Stuff Black People Don’t Like

October 18, 2015

Wikipedia tells us the Butler-Tarkington community in Indianapolis was exclusively white until the mid-1950’s when black people began to integrate the neighborhood. Today, the Fox affiliate in Indianapolis noted the exclusively black violence in Butler-Tarkington community in Indianapolis has one black resident feeling like he is living in “one of those countries with ISIS in it.”

When the community was all-white, did competing gangs have to call a “truce” so the wanton killing would stop?

No.

Not at all.

But that’s what has happened in 2015, as the black population is rising and the violence is increasing. [Truce declared in north side Indianapolis murder zone, Fox 59 Indy, 10-15-15]:

Four bodies have fallen on the south side of the Butler-Tarkington community since early August.

One of the dead was a 10-year-old boy. The most recent, Malik Perry, 19, was found in an alley west of 41st Street and Byram Avenue Tuesday night.

A group of older neighbors, they refer to themselves as OGs, Original Gangsters, due to their longtime residence and sometimes shaky pasts, have joined forces to become WADE, Working Against Devils Every day. They told Fox 59 News they have been successful in negotiating a ceasefire in the trouble-plagued area.

“It’s going back and forth, this area with another area, ‘You take one of mine, I take one of yours.’ It’s gotten too far out of hand, way out of hand,” said Anthoney Hampton as he walked the alley where Perry died. “I had a chance to talk with one of the older guys from the other area that has a lot to do with these homicides and we came to a truce. He spoke to his younger guys over there, told them enough is enough. I’ve reached out to a couple guys that are a couple years younger than me and talked to the younger guys, I’ve reached out to the family members in the area to talk to the guys, and I’ve had guys calling from prison and saying this has to stop, enough is enough.”

The truce Hampton brokered was confirmed by the leader of one of the rival crews who told Fox 59 News that contrary to the theories of IMPD investigators, the recent bloodshed stemmed from a fight on the midway of the Indiana State Fair that left an Indiana State trooper injured in August, about the time the tit-for-tat shootings began.

“We’re hoping that it lasts forever,” said Hampton. “We’re hoping that the loss of this young man’s life is enough. We can only take it day-by-day of course.”

Day-by-day may be enough if WADE can walk the pavement north of 38th Street and West of Illinois Street until Sunday when a peace rally encompassing the entire community will be held in Butler-Tarkington Park.

“Well, we do definitely need the people of the northside of the Butler-Tarkington community,” said Damon Lee. “We are all one neighborhood. The neighborhood, they are all involved in it, too, and the crime is starting to inch closer to their side of the neighborhood. We’re right across the street from them, so it is time for them to step up to the table and join us.”

Construction is already underway on a $5 million park upgrade.

“We have to do something and we have to do it now. It seems like every time we have a newscast, someone else dies,” said Wallace Nash who called for a recreational center to be built to provide year round activities for the neighborhood children. “And give them something good and positive. You are a product of your environment. If this is all they see then this is all they’ll be.”

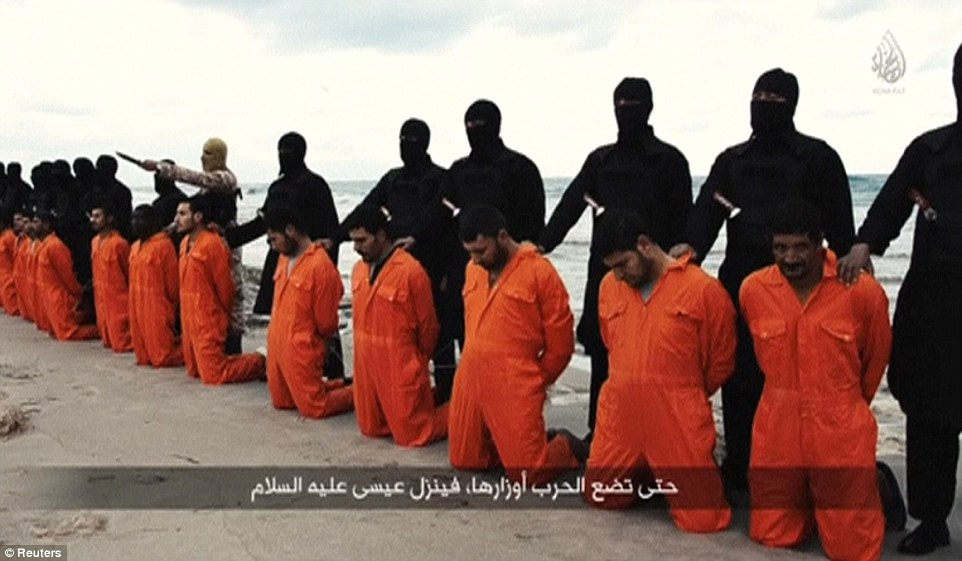

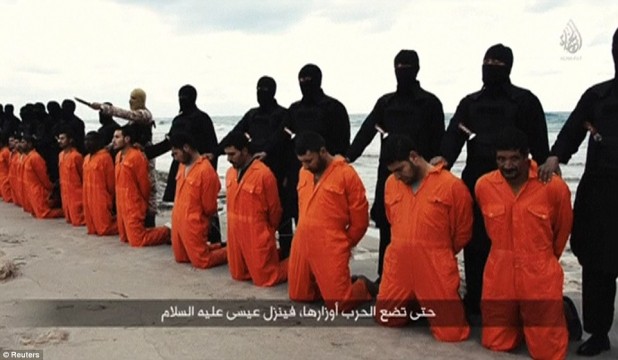

Hampton said he feels like he’s living in, “one of those countries with ISIS in it,” where killing seems wanton.

“I had a young lady tell me like there’s not enough alpha males to deal with these young wolves,” said Hampton.

The houses from when the community was all-white (and virtually crime-free) remain, but the community is far, far different than it was when only white people called the area home. [Butler Tarkington: A diverse, divide, IndianapolisNewsBeat.com, May 27, 2014]:

Marnie Robinson crosses into the southern side of Butler Tarkington on her bus ride to work at the Subway on 38th Street. At the bus stop people panhandle and ask her for money. This happens often.

She arrives at Subway and the work day is busy. Many customers are in and out of the restaurant. Eventually she and her coworker get a break when the rush diminishes about five minutes before close.

But then a new customer appears. He is wearing a hoodie and a backpack.

He also holds a gun.

The man asks for the money in the register and Robinson’s body shakes with fear while trying to get it open. She hands the man the money, but he asks about the company’s safe. She explains that she cannot get into the safe.

The man then tells Robinson and her coworker to go to the back of the restaurant and count to 10. They do, and when they return to the front of the restaurant the man is gone.

“The robbery woke me up,” said Robinson about the incident. “This area is dangerous, but this kind of stuff happens everywhere.”

Crimes such as what Robinson experienced, along with abandoned housing and social differences from the area’s diversity, each contribute to a potential split that residents have come to see in the Butler Tarkington neighborhood.

Considering its history, Butler Tarkington has grown to be racially diverse.

The neighborhood used to house mostly white, middle-class residents in the early to mid-1900s, according to The Polis Center’s website.

But after various civil rights movements, the African-American population increased tenfold. This change was due to the opening of neighborhoods to different races.

“I think there is a long history of diversity in the neighborhood,” Feeney said. “That’s the reason the neighborhood association was formed, to navigate through different people coming together.”

Now only about 65 percent of the population is Caucasian, according to the U.S. Census data via SAVI.

Nearly a third of the neighborhood is African-American, and about 5 percent of residents are of multiple races.

This diversity is a reason that some residents move to the neighborhood.

“It is important that there is diversity in the neighborhood,” Feeney said. “The location, being right smack-dab in the middle of Indianapolis, makes Butler Tarkington a perfect place to live, and it will pull from all different parts of our community.”

Though the different types of people in the neighborhood seem to coexist, some onlookers describe an imaginary divide between the north and south sides of Butler Tarkington.

“For years there was what they called, North Butler Tarkington and South Butler Tarkington,” said Monroe Gray, a Democratic city-county councilman for the 8th District, which includes the neighborhood. “They are kind of like oil and water. They don’t really mix.”

This figurative dividing line lies approximately around 44th Street.

South of this road to 38th Street is an area of escalated crime, according to Indianapolis Metropolitan Police crime statistics on its site’s crime viewing application.

This story is proof of why restrictive covenants and segregation existed: to keep once thriving white communities from becoming food deserts where black violence leaves residents thinking they live in ““one of those countries with ISIS in it.”