Max Musson

Western Spring

June 26, 2015

Following hot on the heals of the Rachel Dolezal case we have been presented by the mass media with yet another story obviously designed to confuse people and blur our perception of the issues of race and ethnic identity, the case of Verda Byrd. Unlike Rachel Dolezal however, Verda Byrd is not a White woman pretending to be Black, she is described in the media as a ‘White woman’ who for seventy years believed she was Black.

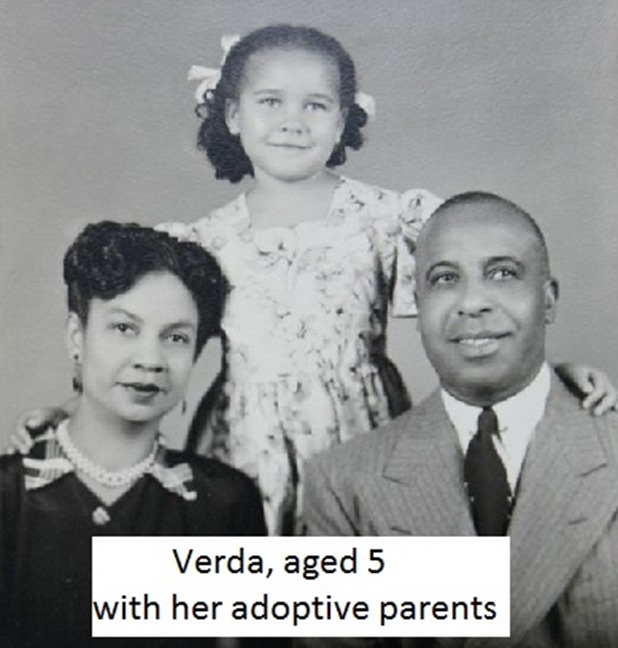

We are told in the various news media accounts that have been published that Verda Byrd was as a baby, first fostered and subsequently adopted by an ‘African-American’ couple, Ray and Edwinna Wagner, and was raised as a ‘Black child’, having been told by her adoptive parents that she was a ‘light-skinned African American’. Having lived as an ‘African American’ for most of her life, Verda decided at the age of seventy to begin tracing her biological parents and discovered they were both recorded as ‘White’. Subsequently, Verda has been re-united with three siblings, the only surviving children of her biological mother who had ten children in all.

Verda Byrd has been angered by the Rachel Dolezal case and has spoken out critically, as she feels that Dolezal has deceived people, claiming to be something she is not. This however causes us to examine Verda Byrd and her true racial status, as Byrd’s criticisms of Dolezal would appear to be misplaced if not hypocritical if she too were found to be claiming to be something she is not, and this issue of true racial status is brought sharply into question when one sees photographs of Byrd, who would appear to be of mixed race and not ‘White’ as she claims.

So, free from media hype and stories driven by an evident bias towards causing confusion over these issues, let us examine the facts of Verda Byrd’s background, just as we did regarding Rachel Dolezal, in my earlier article about her.

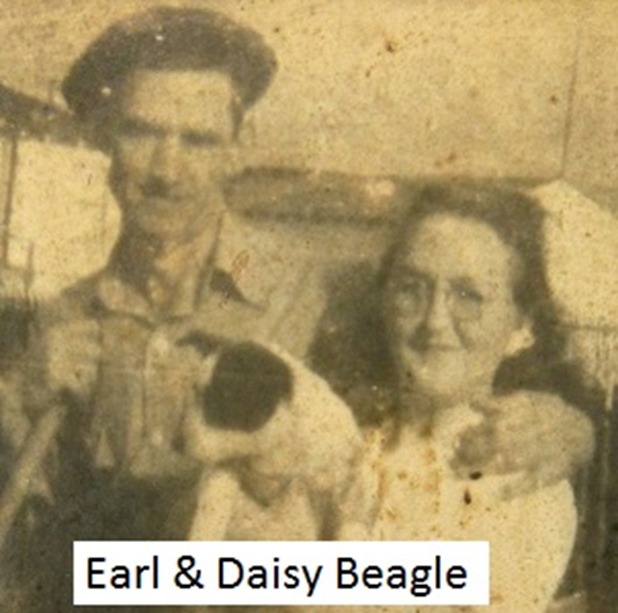

Verda Byrd was born Jeanette Beagle on 27th September 1942, apparently the fifth child born to a White couple, Earl and Daisy Beagle. Very shortly after Jeanette was born however, Earl Beagle walked out on his wife and never came back. It would appear that something significant had happened that motivated Earl Beagle to abruptly end his relationship with Daisy, the mother of his four other children, and sadly in February 1943, just months after Earl had walked out, Daisy was involved in an accident at work which left her hospitalised and unable to care for her children for many months. The children were all placed in care and while the older siblings were later returned to their mother, Jeanette who was still a baby and by this time had no memory of her biological mother, was deemed as too settled with her foster parents to have her life disrupted again. Daisy agreed to Jeanette’s adoption by the Wagners, who renamed her Verda and raised her as their adopted African American child.

If one examines photographs of Verda as a child, and as a young woman, she bears a striking similarity in appearance to her adoptive mother Edwinna Wagner, who was a ‘light-skinned African American’ woman and this was undoubtedly something that would have pleased Edwinna Wagner and been a significant factor in her decision to adopt Verda.

If one compares the photographs of Verda as a child and a young woman with a photograph of Earl and Daisy Beagle, it becomes apparent that she bears very little resemblance to either parent. We know that Daisy acknowledged Verda (Jeanette) as her biological child, but the obvious physical dissimilarity between Verda and Earl Beagle leads one to strongly suspect that he was probably not her biological father. For Verda to have the appearance of the ‘light-skinned African American’, one would logically expect her biological father to be a somewhat less lightly-skinned African American rather than the very European looking Earl Beagle.

In a report of this case in the San Antonio Express News, it states: “Interesting questions have been raised on the journey of self-discovery. One of Byrd’s sisters [presumably Sybil Panko] wondered whether their father was the same man. She noted Byrd seemed to have black features … [another sister, Kathryn Rouillard] said any concerns about Byrd’s heritage, or why Byrd was put up for adoption are a moot point …”

If one looks at a photograph of Verda Byrd with her three surviving siblings, it is evident that appearance wise, she is very much the odd-one-out. Sybil Panko, who is seventy-six years old and was evidently one of Earl and Daisy Beagle’s first four children, bears a strong similarity to her father, while Verda does not. The two younger siblings, Kathryn Rouillard, who is fifty-nine and Debbi Romero, who is fifty-six, resemble their mother and because of their ages, are obviously children that Daisy Beagle had much later with her second husband — her name was Daisy Pierce at her death.

The balance of probability therefore overwhelmingly suggests that Daisy and Earl Beagle had four children together and when Daisy became pregnant once again, eventually giving birth to Verda (Jeanette), Earl noticed the non-White appearance of the new baby and suspecting his wife of infidelity, walked out on her.

Once Daisy had recovered from the accident she later suffered, she regained custody of the four ‘legitimate’ children by her former husband, but was persuaded by social services to allow her ‘light-skinned’ but evidently mixed-race baby to be adopted by the Wagners. In race conscious 1940s America a White woman with four White children could still envisage finding a new husband, but a White woman with four White children and a mixed-race baby would have great difficulty finding a new husband, either Black or White.

While a comparative DNA analysis of Verda and her three half-sisters would be interesting to see, it seems virtually certain that Verda, a person of very dilute non-White ancestry, was correctly identified by her adoptive mother and is as she has always previously believed, a ‘light-skinned, African American woman’ — not the ‘White woman’ she now believes herself to be.