As Vladimir Putin pushes anti-gay agenda, vigilante movements gain momentum on social media

Amar Toor

The Verge

August 8, 2013

Last year, a teenager named “Alexei” (not his real name) was aimlessly surfing the web from his home in Moscow when he came across a curious collection of YouTube videos. Each clip featured different people, but they all followed the same basic script: a middle-aged man enters the scene expecting to have sex with a teenage boy he met on a dating website. Instead, he’s greeted by a group of young Russians who proceed to lecture, humiliate, and abuse him.

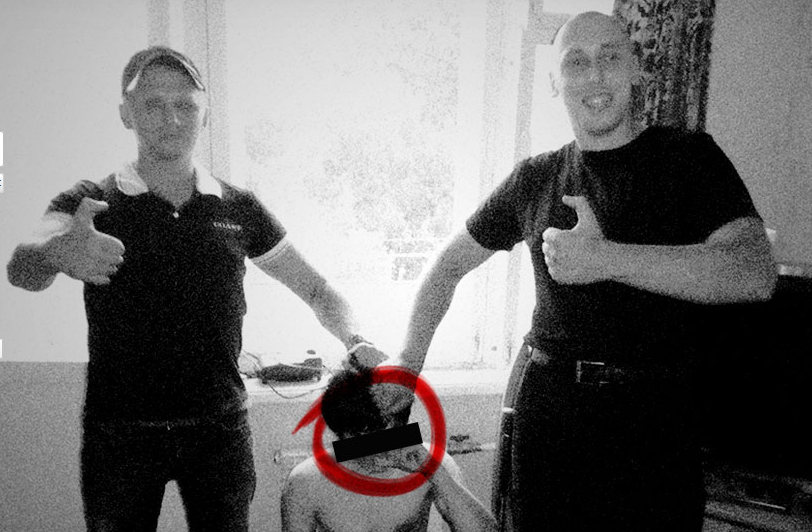

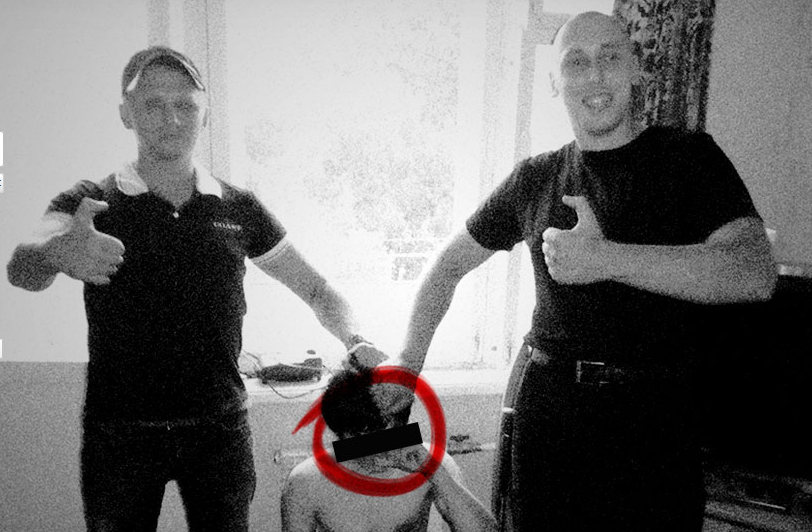

Within minutes, the plot is laid bare. The boy he met online was a decoy — a fake online persona created to lure him into a trap. Like spiders toying with a fresh fly, the young Russians behind the operation ridicule and excoriate the alleged pedophile, forcing him to pose with dildos, painting his face, and pouring urine over his head. A cellphone catches it all on video, but cuts off just as the group begins kicking and punching him.

The videos can be difficult to watch, but for Alexei, they were fascinating. “It’s entertainment to me,” the 20-year-old said in an interview with The Verge. “It’s about seeing the emotions.”Alexei has never been directly involved with any of the videos, though he supports the people who produce them — a loose collective of neo-Nazis and Russian nationalists known as “Occupy Pedofilyay” (Occupy Pedophilia). Both Occupy Pedofilyay and its smaller sister movement, “Occupy Gerontilyaj” (Occupy Gerontophilia), have garnered a substantial following on Russian social media over the past year, spawning hundreds of fan pages and dedicated satellite groups on VKontakte (VK) — Russia’s Facebook equivalent. Both are modeled on the same form of vigilante justice, and they target different sides of the same coin; Occupy Pedofilyay aims to catch pedophiles, while Gerontilyaj focuses on teenage boys who agree to have sex with older men, allegedly in exchange for money. Neither movement is explicitly anti-gay, though there are strong undercurrents of homophobia to each; thus far, only gay men and boys have been targeted.

People who belong to these groups say they serve a greater good by publicly humiliating alleged pedophiles, based on the pretext that their videos will deter others from engaging in similar behavior: pursue sex with a boy, and the entire world will watch you drink urine on camera. But opponents describe their tactics as crude, violent, and reckless. And in light of President Vladimir Putin’s recent crackdown on gay rights, some worry that the movements will only gain momentum going forward — fanning the flames of hate and bigotry as the Kremlin looks to shore up support among its conservative base.

“Being outed in a small city or village in Russia very often means death,” says Larry Poltavtsev of the Spectrum Human Rights Alliance, a Washington, DC-based advocacy group for gay rights in Eastern Europe. “Exposed teenagers may commit suicide, or they’ll be harassed by your peers, their parents may kick them out of their house. It’s a nightmare.”

Late last month, Poltavtsev published a disturbing video of a 15-year-old boy being interrogated by an Occupy Gerontilyaj contingent. For 20 minutes, the group of teenagers mock and lecture the boy, forcing him to admit that he came there to prostitute himself and making him repeat his full name on camera. They chastise him not only for agreeing to have sex for money, but for claiming to be bisexual, as well. The entire scene is framed like a mean-spirited intervention, as the teens urge the boy to change his ways while simultaneously hurling insults at him. The video comes to an abrupt end once the gang begins kicking him, after having already doused his head in what they claim to be urine. (“This will cure you of homosexuality,” one says.)

“Being outed in a small city or village in Russia very often means death.”

At one point in the video, the teens force the boy to praise Maxim “Slasher” Martsinkevich — a 29-year-old former skinhead who created the Occupy Pedofilyay movement in 2012. Musclebound and mohawked, Martsinkevich recently served a three-and-a-half year prison sentence for staging and filming a fake execution of a Central Asian drug dealer in 2009. In the video, he and his neo-Nazi cohorts were shown dressed in Ku Klux Klan robes as they pretended to hang and dismember the purported drug dealer. A Russian court found him guilty of provoking ethnic hate crimes.

Upon his release, Martsinkevich created Restrukt (“Restructuring”) — a vaguely defined “social movement” with distinctly nationalist overtones. Its manifesto calls for the creation of a “fundamentally new union of Russian people,” in the hopes of reversing the country’s “degradation.”

The group is strictly anti-drug and alcohol, and places a curious emphasis on exercise and bodybuilding. Martsinkevich regularly posts bare-chested pictures of himself on VK and Instagram, and promotes himself as a sports nutritionist and fitness guru. Swastikas and protein powder figure prominently in his online persona, and many of his followers describe him as a sort of moral leader.

Restrukt representatives insist that Martsinkevich is no longer personally involved in politics, though the organization allies itself with Russia’s National-Socialist Party — a neo-Nazi group that garnered international notoriety in 2007, when it decapitated an ethnic minority on video. Prior to his arrest, Martsinkevich led Format18, a neo-Nazi collective that spread anti-immigrant vitriol and violent videos across the web.

Anzhey Kmitits, one of Martsinkevich’s “comrades” at Restrukt, says the organization has grown rapidly in recent months. He claims to have established 10 regional offices across Russia, estimating that there are more than 500 activists currently engaged in its ongoing “social projects” — including Occupy Pedofilyay.

“Pedophilia, in our understanding, is an important indicator of the state of society — its flaws and weaknesses,” Kmitits said in a translated VK message to The Verge. “We strive to help the public become better and stronger, to assume some of the functions of the state, which itself is neither willing nor able to deal with such problems.”

There are hundreds of active VK groups devoted to Occupy Pedofilyay or Gerontifilyay. The largest has more than 75,000 followers, and 20 other groups have more than 1,000. Their common symbol is a bent thumbs-up sign, modeled after the Facebook “like” icon, though Kmitis says it has no special significance.

Martsinkevich’s well-manicured persona has inspired a legion of young cult followers to follow in his footsteps. Occupy Gerontifilyay was started in 2012 by Philip Dyonits, a 16-year-old Slasher protege who used to lure alleged pedophiles with fake dating profiles before breaking off to launch his own group.

Occupy Peodfilyay’s regional affiliate groups are guided by Martsinkevich’s basic ideology — he regularly publishes stylized videos and holds regional seminars — though they operate in different ways. Some clearly resort to physical violence during sting operations (or “safaris,” as they’re called) while others take a more hands-off approach. Dmitry Mikolenko, founder of the Occupy Pedofilyay movement in Kiev, Ukraine, says he doesn’t think violence is “meaningful,” adding that moral abuse is more effective than physical aggression. He acknowledges, however, that his group frequently douses its “live bait” with urine.

The groups also differ in their respective philosophies on law enforcement. Mikolenko says he has no intention of cooperating with local police, alleging that authorities in Kiev are intent on “protecting pedophiles.” But Kmitits and others say they’re on good terms with the police, with some claiming that they closely coordinate their operations.

“They know us,” says Alexander Mikheev, leader of the Occupy Pedofilyay movement in the Russian city of Irkutsk. “We work closely with them, and if we have solid evidence, we call the police and give [the suspect] over.”

The extent to which Martsinkevich dictates Occupy Pedofilyay’s agenda remains unclear. Kmitits says his colleague is in charge of the movement’s Moscow headquarters, and that the various satellite branches are “semi-autonomous.” It is clear, though, that his persona and notoriety have garnered a broader cult following. Both Mikheev and Mikolenko say they’ve never met Martsinkevich in person, and started their respective branches after learning of the movement online.