Kevin MacDonald

Occidental Observer

February 5, 2015

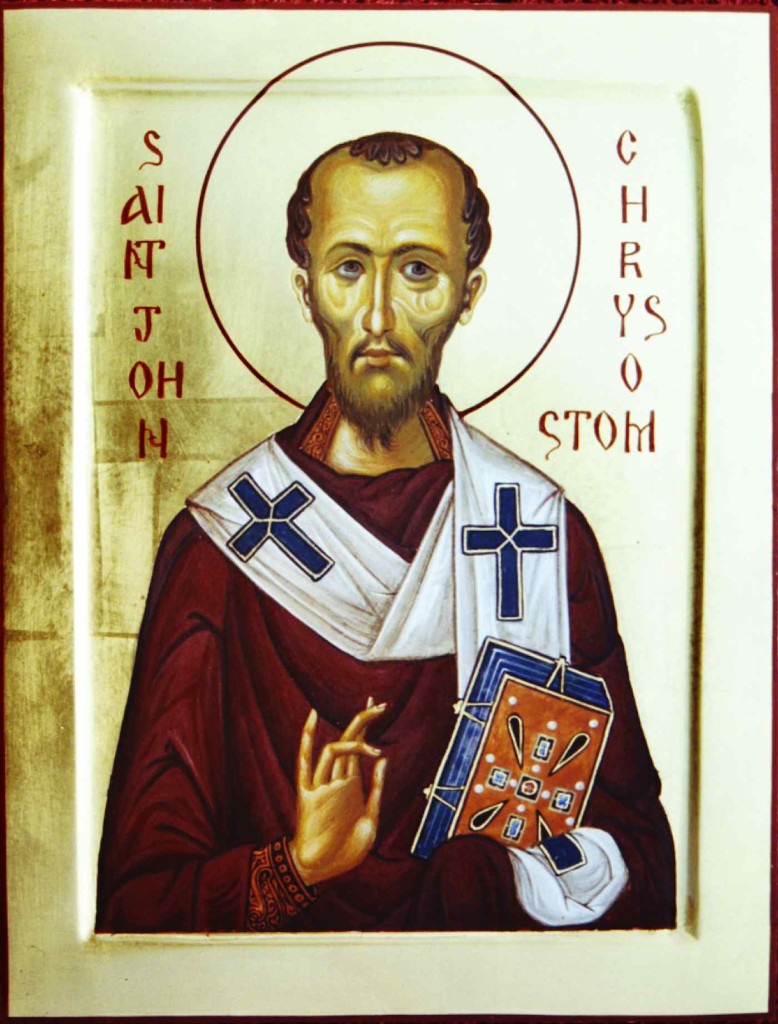

A correspondent just notified me of a blog post from 2010 on St. John Chrysostom by Roger Pearse, a scholar of Christianity in the ancient world (“Some remarks about John Chrysostom’s homilies against the Jews“). Pearse quotes from a 1935 summary of Chrysostom’s writings whose author, A. L. Williams, notes that Chrysostom was motivated by the fact that many Christians were

frequenting Jewish synagogues, were attracted to the synagogal Fasts and Feasts, sometimes by the claims to superior sanctity made by the followers of the earlier religion, so that an oath taken in a synagogue was more binding than in a church, and and sometimes by the offer of charms and amulets in which Jews of the lower class dealt freely.

Williams concluded:

We gather from these Homilies that the Jews were a great social, and even a great religious, power in Antioch.

Exactly. As discussed in Chapter 3 of Separation and Its Discontents, the phenomenon of Judaizing Christians in the ancient world is a marker of Jewish power at the time. For example, the rather limited anti-Jewish actions of the government during the 150 years following the Edict of Toleration of 313, which included many attempts to ban the common practice of Jews enslaving non-Jews, are interpreted by historian Bernard S. Bachrach “as attempts to protect Christians from a vigorous, powerful, and often aggressive Jewish gens.” Jews as a powerful group were looked up to and emulated by many non-Jews, just as today we see the same phenomenon, not only among many Evangelical Christians, but also Hollywood celebrities who dabble in kabbalah and pretty much the entire non-Jewish political class which we see making pilgrimages to Israel and proudly wearing yarmulkes and displaying menorahs during photo-ops.

This is also relevant to the Jewish IQ debate, where Greg Cochran and Henry Harpending have developed a theory of Ashkenazi uniqueness that implies no particular intellectual distinction for Jews in the ancient world. On the contrary, after the failed rebellions of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, Jews became very powerful throughout the Roman Empire and certainly by the 4th century when Chrysostom wrote.

Chryostom was not only concerned about non-Jews who were trying to curry the favor of the powerful Jewish community, he also had a very negative view of Jews in general:

[The Synagogue] is not merely a lodging place for robbers and cheats but also for demons. This is true not only of the synagogues but also of the souls of the Jews. (I.IV.2)

Shall I tell you of their plundering, their covetousness, their abandonment of the poor, their thefts, their cheating in trade? (I.VII.1) (St. John Chrysostom,Adversus Judaeos)

Such sentiments were common among the other Church Fathers of the period. Indeed, in the words of one scholar, “a significant percentage of all Christian writings during the period are essentially adversos Judeaos” (here, p. 103).

Pearse comments that what was really going on was ethnic warfare between religiously defined ingroups and outgroups:

As with so much else in the later Roman Empire, Christianity had become a badge of a community, rather than the means of salvation. Chrysostom was merely defending the “turf” of the group who had elected him their bishop.

This again is the thesis of Chapter 3 of Separation and Its Discontents.

Jews were to be conceptualized not as harmless practitioners of exotic, entertaining religious practices, or as magicians, fortune tellers, or healers, but as the very embodiment of evil. The entire thrust of the legislation that emerged during this period was to erect walls of separation between Jews and gentiles, to solidify the gentile group, and to make all gentiles aware of who the “enemy” was. Whereas these walls had been established and maintained previously only by Jews, in this new period of intergroup conflict the gentiles were raising walls between themselves and Jews. And while Jews may have been happy to attract the sympathy of elite gentiles by encouraging Judaizing, Judaizing would be anathema to anti-Jewish leaders, who would insist that the walls between groups be high and that each person belong to only one group. During this period of group conflict, there could be no half-way commitment to either group. As Chrysostom himself said, “ ‘Fortify one another.’ If a catechumen is sick with this disease, let him be kept outside the church doors. If the sick one be a believer and already initiated, let him be driven from the holy table. . . . The wounds that have festered and cannot be cured, those which are feeding on the rest of the body, need cauterization with a point of steel” (Adversus Judaeos II.III.6). The battle between groups must commence. In the long run, the consequences of this Christian group strategy would be a general lowering of the economic and reproductive prospects of the Jewish community.

Christians have to come to grips with the fact that the Catholic Church originated in the ancient world as a group strategy to combat the power of the Jews (short version here). Obviously, it hasn’t always functioned in that manner, particularly since Vatican II. But that’s how it started, and much of this anti-Jewish ideology in which Jews were a dangerous and feared outgroup and that a major function of the Church was to protect Christians from Jews continued into the 20th century as official Church doctrine (see previous link).