Ricardo Duchesne

Council of European Canadians

July 31, 2016

J.M. Bumsted claims that pre-1970s Canadians were “parochial” and closed-minded and that current SJWs students are the most educated “cosmopolitan” generation in human history.

The author of the most prominent survey of Canadian history in our universities, J.M. Bumsted, claims that “from the beginning” Canada was “a multiracial place, the destination of a constant flow of new immigrants of varying ethnicities.” But he knows full well that it was only after 1967/1971 that Canada began to accept non-White immigrants. The population that created Canada throughout much of its history was overwhelmingly White and mostly British in ethnicity and purely Quebecois in Quebec.

The discipline of history, uniquely nurtured by Europeans, requires one to be very attentive to what the sources say. On the issue of immigration, as we have seen in our Canada settlement series, Bumsted violates this most sacred principle of the historical profession. His objective in narrating Canada’s immigration history is to score ideologically on two fronts: on the one hand, he wants Eurocanadians students to believe that Canada was always “a veritable quilt of peoples and tongues” so that they take current mass immigration trends from the Third World as a natural feature of Canada’s long history, nothing to worry about; and, on the other, he wants to make them feel psychologically guilty for having ancestors who were racist and Anglocentric in prohibiting non-White immigration well into the 1960s, and in this way to induce them morally to accept their own dispossession by people who are very different racially and culturally.

Bumsted’s A History of the Canadian Peoples is quite blunt in its assessment of Canadians in 1945:

The Canadian government and the Canadian people were, by and large, exclusionist, racist, and not very humane in their attitudes towards immigration (p. 370).

He refers to a “Gallup poll in April of 1946” indicating “that two-thirds of Canadians opposed immigration from Europe” (p. 372), and to another poll a few months later in which Canadians ranked the “Japanese first and the Jews second” in response to the question, “what nationalities they would like to keep out of Canada?”

Canadians Were All “Racist” Before the 1970s

It is not just ordinary Canadians without a “proper” education who stand condemned before the altar of diversity today but every prominent member of the political elites before the 1960s. Here are some known expressions from the most educated politicians of the past. R.B. Bennett, Prime Minister from 1930 to 1935, told a British Columbia audience in 1907:

We must not allow our shores to be overrun by Asiatics, and become dominated by an alien race. British Columbia must remain a white man’s country (cited in Canada 1896-1921, A Nation Transformed, p. 68).

George Foster (1847-1931), who served in the cabinets of seven Prime Ministers, wanted “to keep British stock dominant.” Henri Bourassa, arguably the major politician of Quebec in the first four decades of the 1900s, told the House of Commons in 1904 that

it was never in the minds of the founders of the nation, it never was in the minds of the fathers of confederation…that in order to be broad…we ought to change a providential condition of our partly French and partly English country to make it a land of refuge for the scum of all nations (Ibid, p. 74).

Even the literary minded held similar views. Ralph Connor, author of the popular novel The Foreigner, published in 1909, envisioned Canada as a European melting pot:

Out of breeds diverse in traditions, in ideals, in speech, and in manner of life, Saxon and Slav, Teuton, Celt and Gaul, one people is being made. The blood strains of great races will mingle in the blood of a race greater than the greatest of them all (Ibid).

These attitudes continued well into the twentieth century. We have all read the statement of policy that Mackenzie King, Prime Minister of Canada, made before the House of Commons in 1947:

The people of Canada do not wish as a result of mass immigration to make a fundamental alteration in the character of our population. Large scale immigration from the Orient would change the fundamental composition of the Canadian population.

Canadians were in agreement with Mackenzie King through to the 1960s. Gallup polls in the 60s showed that only about one third of Canadians thought that Canada should bring any immigrants, and over 60 percent thought that the very low levels of Asian immigration (at the time) were already too high (Hawkins, 1991).

Racist ads 1950s portraying Canada as if it were beautifully White

Why Did Canadians Stop Being Racist in the 1970s?

So, why did Canadians suddenly agreed to open Canada’s borders to mass immigration from the Third World? How could an entire nation, from the people to the leaders, undergo such a dramatic change in attitudes within one generation? Bumsted actually addresses this question:

The conversion within the space of a single generation, from a very insular and parochial nation to one that was relatively sophisticated and cosmopolitan, much more capable of toleration of ethnic differentiation, has been one of the most remarkable and underrated public changes in Canadian history (p. 428).

But, clearly, the way he poses this change in attitude is extremely biased, and yet it is the standard answer in Canada today; Canadians in the past just didn’t know any better, they were too parochial; but thanks to a better education, more cosmopolitan surroundings, they learned the truth about the blessings of racial mixing and. He holds four factors responsible for nurturing a more “tolerant” Canada:

- WWII gave millions of Canadians “foreign experience” as soldiers spending years in Europe, 50,000 of whom married foreign girls.

- The very arrival of more than 3.5 million immigrants between 1946 and 1972, many of whom were neither British nor French, accustomed Canadians to people with different cultures, coupled with the fact that these immigrants came to live in cities rather than in isolated farmstead, mingling with each other and with traditional Canadians.

- The wave of modernization and urbanization that swept the country during these years; the world of electricity, machines stoves, refrigerators, radios, televisions and stereos all worked to create an urban, connected, cosmopolitan culture, dissolving the parochial attitudes of the past.

- Finally, Bumsted says, that the new communications media, particularly the rapid spread of television across the nation after 1950 “increasingly plugged Canadians into the world […] helped forced them out of their narrow insularity…into the international world previously beyond their ken” (p. 430).

We can hardly underestimate how influential this line of reasoning has been in portraying the diversification of Canada as a development led by people who are more open minded and educated than the previous “parochial” generations. Bumsted is voicing the view every ideologue of immigration expresses today in one way or another. It is incredible how much this argument has helped legitimate the current establishment, this whole idea that supporters of mass immigration are cosmopolitan characters with broad knowledge of the cultures of the world, humane and tolerant; whereas critics of mass immigration are limited in outlook, xenophobic for lack of knowledge of other cultures, leftovers from an insular past that no longer makes sense in our global age.

Yet, a far stronger argument can be made that Canadians, some of them, actually, changed their attitudes about Third World immigration during the 1970s only because they were compelled to do so without any open discussion and proper education. Canadians before the 1970s were not racist, but merely ethnocentric, that is, a people with a natural and normal preference for their own ethnic traditions. The research we have, based on objective assessment of the evidence, shows that ethnic groups throughout the world exhibit a preference for their own culture and a disposition to judge other cultures by their own standards. This preference is a healthy and practical evaluation of one’s ethnic identity and interests consistent with evolutionary theory and cultural sophistication.

Pre-1970s Canadians Were More Open-minded and Educated

Bumsted’s argument is contrived and illiberal. It does not allow for Canadians to express their natural ethnocentric attitudes but carries with it the clear threat of ostracism if they don’t blindly accept mass immigration and race mixing as a blessing. The argument is flawed to its very core. First, there is a clear time lag between the modernization wave Bumsted sees after WWII, in the 1950s, and the supposed change in attitudes of Canadians, which only came after the 1960s, since, as Bumsted himself notes, and as Gallup polls in the 1960s show, Canadians were still a “racist” lot well into the 1960s. The growth of large cities, which can be dated to earlier decades, and the spread of mass communication technologies, which were also quite evident from the 1920s onward, though these really spread in the 1950s, did not engender tolerant attitudes, it seems, on their own, or at least they took some time to have an effect on the minds of Canadians.

When this critical observation is connected to the very powerful fact that “tolerance” for diverse immigrants and prejudicial attitudes against minorities are still pervasive in hyper modern countries such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and in huge cities in China and India today, and, indeed, in all non-White modernized countries, we can see that there is a fundamental flaw in Bumsted’s standard argument. This argument presumes that racism declines as people of diverse ethnic backgrounds live together and “learn” from each other.

But the evidence we have so far is that only in the case of intra-European mixing do we have evidence of successful assimilation to a common “American” or “Canadian” culture. Canadians in the 1960s from different European backgrounds were well assimilated, despite their ethnic differences, to Canada’s Anglo heritage. Once we look at the data for black and White integration, in the case of the United States, for which we have the most data, or, for that matter, White and Indian integration in Canada, Australia, and the US, we find that tensions, ethnic segregation in places of living, where children go to schools, and in cultural activities, have not declined one bit, even though all blacks and Aboriginals now enjoy the same civic rights. The evidence shows, to the contrary, that the closer to each other different races live, the less tolerant they are of each other.

This leads me to another critical point; did Canadian attitudes really change with modernization, or was this change imposed from above by Canadian elites without democratic approval? Bumsted notes that by 1957 there were 44 radio stations and almost 3 million televisions in Canada. He also notes that in the 1940s and 1950s secondary education was extended to all, and that by 1961 there were nearly 4 million children in provincially controlled schools. Should we assume that these novelties in-and-of-themselves cultivated pro-mass immigration attitudes? Or should we wonder whether they were instead powerful tools of mass ideological indoctrination? Why only Western elites, not the elites of any non-Western modern country in the world, employed these new means of communication and universal education to portray their past as racist and in need of diversification?

We must reject completely the lie that pro-immigration individuals are tolerant, democratic, and worldly.

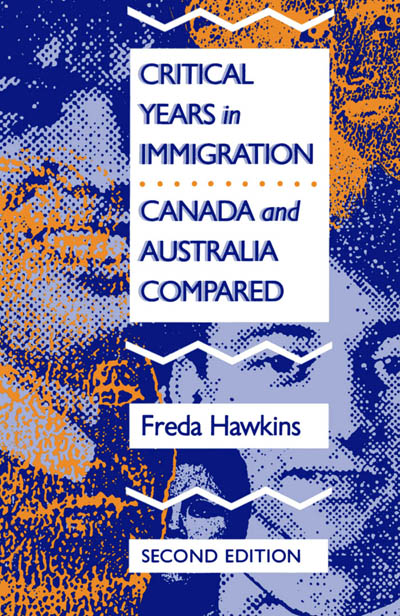

Fred Hawkins’s Critical Years in Immigration: Canada and Australia Compared (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991) informs us that the 1967 immigration regulations emphasizing skill and education, rather than racial origins, were not brought on by popular demand or even parliamentary debate and initiative, but by senior Ministers and Cabinet officials who “did not trust the average Canadian to respond in a positive way on this issue” (Hawkins, p. 63).

As noted above, Hawkins mentions Gallup polls in the 1960s showing that over 60 percent of Canadians thought that the very low levels of Asian immigration (at the time) were already too high. But in complete disregard to Canadian popular wishes, the borders of Canada were set wide open after to immigrants from Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, Central and South America and the Middle East, under the directives of all the major parties, the media, tenured academic radicals, and business elites.

How long will we go on insisting that rampant terrorism of Muslims in Western countries, the systematic raping of White girls by migrants, and the failure of black integration in the United States, are due to persistent White racism rather than a demonstration of the failure of multicultural and multiracial coexistence?

Why are these questions prohibited in our universities, the supposed centers of tolerance and cosmopolitanism? Why has the level of education declined across the West in the degree to which diversity has been promoted in the last few decades? The standard view Bumsted endorses is nothing but a mirage filled with self-induced deceptions and sheepish acquiescence to diversity ideology.