The New Observer

February 18, 2016

Bust of Queen Nefertiti, 1370–1330 BC, wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Amazingly enough, some claim she was black.

February is officially “Black History Month” in America, Britain, and Canada, and it is now commonplace during this month to recycle stories about past “great black civilizations” and “black inventions”—except, as demonstrated below, these claims are all mythical.

The most widely heard claim of a great “past black civilization” is that of ancient Egypt, because of the existence of a number of black, or “Nubian,” pharaohs.

The facts of the matter are as follows: ancient Egypt was founded in 3300 BC, and the Nubians ruled only for a short period between 732 and 664 BC.

This was more than two thousand years after ancient Egypt had been founded—and, significantly, the black ascendancy to the throne marked the collapse of Egypt, not its foundation.

In reality, as demonstrated in the profusely illustrated full-color book, The Children of Ra: Artistic, Historical, and Genetic Evidence for Ancient White Egypt, the founders of ancient Egypt were of European racial stock.

Although blacks and Semites were present in small numbers at the early stages of ancient Egypt’s history, they only featured as trading partners, slaves, or hired mercenaries.

Above, left: Yuya, an Egyptian nobleman from 1400 BC. He was the father of Tiy, the wife of Pharaoh Amenhotep III. Yuya’s blond hair has been well preserved by the embalming process. Alongside, his equally blonde-haired wife, Thuya, great grandmother of Tutankhamen. From The Children of Ra.

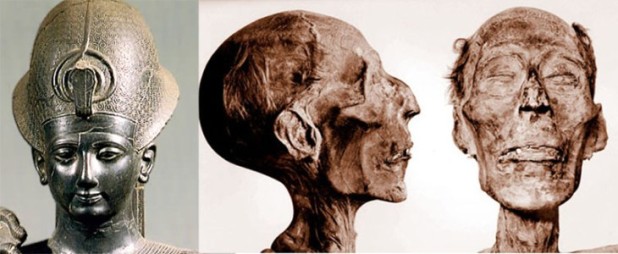

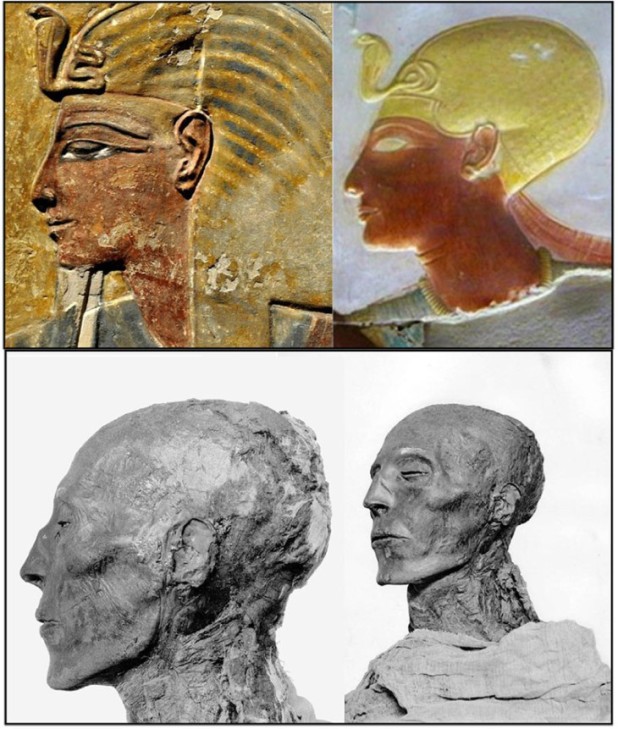

Above: A statue of Ramesses II, nineteenth dynasty (1292–1225 BC), and his mummy. From The Children of Ra.

Above: A bust of the female Pharaoh Hatshepsut, fifth pharaoh of the eighteenth dynasty (1509–1458 BC), and her mummy. From The Children of Ra.

Above: Artwork depicting Pharaoh Seti I, made during his lifetime at the Temple at Abydos, circa 1320 BC, and his mummy. From The Children of Ra.

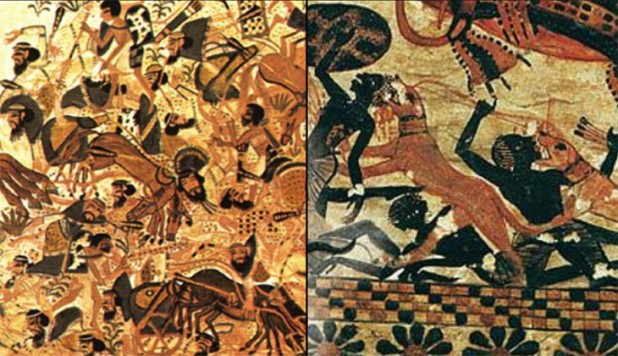

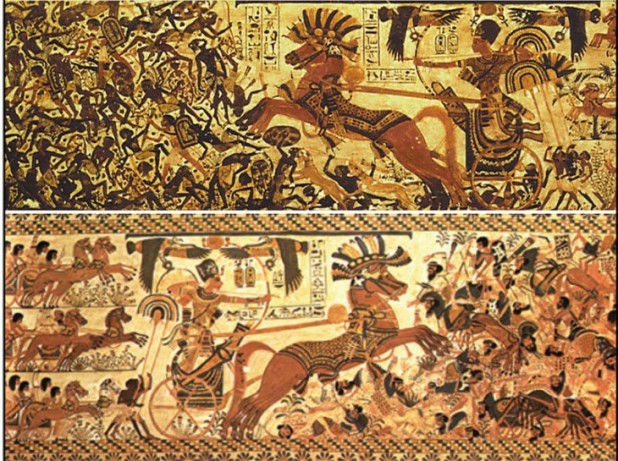

Above: Close-ups of the sides of Tutankhamun’s “Hope Chest” showing Semitic and black enemies being defeated. From The Children of Ra.

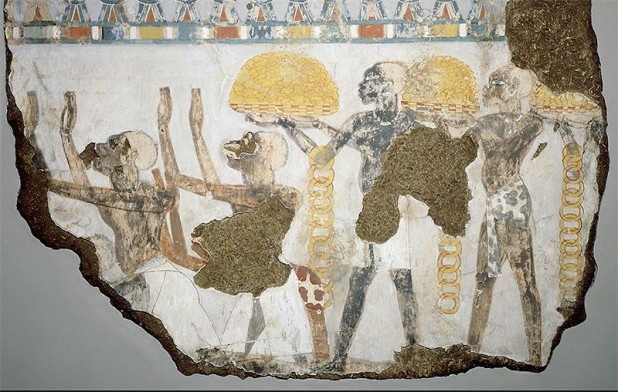

Above: Nubians bringing tribute to the pharaohs, Tomb of Sobekhotep, twelfth dynasty, circa 1850 BC. From The Children of Ra.

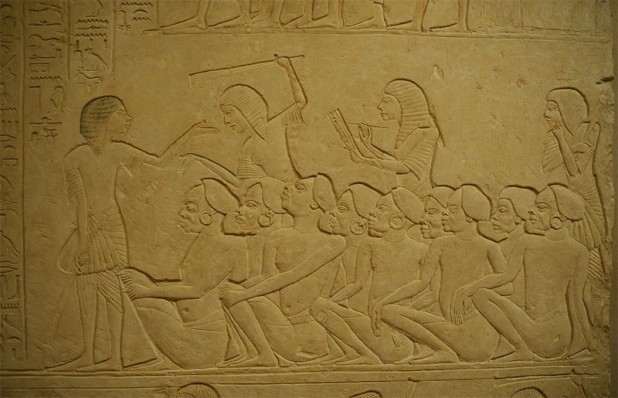

Above: Egyptian slave market, with black slaves waiting to be sold. Bologna Museum. From The Children of Ra.

In addition, the white Egyptians left many written references to the black population in Nubia, and in their own country. The most complete record and translation of these scripts was undertaken by Professor James Henry Breasted, Professor of Egyptology and Oriental History in the University of Chicago in his worksHistory of Egypt, from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, and his Ancient Records of Egypt series.

The ancient Egyptians invaded Nubia several times, and the final conquest of that land was attained by Sesostris III in 1840 BC. As translated by Breasted, the first Semneh stela inscription recounting the subjugation of Nubia by Sesostris III reads as follows:

“Southern boundary, made in the year 8, under the majesty of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Sesostris III . . . in order to prevent that any black should cross it, by water or by land, with a ship, or any herds of the blacks; except a black who shall come to do trading in Iken, or with a commission. Every good thing shall be done with them but without allowing a ship of the blacks to pass by Heh, going downstream, forever.”

More transcripts and illustrations are available online here.

By the time of the twenty-fourth dynasty, about 730 BC, Egypt’s population resembled that of today: a mixed-race mass made up of white, Semitic, and black extraction.

In 727 BC, the Nubian king Piye invaded Egypt and established the twenty-fifth dynasty. This era was the first genuinely black rule in Egypt, and although the twenty-fifth dynasty is counted as part of the historical line of rulers of Egypt, it had no links at all with the earliest kings—and founders—of that civilization.

This Nubian dynasty came to an abrupt end when Egypt was invaded by the Assyrians in 655 BC, only some 72 years later.

The Afrocentrist claim that the handful of black pharaohs from the twenty-fifth dynasty “proves” that ancient Egypt was African in origin is as false as claiming that the United States of America was founded by blacks because it had a half-black president in 2011—or that Detroit was founded by blacks because it has a majority black population in 2015.

In fact, as the historical record shows, the appearance of blacks as “pharaohs” marks the end of ancient Egypt, not its foundation.

It is not only in ancient history where these “black history” myths are propagated. Every February, the public is treated to a large number of claims about “black inventions” as well.

The most prominent of these claims are briefly discussed hereunder.

Myth 1: Filament for lightbulb.

The claim: Lewis Latimer invented the carbon filament in 1881 or 1882.

The truth: English chemist/physicist Joseph Swan experimented with a carbon-filament incandescent light in 1860, and by 1878 had developed a better design which he patented in Britain.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Thomas Edison developed a successful carbon-filament bulb, receiving a patent for it (#223898) in January 1880. From 1880 onward, countless patents were issued for innovations in filament design and manufacture (Edison had over 50 of them).

Neither of Latimer’s two filament-related patents in 1881 and 1882 were among them, nor did they make the lightbulb last longer, nor is there reason to believe they were adopted outside Hiram Maxim’s company where Latimer worked at the time.

Myth 2: The artificial heart pacemaker control unit.

The claim: Invented by Otis Boykin.

The Truth: Boykin did develop his own control unit for the artificial heart pacemaker, but this was not an innovation, merely an improvement upon the already existing pacemaker, which had first been developed in 1926, by Dr. Mark C. Lidwill of the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital of Sydney, Australia. Without the prior development of the pacemaker, Boykin’s improved control unit would never have come about.

Myth 3: The fireproof safe.

The claim: Invented by Henry Brown in 1886.

The truth: Strongboxes had been around since at least 1835, when English inventors Charles Chubb and Jeremiah Chubb took out a patent for a fireproof safe. Brown’s “invention” consisted of dividing the interior of a strongbox into compartments to hold documents.

Myth 4: The multiplex telegraph.

The claim: Invented by Granville T. Woods.

The truth: The earliest patents for train telegraphs go back to at least 1873. Lucius Phelps was the first inventor in the field to attract widespread notice, and the telegrams he exchanged on the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad in January 1885 were hailed in the Feb. 21, 1885 issue of Scientific American as “perhaps the first ever sent to and from a moving train.”

The claim: Invented by Gerald A, Lawson in 1976.

The truth: Gerald Lawson worked as director of engineering and marketing for Fairchild Semiconductor’s video game division, and oversaw the production of the Fairchild Channel F video game console, which was the main competitor to the Atari system. However, Lawson’s contribution was only possible by him using the 8-bit microprocessor Fairchild F8 Central Processing Unit (CPU), developed by white engineers at the Fairchild Company. Without disparaging Lawson’s design capabilities, it can be asserted that without the F8 CPU, the gaming unit would never have been created.

Myth 6: Laser cataract surgery.

The claim: Patricia Bath “transformed eye surgery” by inventing the first laser device to treat cataracts in 1988.

The truth: Use of lasers to treat cataracts in the eye began to develop in the mid-1970s. M.M. Krasnov of Russia reported the first such procedure in 1975. One of the earliest US patents for laser cataract removal (#3,982,541) was issued to Francis L’Esperance in 1976.

In later years, a number of experimenters worked independently on laser devices for removing cataracts, including Daniel Eichenbaum, whose work became the basis of the Paradigm Photon™ device; and Jack Dodick, whose Dodick Laser PhotoLysis System eventually became the first laser unit to win FDA approval for cataract removal in the United States.

Myth 7: 3-D graphics technology used in films.

The claim: Invented by Marc Hannah in 1982.

The truth: Although Hannah is a specialist in developing the computer hardware which filmmakers and others use to create 3-D graphics, the actual company for which he works, Silicon Graphics, Inc. (SGI), was founded in 1981 by Jim Clark, whose research work in computer graphics led to the development of systems for the fast rendering of three-dimensional computer images.

Myth 8: The gas mask.

The claim: Invented by Garrett Morgan in 1914.

The truth: The invention of the gas mask predates Morgan’s breathing device by several decades. Early versions were constructed by the Scottish chemist John Stenhouse in 1854 and the physicist John Tyndall in the 1870s, among many other inventors prior to World War I.

Myth 9: The traffic signal.

The claim: Invented by Garrett A. Morgan in 1923.

The truth: The first known traffic signal appeared in London in 1868 near the Houses of Parliament. Designed by J.P. Knight, it featured two semaphore arms and two gas lamps. The earliest electric traffic lights include Lester Wire’s two-color version set up in Salt Lake City circa 1912, James Hoge’s system (US patent #1,251,666) installed in Cleveland by the American Traffic Signal Company in 1914, and William Potts’ 4-way red-yellow-green lights introduced in Detroit beginning in 1920. New York City traffic towers began flashing three-color signals also in 1920.

Garrett Morgan’s cross-shaped, crank-operated semaphore was not among the first half-hundred patented traffic signals, nor was it “automatic” as is sometimes claimed, nor did it play any part in the evolution of the modern traffic light.

Myth 10: Peanut butter.

The claim: Invented by George Washington Carver in 1903.

The truth: Peanuts, which are native to the New World tropics, were mashed into paste by Aztecs hundreds of years ago. Evidence of modern peanut butter comes from US patent #306727 issued to Marcellus Gilmore Edson of Montreal, Quebec in 1884, for a process of milling roasted peanuts between heated surfaces until the peanuts reached “a fluid or semi-fluid state.” As the product cooled, it set into what Edson described as “a consistency like that of butter, lard, or ointment.”

Myth 11: The blood bank.

The claim: Created by Dr. Charles Drew in 1940.

The truth: During World War I, Dr. Oswald H. Robertson of the US army preserved blood in a citrate-glucose solution and stored it in cooled containers for later transfusion. This was the first use of “banked” blood.

By the mid-1930s the Russians had set up a national network of facilities for the collection, typing, and storage of blood. Bernard Fantus, influenced by the Russian program, established the first hospital blood bank in the United States at Chicago’s Cook County Hospital in 1937. It was Fantus who coined the term “blood bank.”

Myth 12: Washington DC city plan.

The claim: The city was designed and laid out by Benjamin Banneker.

The truth: Pierre-Charles L’Enfant created the layout of Washington DC. Banneker assisted Andrew Ellicott in the survey of the federal territory, but played no direct role in the actual planning of the city.

Myth 13: The air brake/automatic air brake. The claim: Invented by Granville Woods in 1904.

The truth: In 1869, a 22-year-old George Westinghouse received US patent #88929 for a brake device operated by compressed air, and in the same year organized the Westinghouse Air Brake Company.

Myth 14: The air conditioner. The claim: Invented by Frederick Jones in 1949.

The truth: Dr. Willis Carrier built the first machine to control both the temperature and humidity of indoor air. He received the first of many patents in 1906 (US patent #808897, for the “Apparatus for Treating Air”). In 1911 he published the formulae that became the scientific basis for air conditioning design, and four years later formed the Carrier Engineering Corporation to develop and manufacture AC systems.

There are many more such examples, but the topic would become tedious.

It is furthermore unlikely for Africa to have produced any inventions or advances at all, given that the average sub-Saharan African IQ ranges between 60 and 80. According to the internationally-accepted Sanford Binet intelligence scale, an IQ of 80 to 89 is regarded as “dull.”

Finally, as pointed out in the book Race by Oxford University’s Professor John Baker, the wheel was unknown in sub-Saharan Africa even in the mid-1800s. Baker quotes the explorer Dr. David Livingstone’s diaries which describe the Africans in the village of Linyanti, in present-day Namibia, as turning out in their thousands to see his “vehicles in motion and thus for the first time to observe the rotation of a wheel” (Chapter 19: The Negrids II. Foreign influences on culture, Race, Prof. John Baker).

Finally, as pointed out in the book Race by Oxford University’s Professor John Baker, the wheel was unknown in sub-Saharan Africa even in the mid-1800s. Baker quotes the explorer Dr. David Livingstone’s diaries which describe the Africans in the village of Linyanti, in present-day Namibia, as turning out in their thousands to see his “vehicles in motion and thus for the first time to observe the rotation of a wheel” (Chapter 19: The Negrids II. Foreign influences on culture, Race, Prof. John Baker).

To believe that a people who, only 170 years ago, did not have the wheel, could produce ancient civilizations and invent modern machinery, beggars belief.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History