Henry Dampier

March 22, 2014

The West is in a crisis surrounding a general collapse in social trust. Rather than focusing too much on the macro political situation, I would rather explore the consequences of this at the personal level.

Unlike when my grandfathers were working, or when my father worked, it is common for employees to distrust their bosses and their co-workers. There is no sense that the company exists for the long term benefits of its stake-holders. At a far lower level of technology and gross profitability, employees even at the lower level could expect to advance their careers within the same corporation for their entire lives. My grandfather was not an executive — he was a simple accountant at General Electric — but his retirement package ultimately made him a multimillionaire. He lived modestly for most of his life, did not work long hours, and raised two children.

Before the 1970s and after the collapse of the New Deal, it appeared for a brief time that norms supporting property rights had returned to the fore within American culture. The public culture was anti-Communist until the 1960s ran their course. The FBI under J. Edgar Hoover suppressed domestic left-wing factions until completely collapsing in the late 1960s. By the 1970s and Nixon’s resignation, the organized subversive left had achieved complete control over American institutions of cultural influence.

The 1945-1972 era was a brief interlude during which the left regrouped as public cooperation with the Soviet Union became illegal. In 1971, Nixon severed the last link with the gold standard, and the great inflation of the 1970s combined with the collapse in public order demolished general social trust.

This was the time when many of today’s baby boomers came of age — during a time of cultural confusion and economic chaos. The inflation destroyed many poorer families, and created a new class of hyper-corporate ‘yuppies’ that took their place. While apologists will tend to say that the yuppies were just ‘better’ than the people who came before them, in reality they were just better at getting the freshly-printed greenbacks than their more sluggish brothers and sisters.

The post-1970s showed that hard work does not pay, because property rights are not secure. What does pay is to be a corrupt oligarch, to divorce using lawyers to loot your family, or to be a canny speculator.

Due to continual inflation, workers lose out in a systematic way to capital, who have superior social and financial connection to the apparatus that creates new money. Merit in actual market production becomes socially déclassé, because, in nominal terms, it is much less valuable than finagling access to unlimited credit or speculating based on superior access to information and superior execution speed on the markets.

America is not a good place to build a factory because property rights for factory owners are insecure. If you build a factory, dozens of investigators will descend upon your operation, guided by a domestic intelligence agency called a newspaper, to impede your ability to run your business.

In China, by contrast, property rights may be contingent upon approval by the state, but it is a clearer binary. If you cease to be protected by a political master, you will be executed. It is a more clear cut and honest tyranny. There is the Party and the military, and perhaps some informal crime, but it is at least a little more predictable.

In the United States, you can be looted by a panoply of government agencies, ‘nonprofits,’ legal firms, angry business associates, employees, and wives. The ever expanding legal code provides infinite pretexts for depriving you of your property.

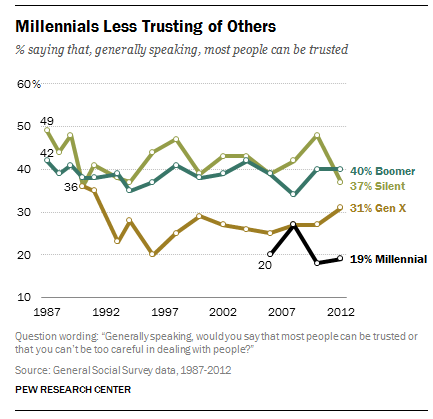

It is for this reason, perhaps, that social trust has declined as each of the new (still-living) generations has come of age:

To maintain large institutions of any kind, social trust is crucial. It’s common to read comments and blog posts by dissatisfied employees who no longer trust their bosses, and by bosses who do not believe that their employees are trustworthy.

A large part of this owes to diversity of gender, race, and religion: it is not even really possible for people from foreign cultures to partake in social trust building rituals that are culture-bound properly.

Asians and Europeans don’t drink the same kinds of alcohol and have wildly differing tolerance levels. They do not have the same mannerisms even after a generation of Westernization. Indians have a complex set of relations to one another that are completely opaque to Europeans who aren’t steeped in their culture. A competent manager at handling Indian teams going to struggle in leading Europeans, even if he’s de-racinated.

This is something openly acknowledged even in publications like the Harvard Business Review: there is no human resources department on the planet that will not say that ‘diversity is a challenge.’ They will not acknowledge, however, that it is a cost that tends to have questionable benefits, and usually results in increased risks of project failures. The biggest diversity problem of all is the mixture of men and women within companies: women simply do not have the same social incentive structure as men do. Attempting to integrate the genders has resulted in an unprecedented drop in the male labor force participation rate.

While the statistics are undisputed by the ‘responsible’ experts, there is almost no acknowledgment in the respectable press of the obvious solution to this social problem. This makes the educated consensus a brittle one. America’s elite class can either accept Soviet-level stagnation and the humiliation that comes with that, or they can capitulate to reality. It is clear that, at present, they prefer to maintain the lies at enormous cost to the general public.

Pew attempts to spin the declining trust in saying that Millenials are also far more ‘optimistic’ about the future. However, without trust, there is no future worth living in.