Benjamin Garland

Daily Stormer

March 7, 2017

Part 1, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9

“Those in the know realize that Jews almost single-handedly built the comic-book industry from the ground up” – Arie Kaplan1

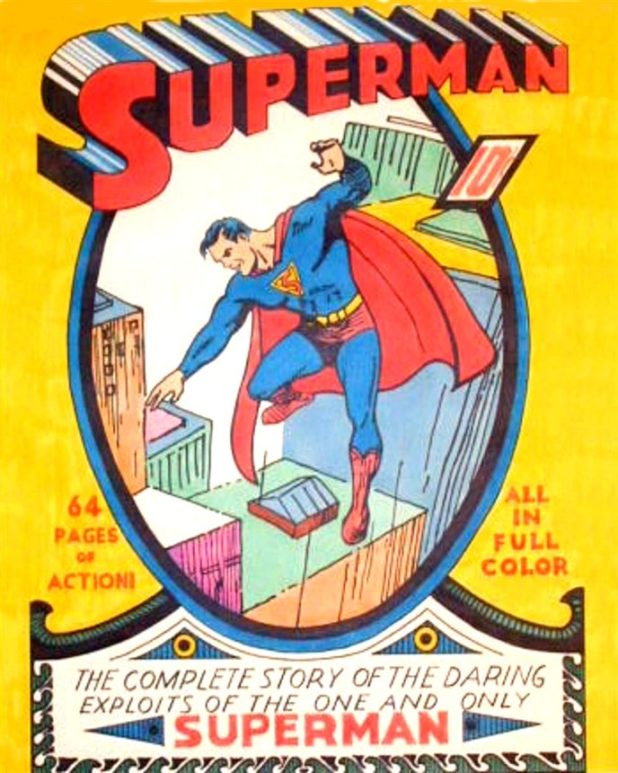

The modern day comic-book was created by the Jew Max Gaines (born Ginzberg), in 1933. He had been re-reading some newspaper comic strips when he decided that packaging them into fold-out, or book form, may be a profitable venture.

The comic-book industry has been almost entirely Jewish ever since.

Throughout the remainder of the 30s and into the 40s, comic-books became increasingly extreme, as is typical of Jewish behavior in any industry when left unchecked (the Weimar Republic and “Pre-code” Hollywood provide us with much recent evidence for this), and also due to the fact that people are naturally attracted to taboo topics.

The taboo factor caused a competitive drive for comic-book publishers to continually push the envelope, as those who did usually garnered a much larger readership than those who tried to keep it relatively clean.

Public alarm over comic-books grew with time because of this. The first significant nation-wide attention brought to comics’ potential harm on children was a widely read 1940 article, written by Sterling North, in which he characterized comic-books as “poisonous mushrooms” that were corrupting and dumbing down the youth of the nation.

Years later, with uncanny timing, on March 29, 1948 – the very day of the Supreme Court’s Winters v. New York decision (see part 1) – an influential article titled ‘Puddles of Blood,’ which reported on an alleged scientific inquiry into the dangers of comic-books, was published in Time magazine.

This article, and subsequent similar ones published in such widely read outlets as the Saturday Review of Literature, Reader’s Digest and Ladie’s Home Journal, spurred much public concern and numerous attempts at passing anti-comics legislation across the country, all of which was thwarted by the precedent of Winters v. New York.

The far-reaching impact of these articles was due to the seeming credibility of the man behind them: famed Jewish psychiatrist Dr. Fredric Wertham, who promoted the theory that comic-books were a corrupting influence that could push the young toward crime and sexual perversion.

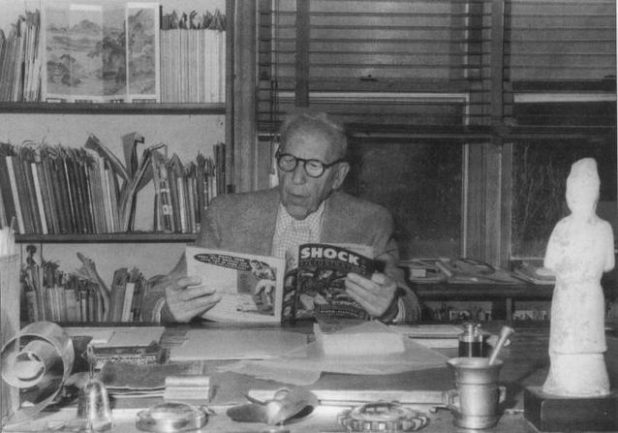

Dr. Fredric Wertham

Fredric Wertham, born Friedrich Wertheimer in Germany in 1895, was a Freudian psychoanalyst, psychiatrist and critical theorist of the Frankfurt School variety (see part 5).2

Wertham was an interesting character. Today he would be known as a Social Justice Warrior, or SJW, as his primary concern was finding ways to excuse the disproportionate rate of crime committed by non-Whites as compared to Whites, such as “institutional racism.”

Wertham was quite influential in this regard, even having his writings on the alleged detrimental effects of racial segregation cited as authoritative in the infamous Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision that forcibly integrated American schools.

This is also obviously what was behind his attacks on comic-books, yet this is either overlooked by historians, or just goes unmentioned due to political correctness.

In 1946, he opened the first psychiatric clinic specifically designed to help poor Blacks in Harlem, New York City, where, at that time, the 98% Black population, despite making up only 3% of New York City’s total, was responsible for more than 50% of its cases of juvenile delinquency.3

There he employed a multi-ethnic staff whose “main criterion for employment was a subscription to the idea of ‘universalism,’” i.e. the belief that race doesn’t exist and that everyone is born equal with a “blank slate,” and then molded by their surrounding circumstances.4

Like many of the SJW types, Wertham was not above using brazenly dishonest methods to achieve his preconceived notions (the full extent of which is only now being realized since the release of his archives in 2010).5

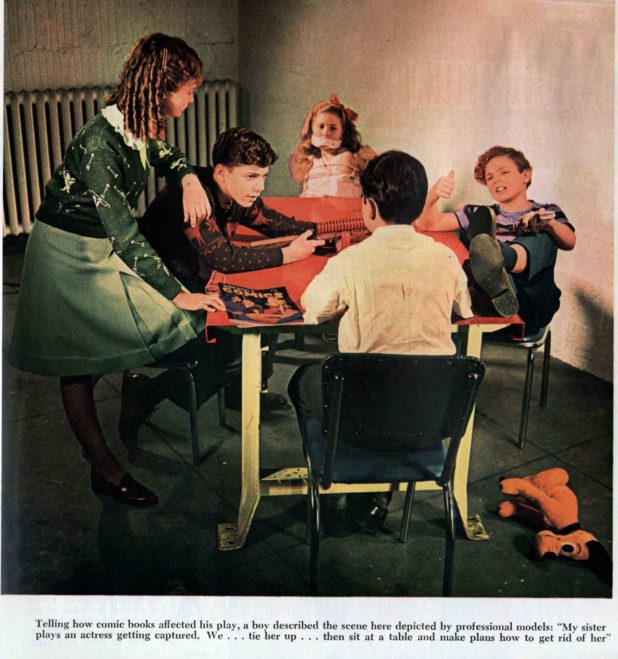

Collier’s magazine ran an article on Wertham titled “Horror in the Nursery.” “Strangely,” David Hajdu wrote in his book The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare and How it Changed America, “[“Horror in the Nursery”] never mentioned that the location of Wertham’s research site was Harlem.”

Instead, Hadju wrote, it evoked

associations with WASPy Anglicanism without a hint of how far uptown the Lafargue Clinic was. The text never mentioned Negro culture or, for that matter, race or ethnicity in any context; and all the children in the photographs, which were staged, were white.6

Wertham’s writings against comics were full of many bizarre and outrageous claims, such as that Superman – a character that was created by Jews and symbolically modeled on the Jewish experience of being an alien race having to blend in among the gentiles – was a Nazi and a Fascist.

Nevertheless, people were ripe for a professional to tell them what they had been suspecting about comic-books for some time, so Wertham’s theories got a lot of mileage, and he became the figurehead of the anti-comics crusade.

Image from ‘Horror in the Nursery’ depicting the children as all White, despite the fact that Wertham’s clinic was in Harlem, New York, which was 98% Black.

Image from ‘Horror in the Nursery’ depicting the children as all White, despite the fact that Wertham’s clinic was in Harlem, New York, which was 98% Black.

Following the Second World War, the American public was searching for reasons to explain why juvenile delinquency was on the rise. The idea that race and genetics play a significant role in one’s behavior was out of fashion due to its association with Nazis, who America and much of the world had just been at war with, and the simultaneous rise of “cultural anthropology,” which claims that race is nothing more than skin color, a “social construct.”

Franz Boas, the popularizer of “cultural anthropology,’ was another German born Jew who falsified data to bolster an anti-racist agenda, driven by the not unfounded fear that physical anthropology and racial science, which had been flourishing in the 20s and 30s, would lead to increasing anti-Semitism.7

So with race and genetics effectively off of the table as an explanation for juvenile delinquency, sociologists were forced to go searching for other theories (bad parenting, discrimination, poor social conditions, etc.) to explain its increase. Wertham and others blamed comic-books, and parents listened.

The 1953 article “What Parents Don’t Know About Comic Books,” which featured excerpts of Wertham’s forthcoming book on the dangers of comic-books, Seduction of the Innocent, caused quite a stir. It prompted the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, which had been formed around that same time, to launch a full-scale investigation into comic-books and the comic-book industry.

Over 3 days in April and June of 1954, the Senate Subcommittee held hearings on comic-books which were broadcast live on television.

The only comic-book publisher to testify was the eccentric Jew William Gaines, who had inherited EC Comics from his deceased father, the aforementioned inventor of the modern comic Max Gaines. Gaines was the second to testify, following Wertham, and what he said forever shook the comic-book industry to its core.

Gaines’s demeanor was that of defiance. Instead of attempting to make a positive case for his industry in order to convince the public that they weren’t so bad, he behaved with reckless arrogance – chutzpah, the Jews call it.

“I publish horror comics,” he bragged to the committee. “I was the first publisher in these United States to publish horror comics. I am responsible, I started them.”

“Some may not like them,” he continued. “That is a matter of personal taste. It would be just as difficult to explain the harmless thrill of a horror story to a Dr. Wertham as it would be to explain the sublimity of love to a frigid old maid.”8

William Gaines

William Gaines

The majority of the questioning was to resolve whether or not comic-books could have a negative influence on their young readers, and Gaines walked himself right into a trap. He admitted that he deliberately used comics to combat racism and anti-Semitism, and this notion was immediately seized upon, by its obvious implication: if comics could affect children’s thought process in a positive way (brainwashing children to not be anti-Semitic was understandably seen as positive to Gaines), then why could they not just as easily affect the children negatively?

Mr. BEASER: . . . You used the pages of your comic book to send across a message, in this case it was against racial prejudice; is that it?”

Mr. GAINES. That is right.

Mr. BEASER. You think, therefore, you can get across a message to the kids through the medium of your magazine that would lessen racial prejudice; is that it?

Mr. GAINES. By specific effort and spelling it out very carefully so that the point won’t be missed by any of the readers, and I regret to admit that it still is missed by some readers, as well as Dr. Wertham ─ we have, I think, achieved some degree of success in combating anti-Semitism, anti-Negro feeling, and so forth.

Mr. BEASER. Yet why do you say you cannot at the same time and in the same manner use the pages of your magazine to get a message which would affect children adversely, that is, to have an effect upon their doing these deeds of violence or sadism, whatever is depicted?

Mr. GAINES. Because no message is being given to them. In other words, when we write a story with a message, it is deliberately written in such a way that the message, as I say, is spelled out carefully in the captions.

The exchange that really shot Gaines, and the entire comic-book industry by extension, in the foot, was the following:

Mr. BEASER. There would be no limit actually to what you put in the magazines?

Mr. GAINES. Only within the bounds of good taste.

Mr. BEASER. Your own good taste and salability?

Mr. GAINES. Yes.

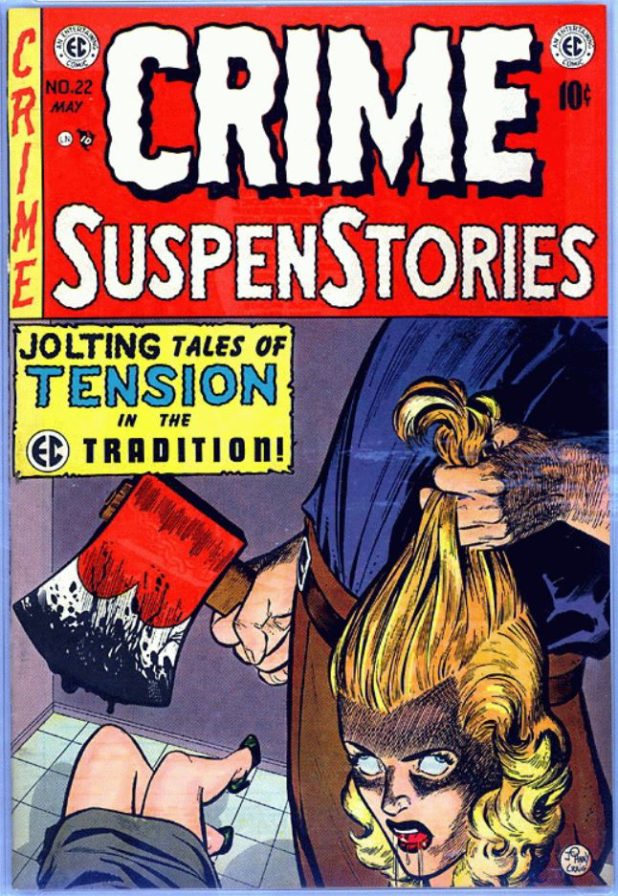

Senator KEFAUVER. Here is your May 22 issue. This seems to be a man with a bloody ax holding a woman’s head up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?

Mr. GAINES. Yes, sir; I do, for the cover of a horror comic. A cover in bad taste, for example, might be defined as holding the head a little higher so that the neck could be seen dripping blood from it and moving the body over a little further so that the neck of the body could be seen to be bloody.

Senator KEFAUVER. You have blood coming out of her mouth.

Mr. GAINES. A little.

Senator KEFAUVER. Here is blood on the ax. I think most adults are shocked by that.

The CHAIRMAN. Here is another one I want to show him.

Senator KEFAUVER. This is the July one. It seems to be a man with a woman in a boat and he is choking her to death here with a crowbar. Is that in good taste?

Mr. GAINES. I think so.9

That last exchange was plastered all over headlines and articles across the nation the next day. Parents were unsurprisingly shocked and horrified that Gaines, a man representative of the industry selling products to their children, would just nonchalantly say that a bloody severed head, and a woman being choked to death with a crowbar, were in “good taste.”

Following this, the comic-book industry promptly convened a meeting and decided on a self-imposed regulatory code, based on the Hays Code of Hollywood (see part 8), to preempt the anti-comic legislation that would now inevitably be passed against them otherwise.

The Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA), which had formed on September 7, 1954, devised a “Comics Code,” and thereafter all comics had to be screened by the Comics Code Authority to receive a “seal of approval,” or else be rejected by vendors.

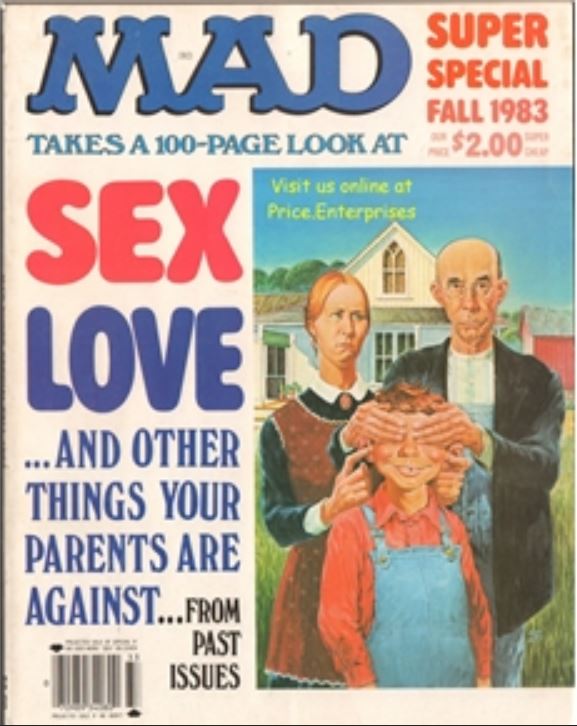

All of Gaines’s EC titles folded except, ironically, the most extreme of all: the infamous MAD, which he instead cleverly converted into a magazine to skirt the code regulation.

MAD was initially created by Harvey Kurtzman, who had been born and raised by Jewish communists (a “red-diaper baby”). It was – and still is – for all intents and purposes, intentionally offensive, Jewish toilet humor. An article in Haaretz in 2013 boasts that MAD “was very much humor in a Jewish vein” and that “Leo Rosten’s The Joys of Yiddish was a required companion text” for gentile readers.10

The content of MAD magazine is overt Jewish mockery of gentile American culture. The staff of MAD were always “antiparent,” and thus had it as an open agenda to turn children against their parents using, as one journalist put it, “relentless exposure of parental dishonesty.”11

Peter Kuper, a Jewish cartoonist who worked on MAD, said of the EC controversy: “It’s incredibly ironic that the House Un-American Activities Committee that attacked EC and essentially knocked them out for their subversive nature left them one thing standing and that was MAD Magazine, which was ultimately the most subversive thing that they ever produced.”12

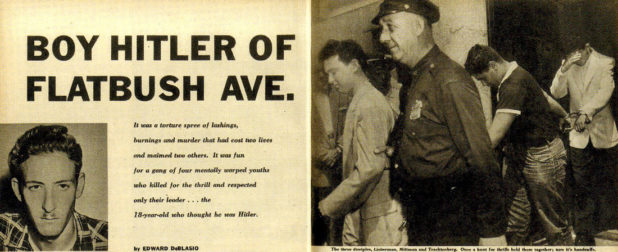

Roughly two months after the Senate Subcommittee hearings, and one before the implementation of the “Comics Code,” on August 16, 1954, a horrific and bizarre incident which seemed to validate Wertham’s assertions occurred: a bum washed up dead on the shores of New York, murdered by a gang of four teens, later dubbed the Brooklyn Thrill-Killers, who had stalked the streets for some time, sadistically attacking and torturing random, innocent people.

Mariah Adin wrote in her book The Brooklyn Thrill-Kill Gang and the Great Comic Book Scare of the 1950s that their

crime spree came straight from the pages of comic books: Some victims they tested their strength on, turning them into human punching bags. Others were tortured, their arms or legs wrapped in kerosene-soaked rags before one of the boys would strike a match. Some nights the group sought out young women in public parks, groping their exposed breasts after they had been stripped and flogged – a “popular game for kids,” the boys would joke. But their final crime that fateful summer of 1954, the one called the “supreme adventure’ by the gang’s leader, would result in the police’s dredging up the body of a middle-aged black man from the murky depths of the East River.13

All of the Brooklyn Thrill-Killers were Jewish. The leader, Jack Koslow, was a sado-masochistic, closeted homosexual and self proclaimed “White supremacist” and “neo-Nazi” who was obsessed with Adolf Hitler and Mein Kampf. This also characterized the other three to a greater or lesser extent, though Koslow was definitely the leader, and the one who actually committed murder and instigated most of the crimes.

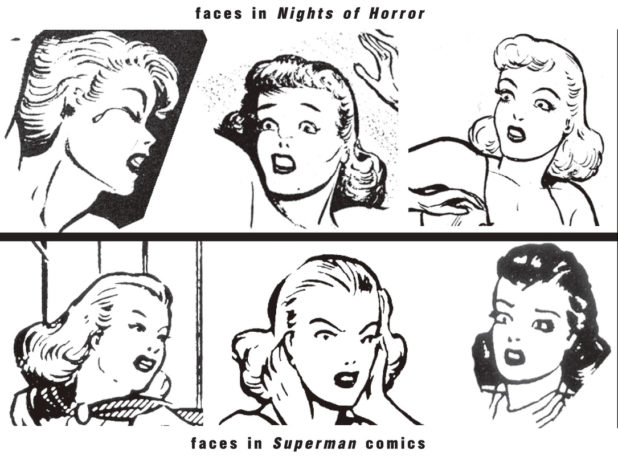

Wertham went to interview Koslow after his capture and during their talk it was revealed that Koslow was heavily influenced by a series of sado-masochistic underground comic-books called Nights of Horror, and was literally emulating what he found in them.

Jack was sexually excited by the “whipping” in the comics, and would occasionally dress up as a woman and self-flagellate, before moving on to whipping actual women who he found alone during the night in New York City. He would dress up as a vampire, just like a character in Nights of Horror, before going out on his sadistic whipping excursions, and he used a whip that he ordered from an ad in the back of a comic.14

Decades later, it was revealed by author Craig Yoe that the man behind the brutal, pornographic artwork in Nights of Horror was none other than Joe Shuster, co-creator of one of America’s all time most beloved cultural icons: Superman.15

Superman was first published by National Allied Publications (later to become DC), which was owned by Harry Donenfeld, a Jewish immigrant who had been a pornographer in the 20s and 30s before going into comics.

Donenfeld was one of the Jews who led the way in making comic-books increasingly extreme in the late 30s and 40s with titles such as Spicy Detective, Spicy Western and Spicy Adventure, drawing the ire of the NYSSV and the National Organization of Decent Literature, which described his comics as “wholly depraved and lascivious, and undoubtedly one of the deadliest plagues that ever threatened the moral life of a nation.”16

The self-imposed Comics Code tamed comics to a great degree and effectively brought the heat away from them and onto what was now seen as the biggest threat to the youth and morality of the nation: pornography.

“Only as the comics panic receded did pornography rise in public profile to replace it,” wrote Whitney Strub, in Perversion for Profit.17

The impact was instantaneous, New York’s Joint Legislative Committee on Comic Books suddenly reinvented itself as the Joint Legislative Committee on Obscene Material, while the Catholic magazine America abruptly shifted gears from comics to pornography.18

The Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency organized a new set of hearings which were held in May and June of 1955, this time on the topic of “obscene and pornographic materials.” All of those subpoenaed to the hearing for their dealings in pornography, as well as their attorneys, were Jews, excluding one Italian, Eugene Maletta, who was merely the printer of the Nights of Horror comic series.19

The two most well-known Jewish pornographers called before the committee were Eddie Mishkin and Samuel Roth. Mishkin was the distributor of the Nights of Horror comics series as well as a peddler of the worst sort of hardcore porn. He was finally indicted years later, and when the Supreme Court upheld his conviction they cited a former employee of his who testified that Mishkin demanded his authors made books

full of sex scenes and lesbian scenes. . . . [T]he sex had to be very strong, it had to be rough, it had to be clearly spelled out. . . . I had to write sex very bluntly, make the sex scenes very strong. . . . [T]he sex scenes had to be unusual sex scenes between men and women, and women and women, and men and men. . . . [H]e wanted scenes in which women were making love with women. . . . [H]e wanted sex scenes . . . in which there were lesbian scenes. He didn’t call it lesbian, but he described women making love to women and men . . . making love to men, and there were spankings and scenes — sex in an abnormal and irregular fashion. 20

All of the pornographers pleaded the fifth before the subcommittee, at the advice of their counsel, except for the hardheaded Samuel Roth. Two years later, in 1957, Roth would be the defendant in the most earth-shaking Supreme Court obscenity decision in American history, Roth v. United States.

In part 3 we will explore the case of Roth v. United States, before getting into the subsequent landmark decisions that were influenced by it, and how they opened the floodgates to pornography, in part 4.

If you enjoy this series, please consider supporting the author by purchasing a print copy.

Notes

- Arie Kaplan, From Krakow to Krypton: Jews and Comic Books, 2008, p.XIV

- Amy Nyberg, Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code, 1998, p.86

- Bart Beaty, Fredric Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture, 2005, p.90

- Mariah Adin, The Brooklyn Thrill-Kill Gang and the Great Comic Book Scare of the 1950s, 2014, p.67

- See Carol L. Tilley, “Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications That Helped Condemn Comics,” Information & Culture: A Journal of History, Volume 47, Number 4, 2012. Available electronically via Project Muse (DOI: 10.1353/lac.2012.0024)

- David Hajdu, The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare and How it Changed America, 1999, p.101-102

- See e.g. Kevin MacDonald, The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements, 1998. Chpt. 2

- United States Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency Hearings on Comic-Books, Transcript, p.98

- Ibid. p.103

- Nathan Abrams, “You Don’t Have to be Jewish to Be Mad … but It Helps,” Haaretz, November 13, 2013

- Stanley Rothman & Robert Lichter, Roots of Radicalism: Jews, Christians, and the Left, 1996, p.108; also Hadju, p.34

- Kaplan, p.77

- Adin, p.1

- Ibid, p.71

- See Craig Yoe, Secret Identity: The Fetish Art of Superman’s Co-creator Joe Shuster, 2009

- Ibid, p.11

- Whitney Strub, Perversion for Profit: The Politics of Pornography and the Rise of the New Right, 2011, p.22

- Ibid., p.25

- Those subpoenaed were: Samuel Roth, Edward Mishkin, Eugene Maletta David S. Alberts, Abraham Rubin, Louis Shomer, Arthur Herman Sobel, Irving Klaw, Abe Rotto; Counsel: H. Robert Levine, Daniel Weiss, Stanley Fleishman, Coleman Gangel, Leon Lazer, Jacob Rachstein, Morris Bohrar

- Mishkin v. New York, 383 U.S. 502, March 21, 1966 (ellipses in original)