The Nation

March 26, 2014

Thirty years ago, on June 17, 1984, Jean-Marie Le Pen burst into the limelight when his party, the radical-right National Front, scored a record 11 percent in the European Parliament election on an anti-immigration, anti-Europe nationalist platform. France was stunned. On election night, the 55-year-old Le Pen, smug and sententious in a dark-blue blazer, predicted, “This is only a beginning,” calling the victory “the first stage in a long journey that will lead to France’s rebirth.” But even in his wildest dreams, Le Pen could not possibly have pictured his own daughter Marine, now the head of the National Front, riding the crest of one of the worst social, economic and cultural crises in France to lead the polls ahead of every other contender. A January 25 survey credited the National Front with 23 percent of the vote in the May European Parliament elections, ahead of the Socialist Party and the right-wing Union for a Popular Movement (UMP). If the prediction comes true, hers would become the leading political force in France.

How did a fringe party born in 1972 of an eclectic coalition of former collaborationists, neofascists, anti-Zionists and opponents of decolonization become, if not mainstream, at least increasingly attractive? Did the National Front tone down to adapt to France’s political ecology, or did France veer dangerously to the right? And how much higher can the National Front rise? With nationwide municipal elections coming in March and the European Parliament elections two months later, 2014 will be a crucial year for the National Front—and for France, which is summoned to resist, or heed, the siren song of far-right populism.

Marine Le Pen is often described as the driving force behind this staggering ascent. There is no doubt that the perky 45-year-old blonde has managed to put a modern gloss on an old political brand. When she took over the party in 2011, Le Pen’s last name was a liability as much as an asset: voting National Front was taboo, and few were open about doing it. Now “Marine,” as everyone calls her, is a rising star. Journalists rush to be the first to report her latest zinger. Bystanders jostle to get their picture taken with her in the open markets. She cracks a joke, kisses the grandmas on the cheek or bursts into her extensive repertoire of French pop songs from the 1970s. Forthright and good-humored, the down-to-earth mother of three comes across as a brave, outspoken mom ready to take hits in the wild west of politics. “She has glorious balls,” volunteered Gilbert Collard, formerly a left-wing immigrant rights advocate who succumbed to Marine’s charm and is now a congressman affiliated with the National Front.

Like Collard, many voters who fall for Marine would never have voted for Jean-Marie. The comparison with her father serves her well (it’s easy to look angelic next to the “devil,” as he has been called); so does the generational gap between the two. That a woman born in 1968 is at the head of the formerly macho, rearview-mirror-looking far-right party is in itself a revolution of sorts. A twice-divorced single working mother, Marine “looks” feminist without having much to show for it. Having inherited a party that called abortion “anti-French genocide” and compared it to the crematoria at Auschwitz, she has only to be mildly moderate on the issue—proposing to stop reimbursing pregnancy terminations—to sound liberal.

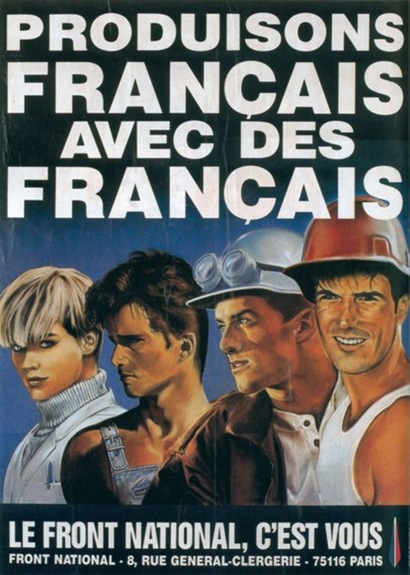

Her appeal also comes from a well-orchestrated media strategy. Even before she took over the party in 2011, Marine had pushed for a sweeping makeover of the Le Pen brand to make it more palatable to new segments of the electorate: out with the anti-Semitic gibes her father used to slip in to draw media attention; in with a carefully polished image, a strategic use of republican values to castigate Islam in the name of secularism, and a revamped economic agenda that quotes Nobel Prize–winning economists Joseph Stiglitz and Paul Krugman to lend credibility to her bid for power. She has reined in and professionalized the party, enforcing a zero-tolerance policy for members’ display of Nazi paraphernalia and racist comments made in public, and recruited a new cadre of neat and tidy twenty- and thirtysomethings with clean hands and unambiguous pasts. She is out to win the youth vote, trusting that references to the Algerian war or World War II (a damning point for the National Front, known for its colonial nostalgia and revisionist sympathies) are mostly lost on new generations. Instead, she offers quick party promotions to young activists: in the March municipal elections, 14 percent of her candidates will be 30 or younger. The National Front’s only MP, Marion Maréchal- Le Pen (Marine’s niece), was elected at 22.

The new faces come with new words. Like other European far-right movements, such as Geert Wilders’s Party for Freedom (PVV) in the Netherlands, the National Front has launched a semantic takeover of democratic, even leftist, keywords. Inspired by Gramsci’s theory of ideological hegemony, the National Front understood the power of words as early as the 1990s. Internal notes leaked to the press at the time revealed a concerted plan to win the semantic battle and impose their vocabulary—and worldview—on the public debate: immigrant rights associations such as SOS Racism were to be called “the pro-immigration lobby”; mondialisation(globalization) was renamed mondialisme to insinuate through rhyme more than reason an ideology as dangerous as communism. Above all, the term extrême droite (far right) was banned in favor of the more presentable vraie droite (real right). (In line with this legacy, Marine Le Pen has recently threatened to sue journalists who would label her party as belonging to the far right—a strange move for a self-proclaimed champion of a free press.)

Now the National Front is going one step further, hijacking and exploiting the very concepts it used to oppose. Le Pen invokes “liberty,” “democracy,” “justice” and “secularism” to back her claims that “the system” is betraying France’s republican principles. Never mind that the National Front is the political heir of anti-republican, anti-Enlightenment, even royalist radical-right movements such as Action Française (the National Front’s candidate for the fourth arrondissement of Paris is a member of the royalist league). The “new” National Front is eager to show respect for the letter, if not the spirit, of democratic principles.