Diversity Macht Frei

September 7, 2016

I’ve finished reading The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise and can give it my highest recommendation. I’ll write about it some more in future blog posts. My favourite element of the book is where he quotes various Islamophilic “scholars” who have lauded Islam’s tolerance and the supposedly happy and peaceful coexistence in Muslim-controlled Spain and then makes these quotes look ridiculous through his own scholarship.

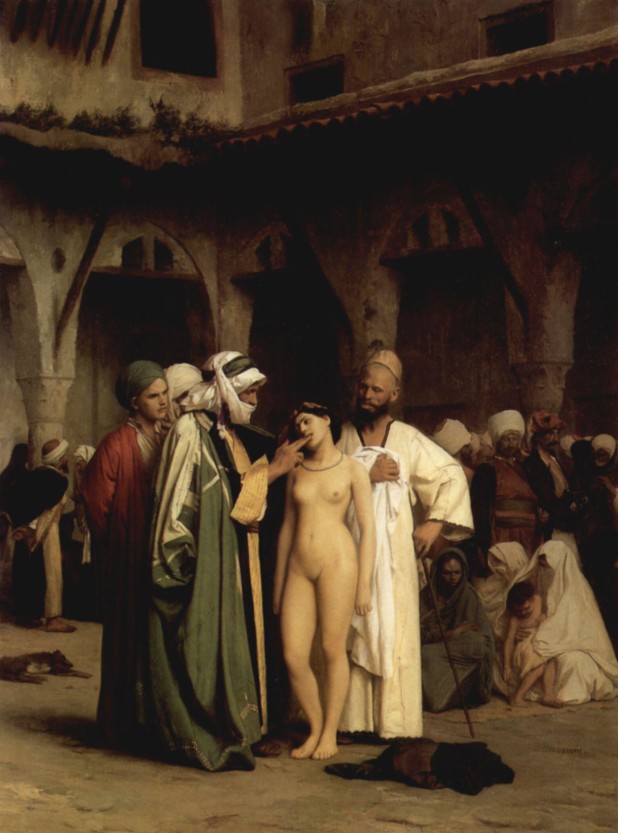

One example of this is the praise bestowed on the “liberated” women of Al-Andalus, some of whom left poetry or other written works. Muslims and feminists have claimed that this shows Islam was more enlightened and accepting of female empowerment than Christian civilisation was. Many of these writers seem to be unaware that the “liberated women” they are talking about were, in fact, captured Christians forced to serve as Muslim sex slaves. To please their masters more, and to enhance their resale value, they were forced to study poetry and various branches of learning. This is what feminists consider “female empowerment”. I’ll omit the standard quote facility because this is a long passage and italics weary the eye.

Universalism, longtime-defended by the prophets since Noah, Abraham, and Moses, reaffirmed by Christ in the name of the new covenant, and realized in Islam, in the Andalusian model of Spain, is a permanent virtue in a Palestinian model [that would supersede Israel] in which Jews, Christians, and Muslims can live again and under its protection [emphasis added]. —Hassan Hanafi, Chairman of the Department of Philosophy at Cairo University, cited as “a leading exponent in contemporary Islam of the reconciliation between faith and reason” in Arthur Herzberg, Jewish Polemics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), 224

In Maliki jurisprudence, a slave girl, either bought at the marketplace or captured in war, with whom her master had sex, became his sexual slave or jariya (or djariya, a “concubine”). Under the Umayyads, al-Andalus became a center for the trade and distribution of slaves: young female sexual slaves, sometimes as young as eleven years old; male children castrated to become eunuchs in the harems; male children brought up in barracks to be slave warriors; male children used as the sexual playthings of the powerful and wealthy (as in the case of Abd al-Rahman III’s “love” for the Christian boy Pelayo); men used as servants or workers—for every conceivable use human beings of all ages and races were bought and sold.

The price of a slave depended on his or her race, sex, age, and abilities. White slaves, especially blond ones, often captured in raids of Christian lands, were the most prized. In the year 912, during the Islamic Golden Age of the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba, the price for a male black slave was 200 dirhems [coins] of silver. A black girl from Nubia went for 300 dinars of gold. A white girl without education cost 1,000 dinars of gold. A white girl with singing abilities cost 14,000 dinars. In Abd al-Rahman III’s court there were 3,750 slaves, his harem had 6,300 women, and his army included 13,750 slave warriors. A document from the twelfth century tells of the tricks used by sellers of slaves in the Muslim slave markets: merchants would put ointments on slave girls of a darker complexion to whiten their faces; brunettes were placed for four hours in a solution to make them blond (“golden”); ointments were placed on the face and body of black slaves to make them “prettier.”

“The merchant tells the slave girls to act in a coquettish manner with the old men and with the timid men among the potential buyers to make them crazy with desire. The merchant paints red the tips of the fingers of a white slave; he paints in gold those of a black slave; and he dresses them all in transparent clothes, the white female slaves in pink and the black ones in yellow and red.”

A thirteenth-century epistle by the faqih Abu Bakr al-Bardai shows how a respectable Muslim man in al-Andalus would regard a sexual slave girl as a source of “love. The poetry of the twelfth-century writer al-Saraqusti Ibn al-Astarkuwi is a good example of this “delightful Andalusian love poetry” that so many Western scholars have praised, oblivious to its sordid cultural context: that it is about sexual slave girls, not about the secluded hurras or muhsanas [Muslim women] of al-Andalus, who went about covered from head to toe.

In the Islamic world, harems (not a Christian institution, for contrary to what is sometimes written, there were no harems in the Christian Greek Roman Empire) swarmed with female captives from foreign lands: white women from Persia, Kurdistan, the Christian Greek Roman Empire, Christian Spain and Armenia; darker ones from Ethiopia, Sudan, and India. Harun al-Rashid had a thousand sexual slaves; Al-Mutawakkil had four thousand; Abd al-Rahman III had more than six thousand; al-Mutamid of Seville, overthrown by the Almoravids, left behind a harem of eight hundred women, counting wives, sexual slaves, and female domestic servants. The Moroccan writer Fatima Mernissi recounts: The harems became places of the greatest luxury where the most beautiful women of the world played their cultural differences and mastery of diverse skills and knowledge like winning cards for seducing caliphs and viziers.

In order to seduce these men, it was not enough just to bat one’s eyelashes. One had to dazzle them in the fields that fascinated them, astrology, mathematics, fiqh, and history. On top of these came poetry and song. Pretty girls who got lost in serious conversations had no chance to be noticed, and even less chance to last; and the favorites, who knew this very well, surrounded themselves with competent teachers.

Ibn Hazm commented on these women’s total dedication to sexual conquest as the underlying reason for their various skills: “As for the reason why this instinct [this preoccupation with sexual matters] is so deeply rooted in women, I see no other explanation than that they have nothing else to fill their minds, except loving union and what brings it about, flirting and how it is done, intimacy and the various ways of achieving it. This is their sole occupation, and they were created for nothing else.”

If these sexually skilled girls succeeded in becoming favorites of their masters, they could themselves have women servants. Some ingenious academic specialists have argued that by permitting slave girls to learn skills that increased their sexual attractiveness in the eyes of their masters and granting them relatively greater freedom in the public sphere, sexual slavery under Islam actually promoted women’s liberation. An article published in the New York Times has likened the sexual slaves’ conniving for power in the harem to the struggles of Western women in the corporate world.

Other efforts to downplay the phenomenon of massive slavery in the Islamic empires have been similar marvels of academic ingenuity. Thus, defending slavery in the Islamic Mamluk empire, a medieval studies scholar offers the official view among specialists: It is important to understand that medieval Islamic civilization had a different attitude towards slavery than that seen in western Europe. Slaves were much better treated and their status was quite honourable. Furthermore, the career opportunities [!] open to a skillful mamluk, and the higher standards of living available in the Islamic Middle East, meant that there was often little resistance to being taken as a mamluk among the peoples of Central Asia and south-eastern Europe. Many young Kipchaq Turkish women, slaves and free, also arrived in the wake of mamluk recruits, bringing with them some of Central Asia’s traditions of sexual equality.

One can certainly imagine the throngs of girls and boys in Greece, Serbia, and Central Asia clamoring to be taken away from their families to be circumcised, to become sexual slaves, or to be castrated to guard harems as eunuchs, or, in other cases, to be raised in barracks with the sole purpose of becoming fearless slave-soldiers. Or one can imagine among Egyptian youth the same interest in a “career” as a slave, which would have made it unnecessary for Mamluk rulers in Egypt to raid foreign lands to obtain replacement slaves or to buy them at the slave markets.

But aside from the basic human problem involved in all this, the professor overlooks that in fact, as Bernard Lewis and Daniel Pipes have pointed out, in Islam there existed two fundamental categories of people: slaves and nonslaves. That is why enslaving Muslims was soon discouraged in early Islam and eventually prohibited. Against this distinction (being enslaved or selling oneself into slavery was not honorable, and that is why it did not accord with being a Muslim), the rest are mere academic discussions about how the various Islamic empires (or the various Western empires and cultures) handled this “peculiar institution”: “more humanely” or “less humanely”; “with more sophistication” or “with less sophistication”; “with greater possibility of well being” or “with less possibility of well-being”; “with the possibility of having children who would become rulers”; “being a slave soldier, which had greater prestige,” etc. There was nothing “better” about slavery under medieval Islam: it was a system based on the looting of humans and their degradation in the slave markets.

Source: The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise – Muslims, Christians, and Jews under Islamic Rule in Medieval Spain by Darío Fernández-Morera

Here, in an article titled “How did Islam contribute to change the legal status of women?” another writer argues that Christian women being held as sex slaves by Muslims enhanced Islam’s “tolerance”.

Those who benefited from this power were only the relatives of the jawa ri [female slaves] or those whom they held in favor, but rather the entire ethnic or religious group to which the ja riya belonged. Khlid al-Qasri , the governor of Iraq had erected a church in K fa for the Christian community under the influence of his mother, who was a Christian herself. Khalid was generous in his nomination of Christian functionaries to officials positions for the sake of his mother. The phenomenon of tolerance toward the non-Muslim communities was probably affected by the religious tolerance within the palace of the caliphate itself. In the courtyard of the palace of al-Ma’m n, Christmas would be celebrated by the Christian jawa ri of the palace, with all the hallmarks of the religious ceremony, as the caliph himself looked on and joined in the merriment of the rejoicing jawa ri .

And slave owners forcing their female slaves to acquire various “accomplishments” in order to increase their value “contributed to the prevalence of education among women”.

The slave traders believed it was worth while to train and educate female slaves so that the latter would attain better profit for them, since an educated slave woman was worth more than an uneducated woman. The market made a clear distinction between an educated slave woman and an uneducated one, who was known as s dhaj. The demand for educated a slave women was greater, particularly among clients from the ruling elite, who would take pains to find out how educated a slave woman was before purchasing her. 116 The basic subjects of erudition can be divided into three main areas: the Arabic language, the Qur’ n, and the study of poetry by rote. It should be pointed out that the study of poetry was crucial to those who wished to specialize in singing, and almost all qiy n demonstrated admirable expertise in this field. 118 But there were apparently also jaw r who specialized in specific fields such as the Qur’ n and qir ’ t (ways of reading the Qurn), or ad th and theology (fiqh). There were also those who were proficient at literary writing and written expression. Worthy of mention in this respect was the legendary female slave of al-Rash d, the caliph, whose name was Tawaddud and who was the hero of one of the Thousand and One Nights stories. This slave woman was purported to have outshone all of the outstanding scholars of the royal court in all areas of study and in fields connected to such academic areas as literature and the exact sciences. Ignoring the legendary element of the story, which is the same as in any such tale, the story of this slave woman reflects the thinking of the age and the common perception of the slave women in Muslim society.

The education of jaw r , which was intended primarily as a means of increasing the slave traders’ profits, contributed to the prevalence of education among women, a characteristic which in the Muslim world had formerly been monopolized by men. Toward the beginning of the fourth/tenth century, there were women who demanded the right to occupy positions which had heretofore been reserved for men.

Perhaps a thousand years from now the Muslim grooming gangs who have enslaved and gang-raped thousands of British children will be praised as bold pioneers of intercultural understanding.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History