Three mounted officers were sent to search for him. Rodríguez says they found him eating fruit under the shade of a tree deep inside the Sierra.

What a dangerous criminal. Sitting under a tree, eating fruit?

Normal people don’t do that. Normal people wear ties, and work jobs, to pay bills, to buy shit they don’t need. Didn’t this bigot know that he was supposed to live off of corn syrup, deprive himself of sleep, and die of stress?

How absolutely dare he?

He remembers the men dismounted their horses and tried to talk to him, but Rodríguez didn’t know how to respond. He understood their questions, but he hadn’t spoken in 12 years, and no words came. He ran.

The officers caught up with Rodríguez easily. They tied his hands to the saddle of one of their horses and dragged him off the mountain; Rodríguez told me howled as he left the hillside.

Galvez told Gabriel Janer Manila, the anthropologist, that he was at first utterly “unadapted to social norms”, seemingly immune to the cold, and walked with the hunched, bow-legged gait of a monkey. Galvez moved the young man into his family home in Lopera, where he taught him how to dress himself, how to eat correctly, and how to pronounce words. He even arranged football matches so Rodríguez could play with other local children. But Rodríguez resisted. “I would try to run back to the mountains whenever I could,” he told me. “I didn’t feel comfortable among humans.”

You can clearly appreciate the profound damage done to this poor man, by not being forced to socialize with boring little shitbags as a full time job for thirteen years.

While Rodríguez stayed at the convent, he worked on construction sites in and around Madrid. The nuns had hoped this would prepare him for society, but it didn’t help much. “I never had any idea what I was supposed to do,” he told me.

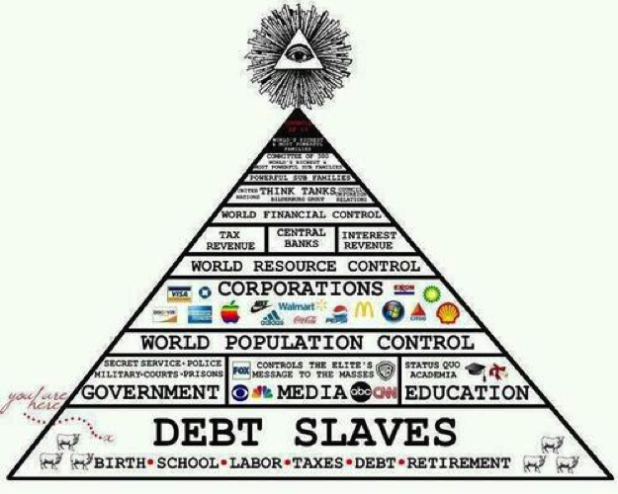

What an idiot. I mean, everyone is born for exactly one reason. It’s this:

At the beginning of 1967, Rodríguez was sent to do military service in Córdoba. He didn’t last long. He fired his gun during a training drill and almost killed a member of his platoon. He was discharged, and returned to the hospital in Madrid. On his return, he met a fellow patient who convinced him to go to the island of Mallorca – which was then turning into a tourist destination for people from all over Europe. There would be lots of work, the man told Rodríguez, and he could finally have some independence.

As soon as they arrived on the island, his travelling companion stole his suitcase and the little money the nuns had given him, and left him stranded in a hostel. The owners, who thought Rodríguez was pulling a scam, called the police. “Luckily the nuns had called ahead to warn the local constabulary of my arrival,” he told me. Instead of being arrested, he was put to work to pay off his debts.

In the following years, he held jobs as an assistant chef, a barman, a bricklayer and a road-sweeper. Because he didn’t understand money very well, his bosses often underpaid him and took advantage of his naivety. “For a while, I was selling marijuana, without knowing. My boss told me it was stomach medicine. People would come to the bar and ask for ‘medicine’, and I’d give it to them.”

I guess he really did have a purpose. Just imagine how much time he wasted, running around in deerskins, eating fruits under trees, when he could have been making good money selling weed.

Or, making his boss good money, whatever.

So much progress.

Juan Font, who worked with Rodríguez on building sites on the island in the 1970s, remembers him as mischievous and funny, but easily exploited. “He was a good person and a hard worker, who we all respected,” he told me over the phone from Mallorca. “I remember he loved to sing; he had a great voice. But it was hard to believe his stories of living in the mountains; they just seemed so unreal.”

Lmao, singing. What a faggot.

You know what makes money? Selling weed.

You know what doesn’t make you money? Singing, like a little faggot.

Roflmao, literally dudes wearing dresses, not making money – wtf are they even saying?

Maybe we can find a doctor of Reason, Science, Humanism and Progress to explain how this guy turned into such a big pussy.

José España, a biologist and specialist in wolf behaviour, who knows Rodríguez, believes his experience was probably comparable. “It’s very possible for humans and wolves to co-exist,” Espana told me. “But do I believe that every time he called the wolves they came to him, as he says? Well, that’s more debatable.”

“Canines coming when called? Lol no I don’t believe that.” – Spic Expert Guy

Certainly, the wolves would have come to Rodríguez when he had food. “Marcos is what I would call a periphery wolf – tolerated by the alpha, and by the rest of the pack because he posed no threat,” España said. “How he chose to interpret these interactions, however, is most likely a case of selective memory.”

Janer says the young boy would have projected his social needs on to the animals and imagined relationships with them. “When Pantoja says the fox laughed at him, or that he had to tell off the snake, he gives us a version of the true reality, what he believes happened – or how, at least, he explained the reality to himself,” Janer told me. “Marcos’s mind was desperate for social acceptance,” he told me, “so instead of understanding the animals’ presence as incentivised by the food, he thought they were trying to make friends.”

Yes – unlike humans, who make friends for totally enlightened, selfless reasons, and not trying to get food or some other material or social benefit, especially these days.

Thanks, spic expert guy!

“I’m a biologist, and basically, fuck you and the 15 years you lived with wolves.” – Spic Expert Guy

Rodríguez left Mallorca in the 80s and moved to the south of Spain, where he worked in a series of jobs – “anything that didn’t involve reading or writing,” he said. He was at his local bar almost every day, getting drunk and playing the fruit machine. “This was the time that Marcos’s life passed in a blur of alcohol and odd jobs,” Gerardo Olivares told me.

Ah, yes.

Finally, a heartwarming end to a heartwarming tale – the man is finally liberated from the corruption of the natural world, and returned to his original state of Innocence and Grace – through Alcohol.

Man, redeemed.

Rodríguez could not understand how his story could be met with complete indifference for decades, only to make him famous 40 years after Janer first wrote about it. “Especially when I hadn’t changed,” he said. To him, all this newly discovered adulation seemed just another hurtful, incomprehensible quirk of the human mind.

From the window of Rodríguez’s house, I saw that the morning frost had lifted, and the sun bobbed above. The house had no central heating, and the crisp February air collected in dense clouds around his nose and mouth as he spoke. “You know, at first they didn’t want to listen to a word of what I was saying. Now, they can’t stop listening. What is it they actually want?”

Lol, we want entertainment, you stupid wolf retard.

Okay. I’m done being cute.

Reader, I want you to take a good, long look in the mirror. Except, you probably don’t have a mirror on hand, and if you were to get up and go near one, you couldn’t keep reading the article.

So, fine, whatever. I assume you have a relatively new computer with a camera on it, watching you all the time, and you don’t even have the good sense to tape it, so I want you to click on the menu in the bottom left, and type in: Camera, and open it, or open it with this link if you really cannot figure out how to look at yourself through your PC camera.

Mobile users – I don’t know. Take a selfie. Whatever.

Take a long, hard look at yourself in the camera. Answer the wolf-man’s question.

What is it you actually want?

What is your time even going into?

Is this really necessary, in the hunter-gatherer sense of the word?

If it is, then, I guess you must be really poor – which means that your use of your own time actually has some inherent meaning to it, so I guess you’re lucky, if necessity has freed you of purposelessness.

Otherwise, though – tell me, honestly.

Do you not spend most of your waking hours chasing after things that you do not need?

Was this wolf-man not happier, without even a percentage of the things you burden yourself with?

Why, then, do you not shrug off these burdens?

Am I telling you to just say “fuck it” and go full primitive? I don’t know. You figure out your own business.

Whatever you do, you should give up the things you don’t need.

You need some goal to your existence, though, beyond just surviving another day.

The only reason I have not gone full primitive, is because I have been burdened with Knowledge. I know what I have to do with my life, and I couldn’t forget it if I tried – and I’ve tried. It always came back to bug me.

So, that’s the way things are, and the way things should be.

I would be much better off sitting under a tree with a full stomach and an empty mind.

This present world is a rebellion against the natural Order. It is less than the natural world, and we are made less by living it.

This is not “progress.”

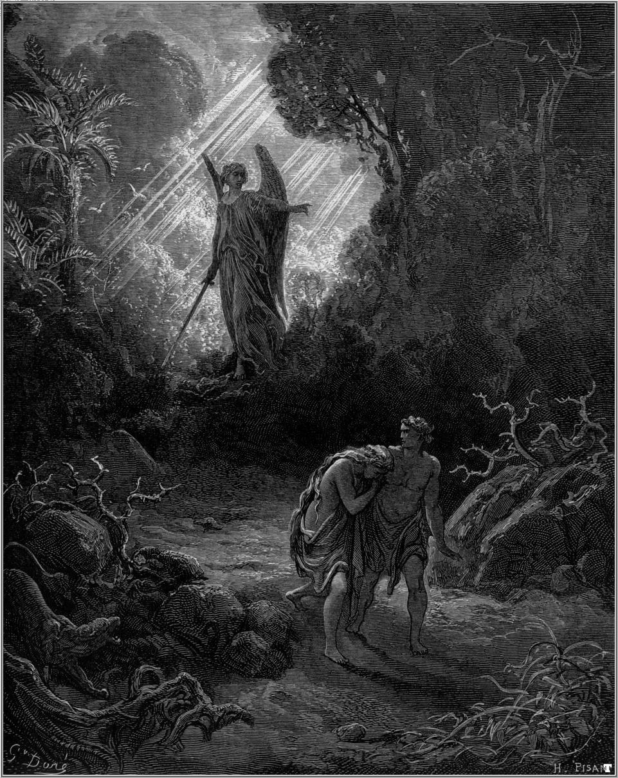

This is Exile.