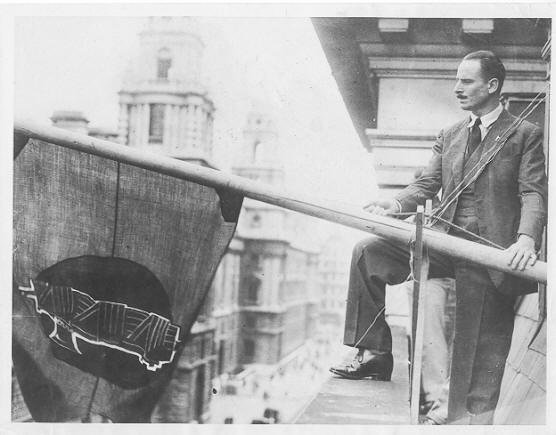

Oswald Mosley

May 31, 2015

Our opponents allege that Fascism has no historic background or philosophy, and it is my task this afternoon to suggest that Fascism has roots deep in history and has been sustained by some of the finest flights of the speculative mind. I am, of course, aware that not much philosophy attaches to our activities in the columns of the daily press. However, I trust you will believe that those great mirrors of the public mind do not always give a very accurate reflection, and while you only read of the more stirring moments of our progress, yet there are other moments, which have some depth in thought and constructive conception.

I believe that Fascist philosophy can be expressed in intelligible terms, and while it makes an entirely novel contribution to the thought of this age, it can yet be shown to derive both its origin and its historic support from the established thought of the past.

In the first instance, I suggest that most philosophies of action are derived from a synthesis of cultural conflicts in a previous period. Where, in an age of culture, of thought, of abstract speculation, you find two great cultures in sharp antithesis, you usually find, in the following age of action, some synthesis in practice between those two sharp antitheses which leads to a practical creed of action.

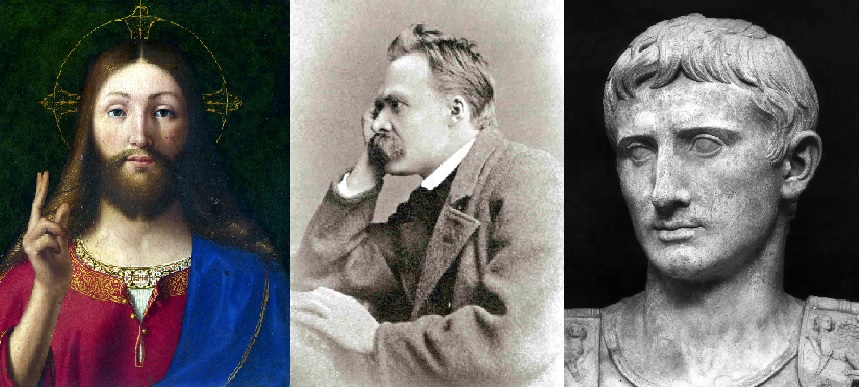

I would suggest to you that in the last century, the major intellectual struggle arose from the tremendous impact of Nietszchian thought on the Christian civilisation of two thousand years. That impact was only very slowly realised. Its full implications are only today working themselves out. But turn where you will in modern thought, you find the results of that struggle for mastery of the mind and the spirit of man. I am not myself stating the case against Christianity, because I am going to show you how I believe the Nietszchian and the Christian doctrines are capable of synthesis.

On the one hand you find in Fascism, taken from Christianity, taken directly from the Christian conception, the immense vision of service, of self-abnegation, of self-sacrifice in the cause of others, in the cause of the world, in the cause of your country; not the elimination of the individual, so much as the fusion of the individual in something far greater than himself; and you have that basic doctrine of Fascism, service, self-surrender to what the Fascist must conceive to be the greatest cause and the greatest impulse in the world. On the other hand you find taken from Nietszchian thought the virility, the challenge to all existing things which impede the march of mankind, the absolute abnegation of the doctrine of surrender; the firm ability to grapple with and to overcome all obstructions. You have, in fact, the creation of a doctrine of men of vigour and of self-help which is the other outstanding characteristic of Fascism.

At the moment of a great world crisis, a crisis which in the end will inevitably deepen, a movement emerges from a historic background which makes its emergence inevitable, carrying certain traditional attributes derived from a very glorious past, but facing the facts of today, armed with the instruments which only this age has ever conferred upon mankind. By this new and wonderful coincidence of instrument and of event the problems of the age can be overcome, and the future can be assured in a progressive stability. Possibly this is the last great wave of the immortal, the eternally recurring Caesarian movement; but with the aid of science, and with the inspiration of the modern mind, this wave shall carry humanity to the further shore.