Hunter Wallace

Occidental Dissent

March 24, 2017

A new study has found that something went terribly wrong for the White working class in the job market of the 1970s which is reducing their life expectancy:

“WASHINGTON (AP) — Middle-age white Americans with limited education are increasingly dying younger, on average, than other middle-age U.S. adults, a trend driven by their dwindling economic opportunities, research by two Princeton University economists has found.

The economists, Anne Case and Angus Deaton, argue in a paper released Thursday that the loss of steady middle-income jobs for those with high school degrees or less has triggered broad problems for this group. They are more likely than their college-educated counterparts, for example, to be unemployed, unmarried or afflicted with poor health.

“This is a story of the collapse of the white working class,” Deaton said in an interview. “The labor market has very much turned against them.” …

Since 1999, white men and women ages 45 through 54 have endured a sharp increase in “deaths of despair,” Case and Deaton found in their earlier work. These include suicides, drug overdoses, and alcohol-related deaths such as liver failure.

In the paper released Thursday, Case and Deaton draw a clearer relationship between rising death rates and changes in the job market since the 1970s. They find that men without college degrees are less likely to receive rising incomes over time, a trend “consistent with men moving to lower and lower skilled jobs.”

Alana Semuels has more on this in The Atlantic:

“Now, in a new paper, the economists explore why this demographic is so unhealthy. They conclude it has something to do with a lifetime of eroding economic opportunities. This may seem like a circular argument, when put together with previous work: Middle-aged Americans aren’t working because they’re sick, and middle-aged Americans are sick because they’re not working. But Case and Deaton argue that it’s not just poor job opportunities that are affecting this demographic, but rather, that these economic misfortunes build up and bleed into other segments of people’s lives, like marriage and mental health. This drives them to alcoholism, drug abuse, and even suicide, they say, in a new paper released Thursday in advance of a conference, the Brookings Panel on Economic Activity.

“As the labor market turns against them, and the kinds of jobs they find get worse and worse for people without a college degree, that affects them in other ways too,” Deaton told me.

What differentiates Case and Deaton’s paper is this idea that as people get older and their fates deviate more and more from those of their parents, they struggle to keep their lives together. The very act of doing worse than their parents’ generation—what Case and Deaton call “cumulative disadvantage”—is killing them. …”

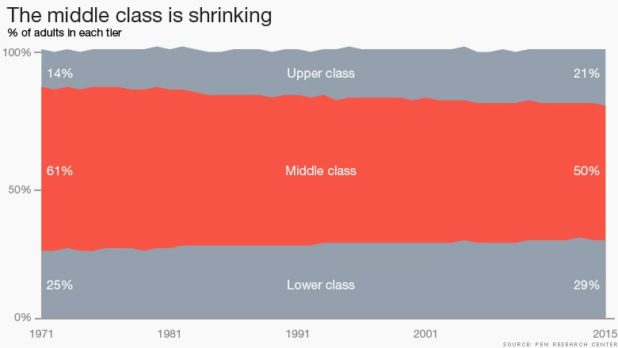

The American middle class has been shrinking since the 1970s:

What could possibly explain this? In December 2015, I speculated it was related to the triumph of free-trade in the United States after the Kennedy Round of GATT:

The Pew Research Center has a massive new study out which shows the US middle class is losing ground:

“After more than four decades of serving as the nation’s economic majority, the American middle class is now matched in number by those in the economic tiers above and below it. In early 2015, 120.8 million adults were in middle-income households, compared with 121.3 million in lower- and upper-income households combined, a demographic shift that could signal a tipping point, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of government data …

Fully 49% of U.S. aggregate income went to upper-income households in 2014, up from 29% in 1970. The share accruing to middle-income households was 43% in 2014, down substantially from 62% in 1970.

And middle-income Americans have fallen further behind financially in the new century. In 2014, the median income of these households was 4% less than in 2000. Moreover, because of the housing market crisis and the Great Recession of 2007-09, their median wealth (assets minus debts) fell by 28% from 2001 to 2013.”

The Pew study doesn’t hazard to guess why the American middle class has shrunk in relative size in every consecutive decade since 1971. I believe, however, that I have found the answer in Pat Buchanan’s book The Great Betrayal:

“When and how did the free-traders capture America?

If one year could mark their decisive victory, it would be 1934, with the passage of the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act. And if one year could be cited as the inauguration of the free-trade era, it would be 1967, with completion of the Kennedy Round of trade negotiations.”

The Kennedy Round of GATT was the fateful moment when America leapt off the cliff and went full retard on free-trade:

“In 1967 America arrived at the final crossroad. The Kennedy Round of trade negotiations under GATT was stalled. Europeans were balking at U.S. demands to further open their markets to American agriculture; Japan had given a flat no to greater market access. Fear gripped Washington. The talks were on the verge of collapse.

The U.S. trade negotiators went to see President Lyndon Johnson. Failure to end the Kennedy Round successfully, they warned, would return global trade to “jungle warfare,” risk “spiraling protectionism” in the United States, and “encourages strong forces now at work to male the [European Common Market] into an isolationist, anti-U.S. bloc, while, at the same time, further alienating the poor countries.” If America did not make the necessary concessions, disaster was certain.

Again the United States capitulated; and Commerce Secretary Alexander Trowbridge rejoiced.”

Buchanan continues:

“LBJ crushed the uprising with a flat declaration. No quota bill will “become law as long as I am president and can help it.” By the end of the sixties, early returns from the Kennedy Round were coming in. America had entered a new era”

He quotes trade historian Alfred E. Eckes, Jr.:

“Viewed from a historical perspective, the Kennedy Round marked a watershed. In each of the seventy-four years from 1893 to 1967 the United States ran a merchandise trade surplus (exports of good exceeded imports). During the 1968-72 implementation period for Kennedy Round concessions, the U.S. trade surplus vanished and a sizeable deficit emerged. For twenty of the next twenty-two years, the United States experienced merchandise trade deficits – as much as $160 billion in 1987.”

Buchanan explains what happened next after the Kennedy Round was implemented from 1968 to 1972:

“The Kennedy Round tore down the levees, and floods of imports poured in from low-wage nations. With the tariff collapsed, American companies had a powerful incentive to relocate factories abroad, to take advantage of the low-wage labor and then export back to the United States. Journalists were soon writing excitedly about the Japanese “miracle” and the “tigers” of Asia – Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea. Few asked at whose expense this sudden Asian prosperity had come.

One after another of the great U.S. industries began to decline, depart, or die. The radio- and television-manufacturing industries disappeared. The antifriction-bearings industry and machine-tool industry were gutted. The mighty auto industry was ravaged. Five years after the Kennedy Round, foreign penetration of the U.S. auto market had doubled, to 16 percent. But in Europe and Japan, internal tariffs, targeted at American-made cars, kept U.S. exports from making comparable gains.”

Back to trade historian Alfred E. Eckes, Jr.:

“In the twenty years after 1970 the opportunities Kennedy foresaw vanished for high-paid but relatively low-skilled U.S. workers. From 1972 to 1992 the United States created 44 million net jobs – particularly in services and government. However, America generated no net jobs in internationally traded industries. Japan and many of the other rapidly industrializing powers – Taiwan, South Korea, and Brazil among others – enjoyed rapid economic growth, not because they practiced free trade at home, but because they enjoyed access to the open American market. Like nineteenth-century America, they practiced protectionism at home while America’s generous market-opening policies provided boutiful export opportunities. Paul Bairoch noted the lesson: “Those who don’t obey the rules win.”

With the sole exceptions of 1973 and 1975, the US has ran a trade deficit with foreign countries since 1971, 42 out of the last 44 years of the free-trade era. Isn’t that an amazing coincidence?

Of course there were many other things going on in the US in 1971 that also contributed to this turning point for the White working class: the most important being the great tidal wave of Third World immigration that followed the Immigration Act of 1965, the mass entry of women into the labor market, the end of the Bretton Woods system after Nixon floated the dollar, the decimation of organized labor in the 1970s and 1980s, the triumph of deregulation across multiple industries and Ronald Reagan’s changes to the tax code. All of these things have contributed to a great winnowing of the American middle class and the creation of a more Latin American-style economy.

OxyContin entered this dismal picture in the mid-1990s:

“The state of Kentucky may finally get its deliverance. After more than seven years of battling the evasive legal tactics of Purdue Pharma, 2015 may be the year that Kentucky and its attorney general, Jack Conway, are able to move forward with a civil lawsuit alleging that the drugmaker misled doctors and patients about their blockbuster pain pill OxyContin, leading to a vicious addiction epidemic across large swaths of the state.

A pernicious distinction of the first decade of the 21st century was the rise in painkiller abuse, which ultimately led to a catastrophic increase in addicts, fatal overdoses, and blighted communities. But the story of the painkiller epidemic can really be reduced to the story of one powerful, highly addictive drug and its small but ruthlessly enterprising manufacturer.

On December 12, 1995, the Food and Drug Administration approved the opioid analgesic OxyContin. It hit the market in 1996. In its first year, OxyContin accounted for $45 million in sales for its manufacturer, Stamford, Connecticut-based pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma. By 2000 that number would balloon to $1.1 billion, an increase of well over 2,000 percent in a span of just four years. Ten years later, the profits would inflate still further, to $3.1 billion. By then the potent opioid accounted for about 30 percent of the painkiller market. What’s more, Purdue Pharma’s patent for the original OxyContin formula didn’t expire until 2013. This meant that a single private, family-owned pharmaceutical company with non-descript headquarters in the Northeast controlled nearly a third of the entire United States market for pain pills. …

No state has been more devastated by the nationwide opiate problem than Kentucky. Much of the eastern part of the state and the Appalachians has watched as men, women, and teenagers fell victim to the potent pain pills. There were several different gateways — back injuries, operations, parents’ medicine cabinets — but all of them led to an implacable addiction that rivals that of the hardest street drugs. And that’s the rub. Because there was simply so much OxyContin available for over a decade, it trickled down from pharmacies and hospitals and became a street drug, coveted by teens and fiends and sold by dealers at a premium (prices often shot up well over $1 a milligram, pricing the popular 80mg tablets at over $100 for a single pill). …”

Allow me to set the scene.

Imagine a small town in Trump’s America. Since the 1960s, it is has probably gained a new Wal-Mart and commercial strip while it has lost many businesses in its downtown commercial district which have been replaced by bars. Multiple factories have likely shut down and moved overseas. Third World immigrants have arrived from Latin America and Asia and have established enclaves.

In the wake of feminism, women entered the workforce and the family has broken down. It is not uncommon these days to see White men struggling with their second or third marriage. Overall, the local culture has become less religious and drugs like heroin and painkillers like OxyContin have become a problem. Everyone has an iPhone or Android manufactured in East Asia though. Wall Street is doing great but the rise of the stock market seems to be a contrary indicator in your community.

Liberty has triumphed across the board in sex, gender identity and family life. Liberty has triumphed in immigration. It has triumphed in trade policy and regulation. It has even triumphed in attitudes toward drug abuse which is strange given the declining life expectancy of White Americans. The abuse of OxyContin is a win-win because both parties benefit in a free-market transaction!

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History