It’s not going to work for a nuclear war.

Not these ones they’re selling.

A deep one works.

But some kind of bunker may help you in the case of some other sort of disaster.

AP:

When Bernard Jones Jr. and his wife, Doris, built their dream home, they didn’t hold back. A grotto swimming pool with a waterfall for hot summer days. A home theater for cozy winter nights. A fruit orchard to harvest in fall. And a vast underground bunker in case disaster strikes.

“The world’s not becoming a safer place,” he said. “We wanted to be prepared.”

Under a nondescript metal hatch near the private basketball court, there’s a hidden staircase that leads down into rooms with beds for about 25 people, bathrooms and two kitchens, all backed by a self-sufficient energy source.

With water, electricity, clean air and food, they felt ready for any disaster, even a nuclear blast, at their bucolic home in California’s Inland Empire.

“If there was a nuclear strike, would you rather go into the living room or go into a bunker? If you had one, you’d go there too,” said Jones, who said he reluctantly sold the home two years ago.

Global security leaders are warning nuclear threats are growing as weapons spending surged to $91.4 billion last year. At the same time, private bunker sales are on the rise globally, from small metal boxes to crawl inside of to extravagant underground mansions.

Critics warn these bunkers create a false perception that a nuclear war is survivable. They argue that people planning to live through an atomic blast aren’t focusing on the real and current dangers posed by nuclear threats, and the critical need to stop the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

Meanwhile, government disaster experts say bunkers aren’t necessary. A Federal Emergency Management Agency 100-page guide on responding to a nuclear detonation focuses on having the public get inside and stay inside, ideally in a basement and away from outside walls for at least a day. Those existing spaces can provide protection from radioactive fallout, says FEMA.

But increasingly, buyers say bunkers offer a sense of security. The market for U.S. bomb and fallout shelters is forecast to grow from $137 million last year to $175 million by 2030, according to a market research report from BlueWeave Consulting. The report says major growth factors include “the rising threat of nuclear or terrorist attacks or civil unrest.”

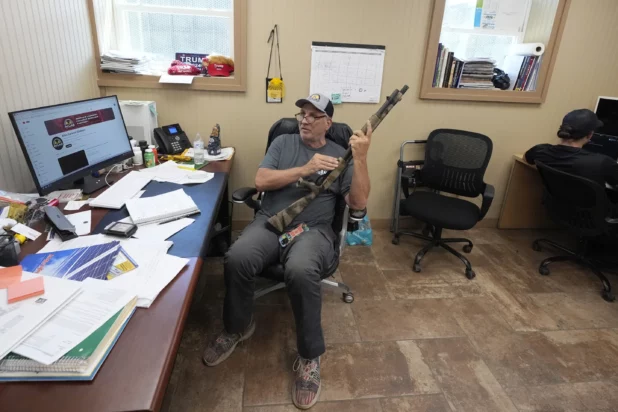

“People are uneasy and they want a safe place to put their family. And they have this attitude that it’s better to have it and not need it then to need it and not have it,” said Atlas Survival Shelters CEO Ron Hubbard, amid showers of sparks and the loud buzz of welding at his bunker factory, which he says is the world’s largest, in Sulphur Springs, Texas.

Hubbard said COVID lockdowns, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war have driven sales.

On Nov. 21, in the hours after Russia’s first-ever use of an experimental, hypersonic ballistic missile to attack Ukraine, Hubbard said his phone rang nonstop.

Ron Hubbard

Nonproliferation advocates bristle at the bunkers, shelters or any suggestion that a nuclear war is survivable.

“Bunkers are, in fact, not a tool to survive a nuclear war, but a tool to allow a population to psychologically endure the possibility of a nuclear war,” said Alicia Sanders-Zakre at the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons.

Sanders-Zakre called radiation the “uniquely horrific aspect of nuclear weapons,” and noted that even surviving the fallout doesn’t prevent long-lasting, intergenerational health crises. “Ultimately, the only solution to protect populations from nuclear war is to eliminate nuclear weapons.”

Researcher Sam Lair at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies says U.S. leaders stopped talking about bunkers decades ago.

“The political costs incurred by causing people to think about shelters again is not worth it to leaders because it forces people to think about what they would do after nuclear war,” he said. “That’s something that very, very few people want to think about. This makes people feel vulnerable.”

Lair said building bunkers seems futile, even if they work in the short term.

“Even if a nuclear exchange is perhaps more survivable than many people think, I think the aftermath will be uglier than many people think as well,” he said. “The fundamental wrenching that it would do to our way of life would be profound.”

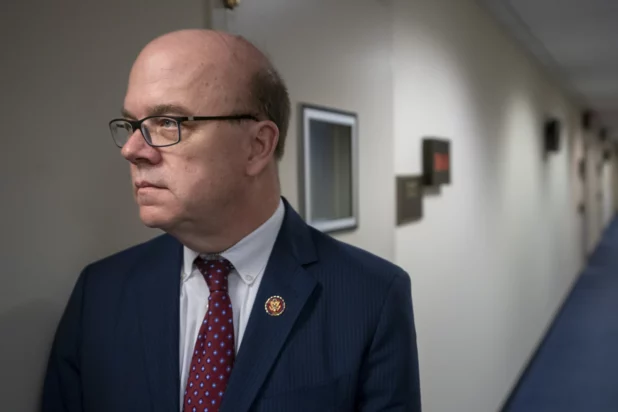

That’s been a serious concern of Massachusetts Congressman James McGovern for almost 50 years.

“If we ever get to a point where there’s all out nuclear war, underground bunkers aren’t going to protect people,” he said. “Instead, we ought to be investing our resources and our energy trying to talk about a nuclear weapons freeze, initially.”

James McGovern

McGovern pushed back against FEMA’s efforts to prepare the public for a nuclear attack by advising people to take shelter.

“What a stupid thing to say that we all just need to know where to hide and where to avoid the most impacts of nuclear radiation. I mean, really, that’s chilling when you hear people try to rationalize nuclear war that way,” he said.

You are going to want to cover the hatch.

That’s important.

You don’t want someone stumbling on your hatch and opening it to get your food.

Ultimately though, once the apocalypse comes, you are going to want to be mobile, at least for the first year while you’re waiting for the blacks to die off.