Daily Mail

November 28, 2013

We, the English-speaking peoples, invented freedom. We gave the world the glorious concept that the law was something bigger than the wishes of the king or the strongest man in the tribe. We taught other nations that the state could be the servant of the citizen, rather than the other way around.

So why do we now shy away from the uniqueness of our achievement? It’s extraordinary that we don’t want to pass on to our children the fact that they are heirs to a sublime tradition.

Personal liberty, the rule of law, representative government: these things are not, as we sometimes like to think, the natural condition of an advanced society.

Jury trials, parliamentary elections, habeas corpus, secure property, legal equality for women: the temptation is to think that all countries will adopt these things when they become rich enough and educated enough.

In fact, these concepts were largely developed in the English language. We call them ‘Western’ to be polite and modest. What we really mean is that they were the values of the Anglo-American system of government.

They became ‘Western’ because of a series of military victories by the English-speaking peoples – what we might call the Anglosphere.

But there comes a point when modesty tips over into self-loathing. Then, we focus obsessively on the bad things we’re supposed to have done, notably our exploitation of colonies, without seeing the bigger picture: how we brought those colonies to independence, in most cases, without a shot being fired in anger; our relentless and selfless campaign against the slave trade; our war against the Nazi tyranny.

Who has done more to spread freedom across the continents? You’d think that Leftists would be proud of this heritage.

In what other civilisation were civil rights so strong? In Africa? Tsarist Russia? Maoist Chin

Like every country, we have had our shameful moments, of course. But when the balance is weighed, few places have contributed so much to the happiness of mankind. The story of freedom is a long one.

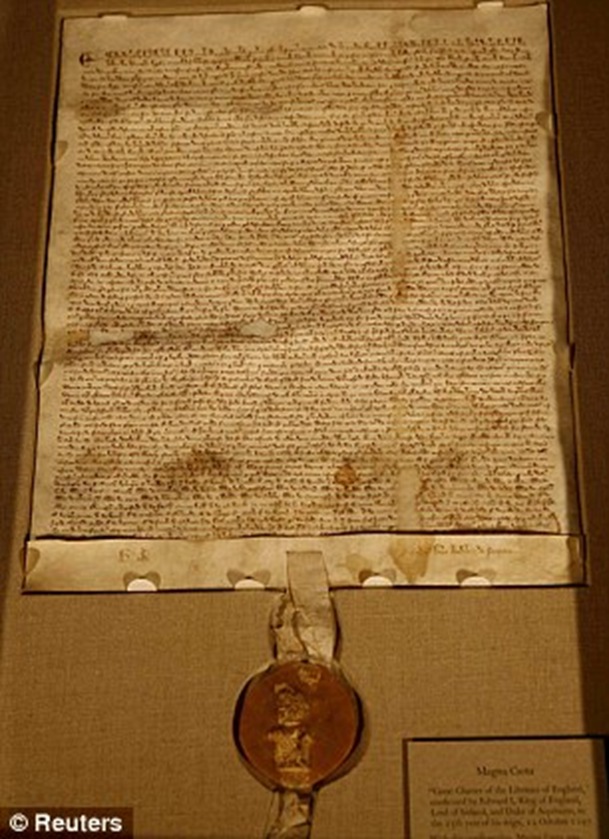

It stretches back through the Glorious Revolution of 1688 (when an authoritarian king was toppled in favour of parliamentary democracy) to the Magna Carta (the landmark 1215 document limiting his royal powers).

Right from the days of Anglo-Saxon England, we find peculiar legal and political structures that set this country apart.

For example, inheritance rules favoured the individual over the extended family. Kings were answerable to representative councils, Witans, which on occasion dictated terms to the sovereign. There was no separate aristocratic caste.

Above all, our remote ancestors came up with a legal system whereby the law grew like a coral, case by case, rather than being handed down by the government.

It is a bottom-up rather than top-down system and is therefore the property of the people not the state. Again and again, it has proved a sure defence against tyranny.

The happy accident of Great Britain being an island meant there was no need for a permanent standing army. Taxes were commensurately low, and the government commensurately weak. If the regime needed resources, it had to collect them by consent through the people’s representatives.

It is no coincidence that all the world’s oldest parliaments are on islands: England, Iceland, the Isle of Man, the Faroes. Because the state was weak, the individual was conversely strong.

In terms of the economy, for the first time since farming became widespread 6,000 years ago, it became more rewarding to make or sell things than to seize them from others. Production, as sociologists put it, became more attractive than predatory behaviour.

Social mobility rewarded effort. Prosperity followed. After hundreds of thousands of years of economic flat-lining, the human species took off.

English-speakers carried their unique political culture with them over the seas. The United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand formed a common and unique civilisation.

But the ideas could be spread without direct settlement: anyone could buy into them. This is why Bermuda is not Haiti, why Hong Kong is not China, why Singapore is not Indonesia.

Elsewhere, democracy took a different turn, elevating majority rule over individual liberty.

Not surprisingly, our values have come under constant attack.

In the 1930s the democratic-capitalist order was rejected by fascists and communists, who saw it as past its prime. ‘Capitalism has run its course,’ Hitler proclaimed.

Authoritarians of the Left and Right saw individualism as a perversion of the natural order. They believed statist ideologies, which elevated martial vigour, collective endeavour and self-sacrifice, were bound to triumph.

Yet what the Nazis called ‘decadent Anglo-Saxon liberalism’ was not in decline at all. It triumphed in 1945. Two generations later it also saw off the Marxist monolith of the Soviet Union, to emerge as the most successful system on earth.

The tragedy of our present age is that it is now under siege at home.

Having developed the most successful system of government known to the human race, the English-speaking peoples are turning on their own creation.

One vivid illustration of the problem is our approach to Europe.

Ever since I was elected to the European Parliament in 1999, a question has nagged away at me: how many of the EU’s 28 member states have my unshakable commitment to freedom under the law?

The truth is that the rule of law is regularly set aside when it stands in the way of what Brussels’ elites want.

For example, the euro-zone bailouts of countries such as Greece were in blatant defiance of Article 125 of the EU Treaty (which makes it illegal for one member to assume the debts of another).

Yet, as soon as it became clear that the euro wouldn’t survive without cash transfusions, the law was set aside.

To British eyes, the whole process seemed bizarre. Rules had been drawn up but, the moment they became inconvenient, they were ignored. In Brussels, though, objections seemed pernickety, legalistic and altogether very British.

EU laws are initiated by unelected officials. Taxes are levied without popular consent. Power shifts inexorably from elected representatives to standing bureaucracies.

As for the idea that the individual should be as free as possible from state coercion, this is regarded in Brussels as the ultimate Anglophone fetish.