The New Observer

December 16, 2015

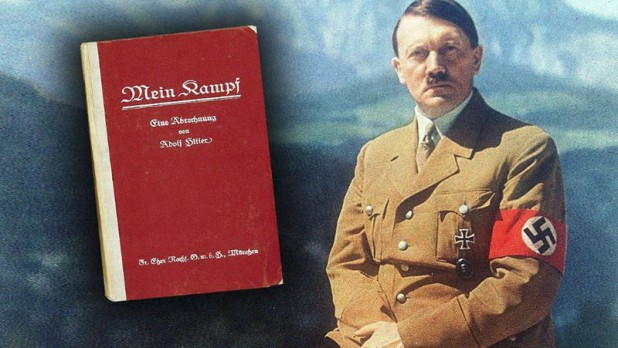

Some 4,000 copies of a heavily annotated Mein Kampf will legally appear in selected German bookshops on January 8, 2016, for the first time in 70 years—but after that the state will not be able to prevent anybody else publishing the work.

The Institute of Contemporary History (IFZ) in Munich, which has been hard at work preparing the “new” edition, titled Hitler, Mein Kampf. A Critical Edition, said it will contain 1,948 pages and will sell for €59, or around $62—an extravagant price which will do much to stifle its sales.

However, the official copyright on Mein Kampf in Germany expires at the end of 2015. Copyright to Hitler’s famous book passed to the state of Bavaria, which officially inherited all of his property in 1946, as he died without heirs.

The new version of Mein Kampf apparently contains the original German text, but each page is matched, almost paragraph by paragraph, by a facing page with no less than 3,500 “annotations.”

The purpose of these “annotations,” said an IFZ spokesman, is to “shatter the myth” surrounding the book.

This is somewhat of a bizarre claim, as there has never been any “myth” about the book, as anyone who has actually read it knows.

The book’s contents do not, as a recent edition of the sole originally authorized English edition noted, contain a “plan for world domination” or any other such nonsense.

Instead, it consists of a short autobiography, the effect of the First World War upon Germany, a discussion of race and the Jewish Question, the constitutional and social makeup of a future German state, and the early struggles of the NSDAP up to 1923.

The first five chapters are autobiographical in nature, dealing with Hitler’s personal life up to his service in the German army in World War I, ending with his temporary blinding by a British gas attack on the Western Front.

The next chapter deals with a discussion on the effectiveness of Allied War propaganda in the First World War, and a comparison with the German propaganda, which Hitler dismissed as a failure, and explained why.

The following two chapters are an eyewitness account of the Marxist-led revolution in Germany at the end of the War which led to the collapse of the German state and the Treaty of Versailles, and how Hitler was used by the German Army in 1919 to give political lectures for troops recently returned home. Then, a chapter explains how he was ordered by the Army to report on the tiny and ineffectual “German Labor Party”—and how he ended up being added to its membership without his consent.

From then on, the book is devoted to a description of the activities of the early period of the Nazi party, including the formation of the Brown shirts, the first meetings of the party, the violence perpetrated against the party by the Communists, and the internal structure of the party. The narrative ends just before the 1923 Putsch which saw him imprisoned.

Only one chapter, “Nation and Race” actually deals with his racial ideology in any real depth—out of a total of twenty-seven.

As can be seen, none of these topics are “mythical” in any sense of the word, and most of the work, which in normal “non-annotated” editions runs to less than 600 pages, is mainly of historical interest.

Nonetheless, Jewish groups in Germany have warned that the “book is dangerous and should never be printed again.”

Of course, the Internet and the free availability of the book in so many different formats has made a mockery of the German government’s censorship of the text.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History