Steve Sailer

VDARE

March 10, 2015

If you’ve been, say, setting a world record for spelunking since August 14, 2014 and only recently resurfaced, you may have been surprised to find the Obama Administration and the media still worked up over Ferguson, MO. Even odder, although all goodthinkers everywhere remain in a fury at Ferguson, the justification has switched from White Racist Cops Murdering Black Babies Bodies in Cold Blood to … speed traps.

Reader X has written an analysis for me of the actual stats on traffic stops (please note that everything below in this post is by Reader X):

IS THE FERGUSON POLICE DEPARTMENT A RACIST OUTLIER AMONG POLICE AGENCIES?

No, Ferguson is not an outlier, at least not by this fundamental metric commonly used by academics, legislators and federal officials. The Disparity Index, as it’s called, shows that over the most recent ten years for which data are available, on average it’s not even slightly unusual for police at the municipal and county levels, and statewide, to stop black drivers disproportionately—at uncannily similar rates of disproportion. Put another way, all else equal, police in Missouri generally stop black drivers about 40-55% more frequently than the African American portion of the driving- age population would predict under random conditions. (That presupposes, thornily, that (a) traffic enforcement should be random; and (b) that the underlying driving and criminal behavior of motorists does not vary substantially across different racial groups or neighborhoods.) Nonetheless, by this popular-if-flawed scholarly standard, it seems Ferguson’s police department even compares well.

In fact, according to state-mandated reports, the Ferguson Police Department (FPD) “Disparity Index” for stops of black drivers has for the past eight years been about ten percent lower than the corresponding figure for the whole state…

…and is almost statistically indistinguishable, on average, from the St. Louis County police. By this measure of possible police bias, Ferguson looks relatively good.

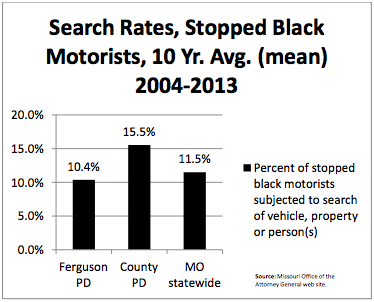

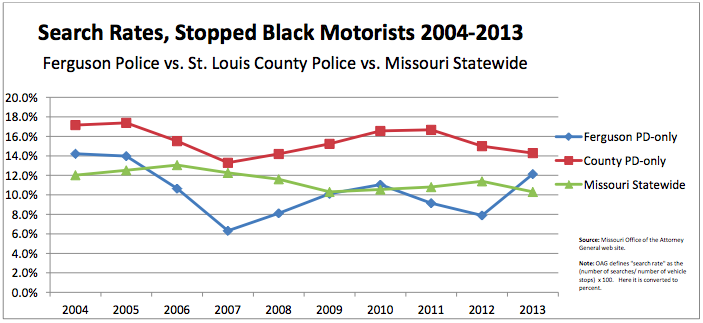

So maybe Ferguson police reveal anti-black bias by conducting searches of stopped black motorists more often than other police agencies do?

No. On average over the prior ten years, Ferguson officers conducted such searches at rates slightly lower than the statewide average—and fully a third lower than did St. Louis County police operating in the same region.

What’s more, over the same ten years, FPD’s search rate for stopped black motorists never once exceeded the County Police rate of searches:

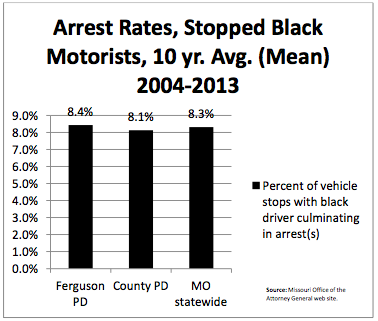

So perhaps FPD as an agency has exhibited bias by arresting a substantially greater portion of stopped black motorists than comparable law enforcement agencies?

Nope. Here, too, Ferguson PD’s performance is right on pace with County and statewide norms.

In fact, despite modest variation over the ten-year period, FPD’s arrest rates of black motorists were consistently within about three (often fewer) percentage points of both the County PD and statewide figures:

Notably, the year-to-year trend lines at all three jurisdictional levels roughly mimicked common up-turns and down- turns, suggesting that patterns of motorist behaviors were trending up or down, not levels of professional bias transcending police agencies.

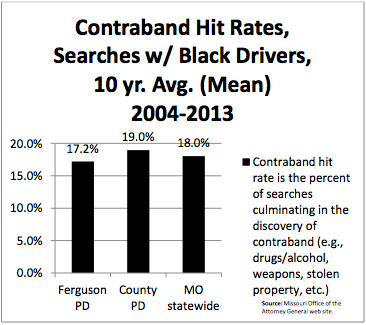

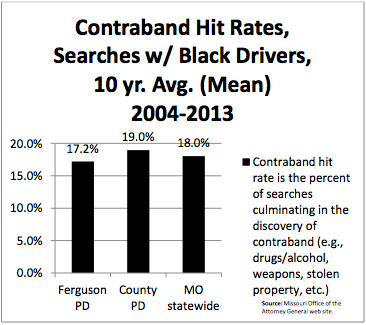

So perhaps the alleged bias inherent in ‘over-policing’ and ‘over-searching’ of African American motorists stands out markedly in Ferguson PD’s contraband hit rates, commonly described by critics as a measure of how ‘off-the-mark’ police hunches and pervasive stereotypes are?

No, only tiny differences in FPD’s ten-year average hit rate, compared to County Police or statewide numbers.

The only evident contrast was Ferguson’s hit rate trending modestly upward over the prior four years, suggesting perhaps that FPD searches were becoming either better-executed or better-targeted or both:

So how is it possible that the Ferguson Police Department’s rates of stopping, (un)successfully-searching and arresting black motorists—all highlighted in the Justice Department’s recent blistering critique—are said to illustrate an agency plagued by unusually widespread racial bias in contrast to other law enforcement agencies? Plainly, these metrics cannot show that, because they are not unusual. Published prior to the DOJ’s galloping 2015 assault on Ferguson PD’s reputation, a 2014 piece in the St. Louis Times-Dispatch also confirmed the Ferguson vehicle stop-related numbers don’t stand out by the standards of the region. It turns out FPD’s data on vehicle stops, searches and arrests fall well within the norms of Missouri policing.

So perhaps the norms of policing roadways and African American motorists across Missouri are themselves steeped in racial bias, in contrast to most police agencies outside the state?

That argument was summarily dispatched in a 2013 NPR story with this headline: “Missouri’s racial disparities in traffic stops mirror national trends” Excerpt: “Over the years, the study [of Missouri policing by scholars] consistently shows that African-American drivers are stopped more than other racial groups. University of South Carolina criminology professor Jeffrey Rojek has worked on the project for more than a decade. He says the finding is not unique to Missouri, but nationwide.”

So, if Ferguson’s Police Department is not an outlier in its patterns of policing black motorists, but rather a national emblem of widespread practices, what is the prevailing explanation for these national enforcement practices?

Left-wing explanation: Yes, most police officers and agencies in the U.S. routinely practice racially-biased law enforcement, especially but not exclusively white male officers against black male citizens. Bias, liberals say, is ubiquitous.

Right-wing explanation: Highly disparate rates of unlawful driving and criminal behavior by a subset of black Americans more than amply explain and justify the geographic, and therefore demographic, patterns of policing across America. Simply put, say the conservatives, cops go where reported and observable crime most often happens.

Can these explanations be meaningfully reconciled? Indeed, are these claims reciprocally-contingent?

Despite Eric Holder’s thin claims to the contrary, the Justice Department broadside on the tiny Ferguson PD for its reportedly systematic bias in policing of black motorists—at the very least—is ripe for generalization to many, many metropolitan American police agencies. In declaring his willingness (if not his agency’s authority) to dismantle the Ferguson Police Department “if necessary,” outgoing AG Eric Holder has not minced words. As recently reported in The Washington Post:

Holder said he believes what happened in Ferguson is an “anomaly,” but he hopes that law enforcement agencies around the country are paying attention to his comment and the report — that they “understand the intensity with which the feelings are felt at the federal government level to ensure that we use all the tools that we can to make sure that what happened in Ferguson is uncovered and simply does not happen in any other part of the country.”

True: Few are defending FPD, and no one is defending the anecdotal excesses and episodes of naked misconduct by some individual officers there. In itself, officials in the Civil Rights Division probably hope that is a lesson in its own right to other agencies.

True also, publicly mounting even a measured defense of the Ferguson Police Department in the current climate is likely an exercise in political futility, if not career suicide, for law enforcement leaders nationwide. Locally, unless they exhibit an unlikely blend of moral nuance, political stamina and intellectual courage, Ferguson officials can be expected to continue their hurried rush down DOJ’s prescribed path of reform. And don’t expect (m)any scholars, policing experts or mainstream commentators to show much more pluck, much less chutzpah, in this public monologue while it still masquerades as discourse. The politics of campuses, cities and journalism make that very, very unlikely.

Certainly, though, DOJ’s racial concerns extend far beyond Ferguson roadways and, indeed, far beyond Ferguson. And of course there is much more to be done in mapping the core of Ferguson’s challenges, restoring popular trust and charting solutions—which, appropriate or not, DOJ will seek to press fit onto many more jurisdictions, by hook or by crook. Administration voices will invoke all their institutional, rhetorical and even statistical power. But their bully pulpit has few levers, beyond spot grant funding. And—much like the Civil Rights Division’s woefully-belated vindication of Officer Darren Wilson—the public may radically reconceive the notion of bias in policing.

Finally, DOJ action could catalyze such new thinking in unintended ways. For instance, the headlong federal embrace of data analysis, “evidence-based methods” and the doctrine of “Disparate Impact” may yet backfire in grand fashion, if the weight of the data continues to fall toward awkward conclusions about epic racial differences in offending, more so than unlawful bias by police. If so, the legal theory of Disparate Impact as stand-alone evidence of institutional racism or biased policing could quickly collapse—right alongside the legacy of former Attorney General Eric Holder. That would be a calamity for progressives and African Americans alike. No doubt only time will tell, even when the current media din from Washington does not.