Diversity Macht Frei

January 20, 2017

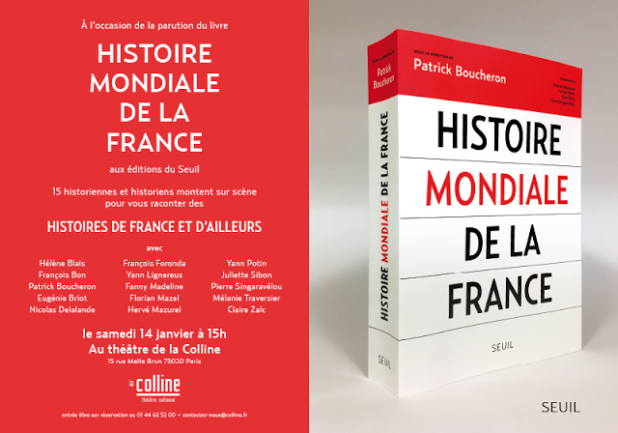

At the root of the genocide being inflicted on the European peoples through mass migration is an intellectual genocide that denies their existence as peoples – that is as ancestral communities of descent – by redefining their peoplehood in abstract and artificial terms. Much scholarly effort has been expended highlighting the role of foreigners in the various national histories of Europe’s peoples. The aim of this immense propaganda effort is to leave us with the impression that every European people that apparently exists is just an illusion, beneath which lies a mongrelised, hybridised, motley band of migrants, for whose blessings we should be pathetically grateful. A book has just been published in France that enshrines this style of genocidal history that denies the existence of a people: Histoire Mondiale de la France [Global History of France]. Here are some extracts from a review of it that appeared in Le Figaro.

From the first date, the mass is said: the history of France begins…before the history of France. 34,000 years before Jesus Christ! In the cave of Chauvet, in the time of Cro-Magnon “To neutralise the question of origins,” declares Boucheron without hesitation. “France before France that dissolves in the beginnings of a mixed and migrant humanity.”

Our “historians” thus give embodiment to the famous antiracist slogan of the 1980s: “We are all immigrants”. All migrants. All nomads. No races, no ethnic groups, no peoples. The proof from the void. We mustn’t stop there: before Cro-Magnon, there were our friends the Dinosaurs; and then further back the fish. Let us cherish our ancestors the fish!

In almost 800 pages and 146 dates, there is no deviation from the party line: everything coming from abroad is good. The barbarian invasions are “Germanic migrations”; the defeat of the Gauls allowed them enter into Roman globalisation; the Arab conquerors were much more brilliant than the pitiful Carolingian defenders; the Christian martyrs of Lyon came from elsewhere and Saint Martin was Hungarian. Christian theologians owe everything to the great Talmudist Rachi; the “shameful treaty of Troyes” of 1420 (which gave the kingdom of France to the English monarch) is a beautiful attempt to create perpetual peace through the union of crowns. Descartes is not the incarnation of French genius, but the “witness and actor of a Europe that is reconstituting itself and open to the world.” The navy of Colbert and Louis XIV owes it all to sailors born beyond our borders. Versailles is nothing but a mixture of Italian, Spanish, even English influences and the Thousand and One Nights are very French. Even the defeat in 1940 allowed the grotto at Lascaux to be discovered.

The ancient heroes taken from the “national legend”, as Boucheron says with disdain, are buffoons or failures. Nothing happened at Poitiers in 732 except the “illusion of an event”; and Charles Martel is just a “steward of the palace not even crowned surrounded by barons seated on enormous donkeys”. The theological criticism of Islam by Christianity is nothing but lies and exaggeration.

…Our historians, moulded by scientific rigour, in their own way reinvent providential history in the manner of Bossuet, but one in which the all-powerful and benevolent figure of God has been replaced by that of the Foreigner.

… We started with Cro-Magnon and we finish our grand journey with the tricolour flag. Our historians are not wrong: we will have the choice between the flag and the Chauvet cave; between a France rooted in its history, its culture, its civilisation and a return to the times of the great invasions. The millennial conflict between settled peoples and nomads. And that oh so French secular gulf between the Party of France and the Party of the Foreigner.

The author of the review, incidentally, is a Jew, Eric Zemmour, one of the few Jews I can think of who seems to have committed himself unreservedly to the non-Jewish people he lives among, although a residue of suspicion must always remain.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History