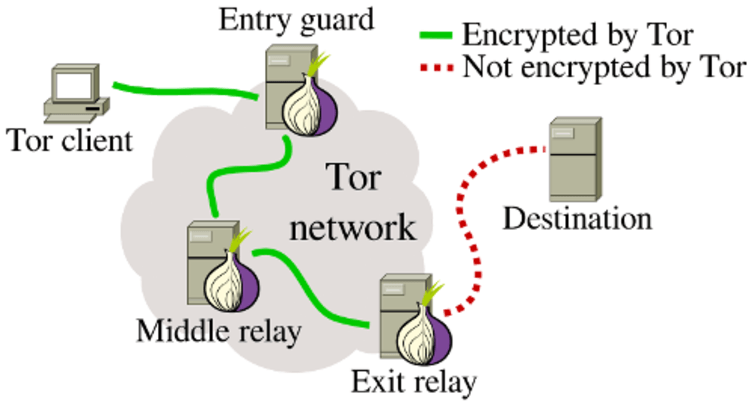

Tor is the network that the Daily Stormer relied on when we were being banned from every nation’s domain system. It’s a protocol designed by the government, probably primarily to bypass China’s censorship so they can spread whatever they want to spread there.

For example, the New York Times, which has a Mandarin version that publishes CIA propaganda against the government of China, runs a Tor site.

There is no mention of this in the mainstream media.

The censoring of an anti-censorship supporter is being censored.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, an anti-internet censorship group that doesn’t really do anything but get attention and donations (it is run by the Jews), are the only ones covering it.

Rainey Reitman writes:

Larry Brandt, a long-time supporter of internet freedom, used his nearly 20-year-old PayPal account to put his money where his mouth is. His primary use of the payment system was to fund servers to run Tor nodes, routing internet traffic in order to safeguard privacy and avoid country-level censorship. Now Brandt’s PayPal account has been shut down, leaving many questions unanswered and showing how financial censorship can hurt the cause of internet freedom around the world.

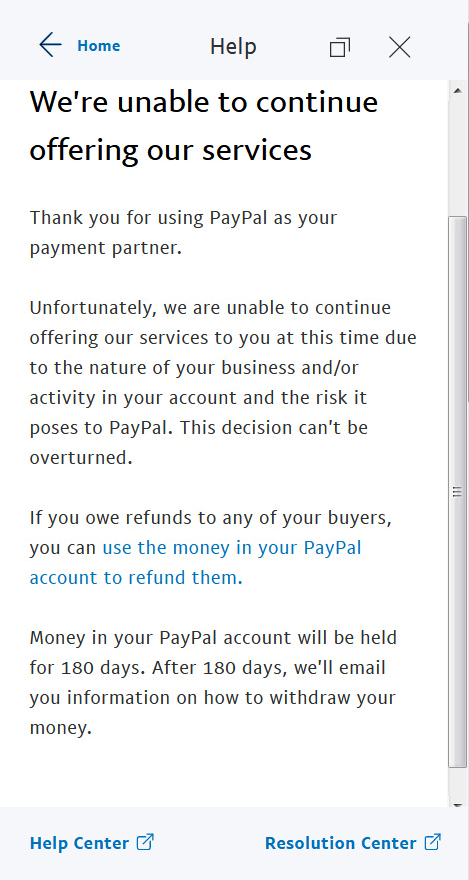

Brandt first discovered his PayPal account was restricted in March of 2021. Brandt reported to EFF: “I tried to make a payment to the hosting company for my server lease in Finland. My account wouldn’t work. I went to my PayPal info page which displayed a large vertical banner announcing my permanent ban. They didn’t attempt to inform me via email or phone—just the banner.”

Brandt was unable to get the issue resolved directly through PayPal, and so he then reached out to EFF.

For years, EFF has been documenting instances of financial censorship, in which payment intermediaries and financial institutions shutter accounts and refuse to process payments for people and organizations that haven’t been charged with any crime. Brandt shared months of PayPal transactions with the EFF legal team, and we reviewed his transactions in depth. We found no evidence of wrongdoing that would warrant shutting down his account, and we communicated our concerns to PayPal. Given that the overwhelming majority of transactions on Brandt’s account were payments for servers running Tor nodes, EFF is deeply concerned that Brandt’s account was targeted for shut down specifically as a result of his activities supporting Tor.

We reached out to PayPal for clarification, to urge them to reinstate Brandt’s account, and to educate them about Tor and its value in promoting freedom and privacy globally. PayPal denied that the shutdown was related to the concerns about Tor, claiming only that “the situation has been determined appropriately” and refusing to offer a specific explanation. After several weeks, PayPal has still refused to reinstate Brandt’s account.

The Tor Project echoed our concerns, saying in an email: “This is the first time we have heard about financial persecution for defending internet freedom in the Tor community. We’re very concerned about PayPal’s lack of transparency, and we urge them to reinstate this user’s account. Running relays for the Tor network is a daily activity for thousands of volunteers and relay associations around the world. Without them, there is no Tor—and without Tor, millions of users would not have access to the uncensored internet.”

One of the particularly concerning elements of Brandt’s situation is how automated his account shut down was. After his PayPal account was shuttered, Brandt attempted to reach out to PayPal directly. As he explained to EFF: “I tried to contact them many times by email and phone. PayPal never responded to either. They have an online ‘Resolution Center’ but I never had a dialog with anyone there either.” The PayPal terms reference the Resolution Center as an option, but asserts PayPal has no obligation to disclose details to its users.

Many online service providers make it difficult or impossible for users to reach a human to resolve a problem with their services. That’s because employing people to resolve these issues often costs more than the small amounts they save by reinstating wrongfully banned accounts. Internet companies just aren’t incentivized to care about customer service. But while it may serve companies’ bottom lines to automate account shut downs and avoid human interaction, the experience for individual users is deeply frustrating.

EFF, along with the ACLU of Northern California, New America’s Open Technology Institute, and the Center for Democracy and Technology have endorsed the Santa Clara principles, which attempt to guide companies in centering human rights in their decisions to ban users or take down content. In particular, the third principle is that “Companies should provide a meaningful opportunity for timely appeal of any content removal or account suspension.” Our advocacy has already pressured companies like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube to endorse the Santa Clara principles—but so far, PayPal has not. Brandt’s account was shut down without notice, he was given no opportunity to appeal, and he was given no clarity on what actions resulted in his account being shut down, nor whether this was in relation to a violation of PayPal’s terms – and, if so, which part of those terms.

We are concerned about situations such as Brandt’s not only because of the harm and inconvenience caused to one user, but because of the societal harms from patterns of account closures. When a handful of online payment services can dictate who has access to financial services, they can also determine which people and which services get to exist in our increasingly digital world. While tech giants like Google and Facebook have come under fire for their content moderation practices and wrongfully banning accounts, financial services haven’t gotten the same level of scrutiny.

But if anything, financial intermediaries should be getting the most scrutiny. Access to financial services directly impacts one’s ability to survive and thrive in modern society, and is the only way that most websites can process payments. We’ve seen the havoc that financial censorship can wreak on online booksellers, music sharing sites, and the whistleblower website Wikileaks. PayPal has already made newsworthy mistakes, like automatically freezing accounts that have transactions that mention words such as “Syria.” In that case, PayPal temporarily froze the account of News Media Canada over an article about Syrian refugees that was entered into their annual awards competition.

This is almost certainly the beginning of a campaign of attacking Tor.

They will go after the funding first. They always go after the funding first, and then ratchet it up.

There is limited ability to censor the anti-censorship platform, but they can start to push lawsuits on them and call for government action. The anonymity does make Tor a haven for child porn and terrorism, along with anti-Semitic jokes and corona hatefacts. They’re after the anti-Semitic jokes and corona hatefacts, but they will start talking about the other stuff, and accuse Tor of enabling it. They will come out with horror stories and so on.

Frankly, an attack on Tor is scary, because very few people use it. It tells you that they are planning to up the censorship way worse, and presumably also do horrible things to people and cover it up. They are trying to block the exits.