Duluth News Tribune

February 9, 2015

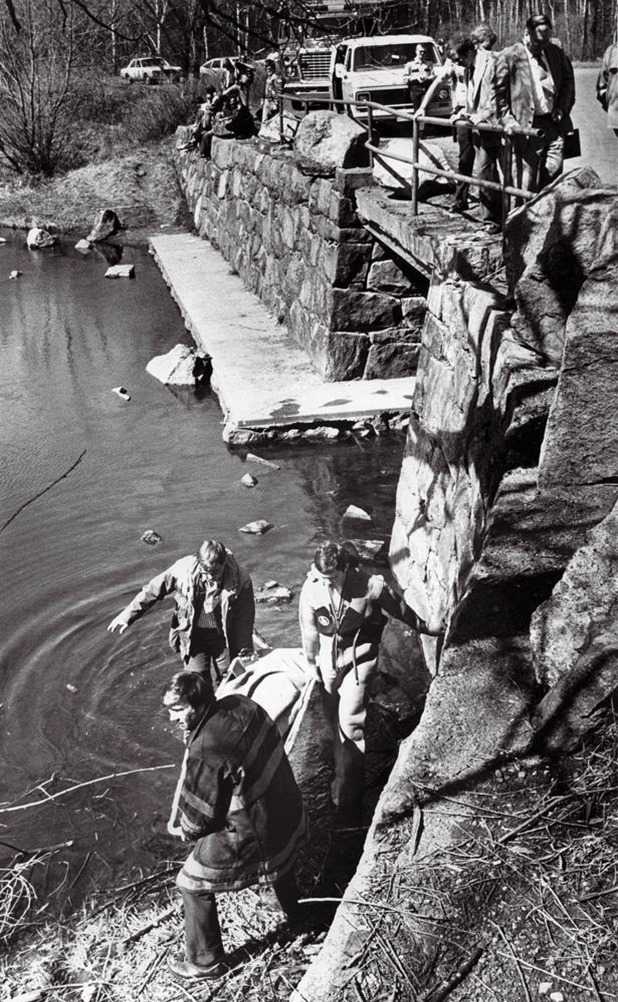

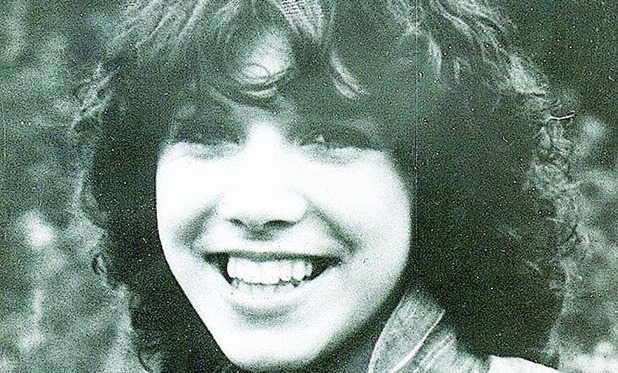

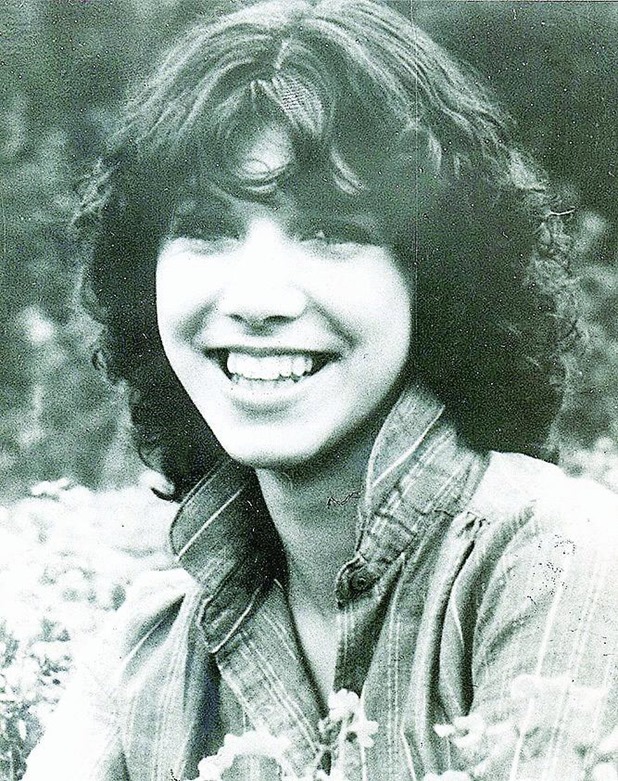

Carrie Andrew’s body was found facedown, partially submerged in Twin Ponds near Enger Park on May 6, 1981. She had died of a single small-caliber bullet to her head.

A passerby spotted her body about 2:15 p.m. that day about 15 feet below Skyline Parkway. It remains unknown how long her body lay in the water — she was last seen at about 8 p.m. the day before.

Andrew’s parents reported that she had left their Farley Lane residence on the evening of May 5 to walk to the nearby Ridgeview Lanes bowling alley, where she was to meet some friends. She was last seen by two friends walking on Calvary Road toward the bowling alley.

Andrew graduated from Duluth East High School in January 1981, having completed her coursework early, and was planning to take part in the spring commencement ceremony, according to newspaper accounts at the time. She had taken a modeling course at a Twin Cities school that winter and did some work modeling clothes at the Miller Hill Mall.

Her sudden and unexplained death led to days of front page headlines as investigators struggled to develop leads and conduct interviews with anyone who knew her.

There was no evidence that she had been sexually assaulted, and it did not appear that she had put up a fight before being shot.

“She certainly didn’t expect to be killed,” Detective Inspector Ernest Grams said in a 1981 News Tribune story. “She didn’t have an opportunity to defend herself.”

Evidence submitted to the BCA at the time also failed to uncover any new information. Police even drained the ponds in the weeks after her body was discovered in a fruitless effort to uncover any useful information.

Over the years, investigators conducted hundreds of interviews and followed hundreds of leads. Duluth Police Chief Gordon Ramsay credited the collaborative effort of the two agencies in finally cracking the case.

“It’s the relationship that we have with the BCA and the good work that was done early on in this case that brings it to an end,” he said. “We’re proud of where we are today.“

DNA technology credited

If not for significant advances in DNA technology over the past three decades, investigators said the case would probably remain unsolved.

Over the years, BCA forensic scientists continued to work with DNA that was recovered from Andrew’s body, eventually tracing it back to a male subject. Using databases of criminal offenders, scientists continued to search for a match to the DNA.

“It was clear that the person who left this DNA at the scene was not in any of the convicted offender databases that we were able to search,” said Catherine Knutson, director of BCA Forensic Science Services.

Then the big break came in March 2014.

Using new technology, investigators found a partial match between the DNA sample and an offender in the system. Testing indicated that the man who provided the sample was closely related to the man whose DNA was found on Andrew’s body.

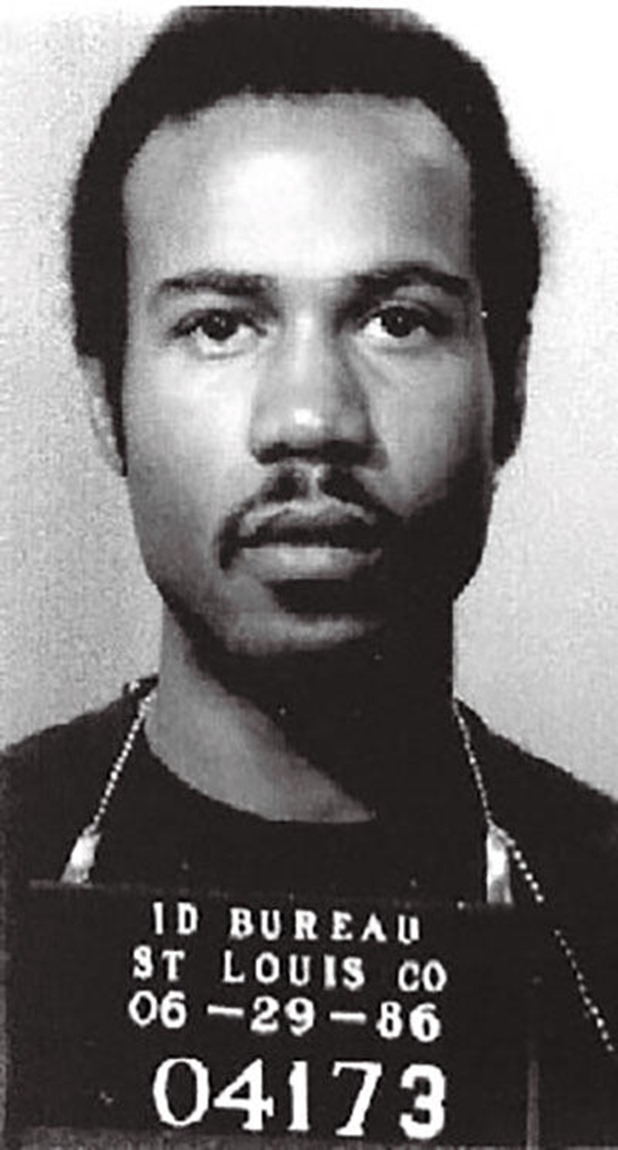

It turned out that offender in the DNA database was Cecil Oliver’s son.

Oliver died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound in Chicago in 1988 at the age of 30. At the request of local officials, authorities in Chicago recently obtained a DNA sample from his remains.