The Right Stuff

July 8, 2016

https://soundcloud.com/tharru-635500471/locke-two-treatises-of-government

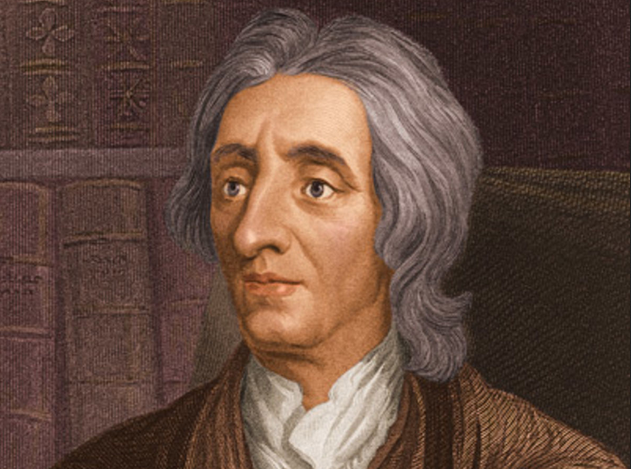

This week the KulturKampf panel is joined by Rebel Yell host, Musonius Rufus to discuss the political and philosophical aspects and implications of John Locke’s infamous Two Treatises of Government.

Intro: Henry Purcell Rondeau from Abdelazer

Outro: Elgar Nimrod

Minutes from the Guard tower By Gaius Tacitus

Locke

Two Treatises of Government

Of the State of Nature:

It is a ‘State of perfect Freedom’ and a ‘State of perfect Equality’. Man’s actions are only bound by the ‘Law of Nature’.

Commentary: As Locke describes it there is some overlap and similarity here with the description Hobbes, and later Rousseau, give for the State of Nature – though there are some subtle differences.

‘Nature hath made men so equal, in the faculties of body, and mind; as that though there be found one man sometimes manifestly stronger in body, or of quicker mind then another; yet when all is reckoned together, the difference between man, and man, is not so considerable, as that one man can thereupon claim to himself any benefit, to which another may not pretend, as well as he. For as to the strength of body, the weakest has strength enough to kill the strongest, either by secret machination, or by confederacy with others, that are in the same danger with himself.’ Ch. XIII Leviathan

SPF – ‘To order their actions, and dispose of their possessions, and persons as they think fit… without asking leave, or depending upon the Will of any other Man’.

SPE – ‘All power and jurisdiction is reciprocal, no one having more than another: there being nothing more evident, than that creatures of the same species and rank promiscuously born to all the same advantages of Nature, and the use of the same faculties should also be equal one amongst another without Subordination or Subjection, unless the Lord and Master of them all, should by any manifest declaration of his will set one above another, and conger on him by an evident and clear appointment an undoubted right to dominion and sovereignty’.

Law of Nature: ‘The State of Nature has a Law of Nature to govern it, which obliges every one: And Reason, which is that Law, teaches all Mankind, who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his Life, Health, Liberty, or Possessions. For Men being all the Workmanship of one Omnipotent, and infinitely wise Maker; All the Servants of one Sovereign Master, sent into the World by his order and about his business, they are his Property, whose Workmanship they are, made to last during his, not one another’s Pleasure’.

Commentary: Locke calls the State of Nature a ‘State of Liberty’ but not a ‘State of License’. This is a subtle echoing of Hobbes – again with a marked difference. This being that in Hobbes’ Nature the concept of license does not exist; men are free to choose the best means of their own preservation and contentment limited only by their capability in achieving these ends. Locke departs from Hobbes and stipulates a further requisite burden upon men in the State of Nature by claiming though they may, or are able to, do whichever thing their will desires they are not granted unlimited authority to do so. This limitation is then further explained in the above quoted section.

We may not subordinate one another under our own authority given we are all the works of God which it is he alone who possesses such power. We are bound by custodianship as objects of God’s creation to maintain our own lives and cannot give them up willfully i.e. we do not own ourselves in the same way we own the acorns which are our property by right of our labor we invest into harvesting them. Similarly, it is God’s labor Locke claims precludes us from owning ourselves as we own the acorns. When our lives are not in any state of competition Locke claims we ought to ‘preserve the rest of Mankind’. The only acceptable instance where one may ‘take or impair’ the life of another is when another man has sought to breach the Law of Nature and impede upon another’s ‘Life, the Liberty, Health, Limb, or Goods of another’.

In the State of Perfect Equality crimes are punished in accordance with their degree as it relates to the violation of the Law of Nature such that punishment serves to enhance ‘reparations and restraint’. Punishment is not based on one’s emotional desires or ‘boundless extravagancy of his own Will’.

The normative claim to punishment rests in the inference that one who becomes a criminal has signaled to others he no longer lives by the Law of Nature but another ‘Rule’ not within the realm of reason.

Locke on ‘alien’ criminals:

Because a foreigner has not consented to the laws of the nation no Prince authorized as such may ‘put to death or punish an Alien, for any Crime he commits in their Country’. (Section 10 – 11)

Inconveniences of State of Nature and Law of Nature:

Because the Law of Nature grants ‘Executive Power’ to all in the State of Nature to wield those powers and privileges also granted by the Law of Nature the State of Nature will be ‘nothing but Confusion and Disorder’ according to Locke. This following from God Locke claims it also follows from God that Government be the solution granted by God to Man in order ‘to restrain the partiality and violence of man’.

Commentary: This is where Locke musters his attack against monarchism and monarchies. Because the State of Nature is chaotic and disorderly due to every man acting as his own judge and executioner in all cases then government, if it is to be a remedy to this State, must not replicate the State of Nature by manner of common consensus and consent under one man who may judge all men in the same way men judge each other in the State of Nature.

Locke claims, in response to the question as to where such men in a State of Nature appear who are not bound to submit to the unjust will of another, all such governments, rulers, and princes have been in ‘a State of Nature’. For Locke it seems what distinguishes a community extricated from the State of Nature requires ‘one Body Politik’ which has come ‘together mutually to enter into one Community’. Further, he remarks “‘tis not every Compact that puts an end to the State of Nature between Men”.

If this is the case then Locke must account for the reasoned supposition that groups of common interests within a body politik may (and do) come together under consensus of mutual ends to function as an organic singular entity which, to take a page from Hobbes’ Leviathan, when all are reckoned together, the difference between body politik and monarch is not so considerable.

The thrust of this objection highlights the lack of developed thought in Locke’s arguments since he cannot respond simply with the predictable ‘they have then devolved back into the State of Nature’ for just as a community may consent to a monarch and be under tyranny soon after so too is this possible under a body politik which has forsaken their appointed duty within the community. Further, that which may be achieved by a body politik is equally achievable under a monarch given the faults of government lie not in theory but rather in man and so to stipulate utility as the guiding force behind Locke’s preference for a body politik over a monarchy this stipulation does not motivate in challenging the further claim that if utility be one’s chosen argument then just as Locke claims ‘Much better it is in the state of nature wherein Men are not bound to submit to the unjust will of another’ one may also equally claim how much better it is to be guaranteed not to be bound to the unjust will of all members of one’s community under the watchful authority of one prince as opposed to the increased risk of being subjected to the unjust will of a body politik comprised of factional groups competing for power amongst one another who use the people as their personal bludgeon against their opposition.

That is, only a madman would consider it preferable to be under attack from, or at war with, five common enemies as opposed to one. In terms of probability if we assign some probability N to the likelihood a Prince may impose tyranny then, assuming the above imperceptible distinction between body politic and monarchy holds, in a body politik N grows as the number of factions within the body politik grow e.g. if Monarchy is calculated to bear a thirty-five percent (35%) chance of devolving into tyranny then among a body politik composed of six competing groups who function against one another as an organic whole indistinguishable from a monarch – micro-monarchies – then the probability of coming under some form of tyranny has now increased two hundred and ten percent (210%).

State of War:

A State of War between two Men consists in a carefully thought out action. Doing so opens whoever makes the declaration up to have his own life rightfully taken but the other. ‘It being reasonable I should have a Right to destroy that which threatens me with Destruction’. Those who violate the law of reason operate only under ‘force and violence’ and so may be treated as ‘beasts’.

Commentary: Locke uses the above characterization of the State of War as a preface for justifying absolute power (monarchy) as that declaration of war by a monarch against our own lives as he characterizes it, ‘He who would get me into his Power without my consent, would use me as he pleased, when he had got me there, and destroy me too when he had a fancy to it: for nobody can desire to have me in his Absolute Power, unless it be to compel me by force to that, which is against the Right of my Freedom, i.e. make me a slave’. Locke desires us to believe with him that anyone who seeks to take away our liberty would also seek to ‘take away everything else’

This doesn’t necessarily follow however, and if we’re to assume the mantle of reason then it is reasonable to surmise one who has consulted reason to see the folly in reducing men to having only their lives to lose and thus being more amenable to open and armed revolt. Men are much more likely to accept a little tyranny for a lot. If we are told by our monarch to wear seatbelts or face some punishment this is certainly a revocation of our liberty but it by no means convinces anyone that the monarch will be seizing our homes very soon thereafter. Likewise, such a seizure is again just as easily acted upon by a body politik as it is under a monarch.

The State of War can be found wherever there are no Authorities or Earthly powers ‘from which relief can be had by appeal’. The lack of a common judge granted authority by the consent of the commons puts men back into the State of Nature and unjust war (‘Force without Right’) puts men into a State of War against one another even in cases where there is a common judge.

On Slavery:

Natural liberty is essentially to be autonomous to one’s own will and not under another’s.

Liberty of Men in Society is to be subject to legislative authority derived from the consent of those in the respective commonwealth. Freedom of man under government is, ‘to have a standing rule to live by, common to everyone of that Society, and made by the Legislative Power erected in it; A Liberty to follow my own Will in all things, where the Rule prescribes not; and not to be subject to the inconstant, uncertain, unknown, Arbitrary Will of another man’.

Men may not enslave themselves when they do not have control over their own life neither by contract or consent. Slavery is the end result of a justified war where if you declare war justly against another man and win you are allowed to stay his execution and use him instead as slave labor. However, the captive may, when he finds his own servitude a greater pain than his death, move towards the realization of this desired death.

Section 23-24 (Slavery):

“This freedom from Absolute, Arbitrary Power, is so necessary to, and closely joyned with a Man’s Preservation, that he cannot part with it, but by what forfeits his Preservation and Life together”.

One might surmise God’s power is both Absolute and Arbitrary for what God so chooses is not derived from anything other than his own will and desire. Thus, if this is what constitutes ‘Arbitrary’ in the sense of men in the State of Nature where coming under tyranny is a transition into a State of War then one is under the tyranny of God insofar as the comparison holds. Unless there is a sufficient explanation as to why this comparison is not equivalent between Man and God then this cannot be anything other than the proper conclusion we make.

If this is the case then there becomes an incoherence, or more graciously a mild confusion on Locke’s part, when it comes to one man subservient to another. The question Locke must answer is to what reason can we point which denies the possibility of God’s will manifest itself through this man over and against the will of the other man? It would seem heretical to presuppose that we ought not favor in the positive the possibility of such a condition since to do otherwise would arrogantly deny God such a will and desire.

Further, if we are to suppose otherwise on the basis of God’s beneficence then to what reason do we offer as evidence in favor of this supposition which could not just as readily be offered against it in favor of a Malevolent god? Certainly if we may surmise against ‘he who, who would take away my Liberty, would not when he had me in his Power, take away everything else’ then, Mankind being made in God’s image, surely must give us warrant to conclude of God the same condition as man.

All objections to the contrary render both discourses on the nature of God and likewise the nature of man merely subjective conjecture aimed at fitting the agenda and desires of those men’s intellect under the pressure of reconciliation.

Property:

From the State of Nature there are things which we may remove and when we invest our own labor, which does not exist in the State of Nature until we introduce it, the act of laboring to procure these things makes them our property.

Because each Man’s labor exists within their own body as potential Labor when it becomes kinetic Labor it originates from the Man and never severs this link to him. By ‘annexing’ some things from the commons we attach a part of our own selves to this common thing which existed in the State of Nature and so now it is tied to the Man who removes it through labor and cannot be said to be anyone else’s by right.

This is not license to hoard or take more than one’s share from the commons. Taking more than one can consume results in spoil and Locke appeals to God putting goods on Earth to be enjoyed not spoiled.

On the subject of land Locke claims the seizure of land and making it one’s property through their labor does not reduce anything in the commons but instead increases it. This is due to the cultivation of land by Man as opposed to the natural production of goods in nature is much greater. As with taking out of the commons Men ought not take more land than they can cultivate because any product that spoils also ‘offends against the common Law of Nature, and was liable to be punished’.

Section 91 (Political Society):

“For he being supposed to have all, both Legislative and Executive Power in himself alone, there is no Judge to be found, no Appeal lies open to anyone, who may fairly, and indifferently, and with Authority decide, and from whose decision relief and redress may be expected of any Injury or Inconveniency, that may be suffered from the Prince or his Order: So that such a Man, however intitled, Czar or Grand Signior, or how you please, is as much in the state of Nature, with al under his Dominion, as he is with the rest of Mankind. For wherever any two Men are, who have no standing Rule, and common Judge to Appeal to on Earth for the determination of Controversies or Right betwixt them, there they are still in the state of Nature, and under all the inconveniences of it, with only this woeful difference to the Subject, or rather Slave of an Absolute Prince: That whereas, in the ordinary State of Nature, he has a liberty to judge of his Right, and according to the best of his Power, to maintain it; no whenever his Property is invade by the Will and Order of his Monarch, he has not only no Appeal, as those in society ought to have ,but as if he were degraded from the common state of Rational Creatures, is denied a liberty of, or to defend his Right, and so is exposed to all the Misery and Inconveniencies that a Man can fear from one, who being in the unrestrained state of Nature, is yet corrupted with Flattery, and Armed with Power.”

That monarchy is inconsistent with civil society:

Under a monarchy there is no judge for men under the dominion of the monarch to appeal against the actions of the monarch. The absence of this renders the monarch and his dominated subjects in the state of nature still against the idea of forming communities to exit the state of nature. This is worse that a true state of nature because in that true state it is at least the fact that every man has the liberty to judge the rights granted him by the law of nature and how best his power would affect the maintenance thereof. This does not exist under a monarch who has total legislative and executive power.

Implication from this definition on commonwealths:

Within commonwealths all criminal acts which invade the citizen of the commonwealth’s ability and right to adjudication by common judge grant immediately this citizen the original rights of preservation and the power to carry them out under the laws of nature where civil society does not exist. This is due to the fact that all criminal acts threaten the continued longevity of any citizen, as a victim of crime, as a living being whether it be physical, economic, or some other area of living. No action is undertaken which does not preserve the life of the citizen as stipulated in Locke’s discussion of property and so any action taken against a citizen which interferes with their property or life immediately subjects both criminal and citizen of the commonwealth back into a state of nature where power to obtain themselves granted by the law of nature is all men’s right.

Further, who may be the judge of what actions are the most prudent in any incident where an individual is threatened by acts of criminality other than that man so threatened? There can be none outside of the victim of crime and so he now, as stated above, returns to his natural state as individual judge and executioner so as to maintain the preservation of his life.

Commentary: Under Locke’s definitions and arguments, we are to expect a utopia implicatively, wherein there is no crime otherwise all civil societies are merely a hollow shell of a perfect idealization of human rationality aimed at achieving this civil society. Locke’s own standards are untenable in the face of reality. Not only are they untenable but his criticisms of the monarch render his theory one of unfettered collectivism wherein the body politic makes no deference to the individual as to what counts as normative. Rather, Locke (and the Lockean commonwealth) defers to the wisdom and consent of the people and whereby upon resigning to the public their individual executive and legislative rights granted by the Law of Nature submits themselves to a tyranny of public opinion and the fluidity and fickle nature of human desires. In exchanging the monarch for a commonwealth the collective peoples have rendered themselves dominated men under a monarchy of many acting as one.