Diversity Macht Frei

February 20, 2018

If you read the New Testament you will come across St. Paul’s letters to some of the earliest Christian communities such as the Galatians or Ephesians. Most of those places were once part of the Byzantine empire, the eastern extension of the Roman empire, which was the principal Christian power of its time. Now they are almost all part of Turkey. How did the Turks (Ottomans) make such inroads into Christian territory? Part of the answer is that the Christians were betrayed from within.

Even when the Byzantines were unable to deploy effective field armies, they were often secure within massively fortified cities. The Byzantine capital, Constantinople, named after its founder Constantine, the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity, is a case in point. First put under siege by Muslim armies in 674, it nonetheless held on for almost another 800 years, until 1453. When the end came for Constantinople, as for so many other great Christian cities, it was because the defenders had been betrayed from within by Jews.

Here is an extract from the book “The Jews of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic” by the Jewish historian Stanford J. Shaw.

The Jews of Bursa, Byzantine administrative center of northwestern Anatolia, actively helped Osman’s son Orhan (1324-59) capture the city in 1324.

…

The Ottoman conquests of Gallipoli (1354) by Orhan’s son Suleyman Pasha, of Ankara (1360) in central Anatolia and of the Byzantine administrative capital of Southeastern Europe, Adrianople, in 1363 by Murad I, also were accomplished with support from the small and impoverished Jewish communities which had lived there under Byzantine persecution. Just as at Bursa, so also at Adrianople, now called Edirne, to restore it economically and make it into the capital of the Ottomans’ European possessions as quickly as possible, the Turkish conquerors repopulated it with large numbers of Jews resettled from the newly conquered lands in Bosnia and Serbia as well as with Ashkenazi refugees from Hungary, southern Germany, Italy, France, Poland and Russia, providing them with substantial tax and other concessions.

…

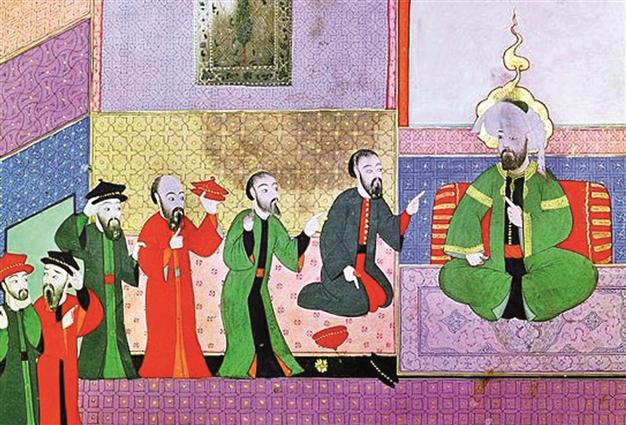

When the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II Fatih (The Conqueror) captured Constantinople and brought the Byzantine Empire finally to an inglorious end in 1453, his armies broke into the city through one of the Jewish quarters and with the assistance of the local Jewish population who, as at Bursa and Edirne, were overjoyed at the opportunity to throw off their Greek oppressors. So also at Buda and Pest in 1526, on the island of Rhodes in 1522, at Belgrade (1526), in Azerbaijan (1534), Iraq and Iran (1534-35, 1638). Yemen (1628) and elsewhere, Jews welcomed the conquering forces of Suleyman the Magnificent, and in each case they were rewarded with tax exemptions, concessions for trade and exploitation of minerals, repair or expansion of old synagogues, and even free houses and shops to meet the needs of the increasing Jewish populations.

Source: “The Jews of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic” by Stanford J. Shaw. (link)

Of course he justifies the Jewish betrayal by claiming the Jews were “persecuted” under the Christians. This is a constant of Jewish historiography. On the rare occasion that a Jewish historian deigns to acknowledge the fact of Jews harming a non-Jewish people at all, it is invariably justified with the claim that the people so betrayed were “anti-Semitic”. But in that case why were the Jews there at all? If the Jews weren’t satisfied with their conditions of life, why didn’t they just leave? And the argument works both ways. With a track record of treacherous conduct stretching back thousands of years, is it not reasonable to be “prejudiced” against such a volatile Middle-Eastern minority who might betray you to a foreign aggressor at a critical moment?