Mark Deavin

The Legacy of Dr. William Pierce

August 29, 2014

After fifty years of being confined to the Orwellian memory hole created by the Jews as part of their European “denazification” process, the work of the Norwegian author Knut Hamsun — who died in 1952 — is reemerging to take its place among the greatest European literature of the twentieth century. All of his major novels have undergone English-language reprints during the last two years, and even in his native Norway, where his post-1945 ostracism has been most severe, he is finally receiving a long-overdue recognition. Of course, one debilitating question still remains for the great and good of the European liberal intelligentsia, ever eager to jump to Jewish sensitivities. As Hamsun’s English biographer Robert Ferguson gloomily asked himself in 1987: “Could the sensitive, dreaming genius who had created beautiful love stories … really have been a Nazi?” Unfortunately for the faint hearts of these weak-kneed scribblers, the answer is a resounding “yes.” Not only was Knut Hamsun a dedicated supporter of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist New Order in Europe, but his best writings — many written at the tail end of the nineteenth century — flow with the essence of the National Socialist spirit and life philosophy.

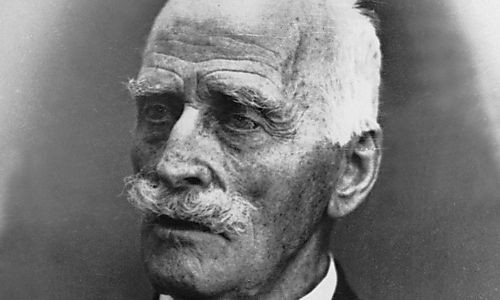

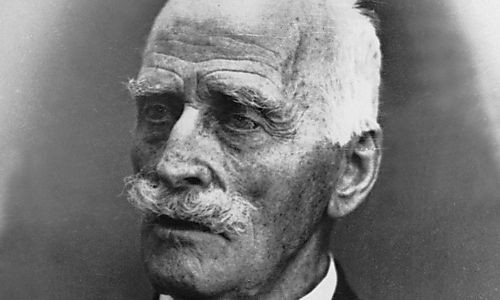

Born Knud Pederson on August 4, 1859, Hamsun spent his early childhood in the far north of Norway, in the small town of Hamaroy. He later described this time as one of idyllic bliss where he and the other children lived in close harmony with the animals on the farm, and where they felt an indescribable oneness with Nature and the cosmos around and above them. Hamsun developed an early obsession to become a writer and showed a fanatical courage and endurance in pursuing his dream against tremendous obstacles. He was convinced of his own artistic awareness and sensitivity, and was imbued with a certainty that in attempting to achieve unprecedented levels of creativity and consciousness, he was acting in accordance with the higher purpose of Nature.

In January 1882 Hamsun’s Faustian quest of self-discovery took him on the first of several trips to America. He was described by a friend at the time as “tall, broad, lithe with the springing step of a panther and with muscles of steel. His yellow hair … drooped down upon his … clear-cut classical features.”

These experiences consolidated in Hamsun a sense of racial identity as the bedrock of his perceived artistic and spiritual mission. A visit to an Indian encampment confirmed his belief in the inherent differences of the races and of the need to keep them separate, but he was perceptive enough to recognize that America carried the seeds of racial chaos and condemned the fact that cohabitation with Blacks was being forced upon American Whites.

Writing in his book On the Cultural Life of Modern America, published in March 1889, Hamsun warned that such a situation gave rise to the nightmare prospect of a “mulatto stud farm” being created in America. In his view, this had to be prevented at all costs with the repatriation of the “black half-apes” back to Africa being essential to secure America’s future (cited in Robert Ferguson, Enigma: The Life of Knut Hamsun, London, 1987, p.105). Hamsun also developed an early awareness of the Jewish problem, believing that “anti-Semitism” inevitably existed in all lands where there were Jews — following Semitism “as the effect follows the cause.” He also believed that the departure of the Jews from Europe and the White world was essential “so that the White races would avoid further mixture of the blood” (from Hamsun’s 1925 article in Mikal Sylten’s nationalist magazine Nationalt Tidsskrift). His experiences in America also strengthened Hamsun’s antipathy to the so called “freedom” of democracy, which he realized merely leveled all higher things down to the lowest level and made financial materialism into the highest morality. Greatly influenced by the works of Friedrich Nietzsche, Hamsun saw himself as part of the vanguard of a European spiritual aristocracy which would reject these false values and search out Nature’s hidden secrets — developing a higher morality and value system based on organic, natural law. In an essay entitled “From the Unconscious Life of the Mind,” published in 1890, Hamsun laid out his belief:

An increasing number of people who lead mental lives of great intensity, people who are sensitive by nature, notice the steadily more frequent appearance in them of mental states of great strangeness … a wordless and irrational feeling of ecstasy; or a breath of psychic pain; a sense of being spoken to from afar, from the sky or the sea; an agonizingly developed sense of hearing which can cause one to wince at the murmuring of unseen atoms; an irrational staring into the heart of some closed kingdom suddenly and briefly revealed.

Hamsun expounded this philosophy in his first great novel Hunger, which attempted to show how the known territory of human consciousness could be expanded to achieve higher forms of creativity, and how through such a process the values of a society which Hamsun believed was increasingly sick and distorted could be redefined for the better. This theme was continued in his next book, Mysteries, and again in Pan, published in 1894, which was based upon Hamsun’s own feeling of pantheistic identification with the cosmos and his conviction that the survival of Western man depended upon his re-establishing his ties with Nature and leading a more organic and wholesome way of life.In 1911 Hamsun moved back to Hamaroy with his wife and bought a farm. A strong believer in the family and racial upbreeding, he was sickened by the hypocrisy and twisted morality of a modern Western society which tolerated and encouraged abortion and the abandonment of healthy children, while protecting and prolonging the existence of the criminal, crippled, and insane. He actively campaigned for the state funding of children’s homes that could take in and look after unwanted children and freely admitted that he was motivated by a higher morality, which aimed to “clear away the lives which are hopeless for the benefit of those lives which might be of value.”

In 1916 Hamsun began work on what became his greatest and most idealistic novel, Growth of the Soil, which won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1921. It painted Hamsun’s ideal of a solid, farm-based culture, where human values, instead of being fixed upon transitory artificialities which modern society had deemed fashionable, would be based upon the fixed wheel of the seasons in the safekeeping of an inviolable eternity where man and Nature existed in harmony:

They had the good fortune at Sellanraa that every spring and autumn they could see the grey geese sailing in fleets above that wilderness, and hear their chatter up in the air — delirious talk it was. And as if the world stood still for a moment, till the train of them had passed. And the human souls beneath, did they not feel a weakness gliding through them now? They went to their work again, but drawing breath first, for something had spoken to them, something from beyond.

Growth of the Soil reflected Hamsun’s belief that only when Western man fully accepted that he was intimately bound up with Nature’s eternal law would he be able to fulfill himself and stride towards a higher level of existence. At the root of this, Hamsun made clear, was the need to place the procreation of the race back at the center of his existence:

Generation to generation, breeding ever anew, and when you die the new stock goes on. That’s the meaning of eternal life.

The main character in the book reflected Hamsun’s faith in the coming man of Europe: a Nietzschean superman embodying the best racial type who, acting in accordance with Nature’s higher purpose, would lead the race to unprecedented levels of greatness. In Hamsun’s vision he was described thus:

A tiller of the ground, body and soul; a worker on the land without respite. A ghost risen out of the past to point to the future; a man from the earliest days of cultivation, a settler in the wilds, nine hundred years old, and withal, a man of the day.

Hamsun’s philosophy echoed Nietzsche’s belief that “from the future come winds with secret beat of wings and to sensitive ears comes good news” (cited in Alfred Rosenberg, The Myth of the Twentieth Century). And for Hamsun the “good news” of his lifetime was the rise of National Socialism in Germany under Adolf Hitler, whom he saw as the embodiment of the coming European man and a reflection of the spiritual striving of the “Germanic soul.”The leaders of the new movement in Germany were also aware of the essential National Socialist spirit and world view which underlay Hamsun’s work, and he was much lauded, particularly by Joseph Goebbels and Alfred Rosenberg. Rosenberg paid tribute to Hamsun in his The Myth of the Twentieth Century, published in 1930, declaring that through a mysterious natural insight Knut Hamsun was able to describe the laws of the universe and of the Nordic soul like no other living artist. Growth of the Soil, he declared, was “the great present-day epic of the Nordic will in its eternal, primordial form.”

Hamsun visited Germany on several occasions during the 1930s, accompanied by his equally enthusiastic wife, and was well impressed by what he saw. In 1934 he was awarded the prestigious Goethe Medal for his writings, but he handed back the 10,000 marks prize money as a gesture of friendship and as a contribution to the National Socialist process of social reconstruction. He developed close ties with the German-based Nordic Society, which promoted the Pan-Germanic ideal, and in January 1935 he sent a letter to its magazine supporting the return of the Saarland to Germany. He always received birthday greetings from Rosenberg and Goebbels, and on the occasion of his 80th birthday from Hitler himself.

Like Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, Hamsun was not content merely to philosophize in an ivory tower; he was a man of the day, who, despite his age, strove to make his ideal into a reality and present it to his own people. Along with his entire family he became actively and publicly involved with Norway’s growing National Socialist movement in the form of Vidkun Quisling’s Nasjonal Samling (National Assembly). This had been founded in May 1933, and Hamsun willingly issued public endorsements and wrote articles for its magazine, promoting the National Socialist philosophy of life and condemning the anti-German propaganda that was being disseminated in Norway and throughout Europe. This, he pointed out, was inspired by the Jewish press and politicians of England and France who were determined to encircle Germany and bring about a European war to destroy Hitler and his idea.

With the outbreak of war Hamsun persistently warned against the Allied attempts to compromise Norwegian neutrality, and on April 2, 1940 — only a week before Hitler dramatically forestalled the Allied invasion of Norway — Hamsun wrote an article in the Nasjonal Samling newspaper calling for German protection of Norwegian neutrality against Anglo-Soviet designs. Hamsun was quick to point out in a further series of articles soon afterward, moreover, that it was no coincidence that C.J. Hambro, the president of the Norwegian Storting, who had conspired to push Norway into Allied hands and had then fled to Sweden, was a Jew. In his longest wartime article, which appeared in the Axis periodicalBerlin-Tokyo-Rome in February 1942, he also identified Roosevelt as being in the pay of the Jews and the dominant figure in America’s war for gold and Jewish power. Declaring his belief in the greatness of Adolf Hitler, Hamsun defiantly declared: “Europe does not want either the Jews or their gold.”

Hamsun’s loyalty to the National Socialist New Order in Europe was well appreciated in Berlin, and in May 1943 Hamsun and his wife were invited to visit Joseph Goebbels, a devoted fan of the writer. Both men were deeply moved by the meeting, and Hamsun was so affected that he sent Goebbels the medal which he had received for winning the Nobel Prize for idealistic literature in 1920, writing that he knew of no statesman who had so idealistically written and preached the cause of Europe. Goebbels in return considered the meeting to have been one of the most precious encounters of his life and wrote touchingly in his diary: “May fate permit the great poet to live to see us win victory! If anybody deserved it because of a high-minded espousal of our cause even under the most difficult circumstances, it is he.” The following month Hamsun spoke at a conference in Vienna organized to protest against the destruction of European cultural treasures by the sadistic Allied terror-bombing raids. He praised Hitler as a crusader and a reformer who would create a new age and a new life. Then, three days later, on June 26, 1943, his loyalty was rewarded with a personal and highly emotional meeting with Hitler at the Berghof. As he left, the 84 year-old Hamsun told an adjutant to pass on one last message to his Leader: “Tell Adolf Hitler: we believe in you.”

Hamsun never deviated from promoting the cause of National Socialist Europe, paying high-profile visits to Panzer divisions and German U-boats, writing articles and making speeches. Even when the war was clearly lost, and others found it expedient to keep silence or renounce their past allegiances, he remained loyal without regard to his personal safety. This was brought home most clearly after the official announcement of Hitler’s death, when, with the German Army in Norway packing up and preparing to leave, Hamsun wrote a necrology for Hitler which was published in a leading newspaper:

Adolf Hitler: I am not worthy to speak his name out loud. Nor do his life and his deeds warrant any kind of sentimental discussion. He was a warrior, a warrior for mankind, and a prophet of the gospel for all nations. He was a reforming nature of the highest order, and his fate was to arise in a time of unparalleled barbarism, which finally felled him. Thus might the average western European regard Adolf Hitler. We, his closest supporters, now bow our heads at his death.

This was a tremendously brave thing for Hamsun to do, as the following day the war in Norway was over and Quisling was arrested. Membership in Quisling’s movement after April 8, 1940, had been made a criminal offense retroactively by the new Norwegian government, and the mass roundups of around 40,000 Nasjonal Samling members now began in earnest. Hamsun’s sons Tore and Arild were picked up within a week, and on May 26 Hamsun and his wife were placed under house arrest. Committed to hospital because of his failing health, Hamsun was subject to months of interrogation designed to wear down and confuse him. As with Ezra Pound in the United States, the aim was to bring about a situation where Hamsun’s sanity could be questioned: a much easier option for the Norwegian authorities than the public prosecution of an 85-year-old literary legend.

Unfortunately for them, Hamsun refused to crack and was more than a match for his interrogators. So, while his wife was handed a vicious three-year hard-labor sentence for her National Socialist activities, and his son Arild got four years for having the temerity to volunteer to fight Bolshevism on the Eastern Front, Hamsun received a 500,000-kroner fine and the censorship of his books. Even this did not stop him, however, and he continued to write, regretting nothing and making no apologies. Not until 1952, in his 92nd year, did he pass away, leaving us a wonderful legacy with which to carry on the fight which he so bravely fought to the end.