Samuel G. Freedman

Tablet Magazine

August 9, 2013

One sun-baked day in October 1967, Jerry Izenberg drove up a cracked dirt road outside the hamlet of Slaughter, La., headed for the unpainted shack at its end. As he neared the structure, its front door swung open and a couple of chickens ambled out, followed by the prematurely aging black woman who lived there.

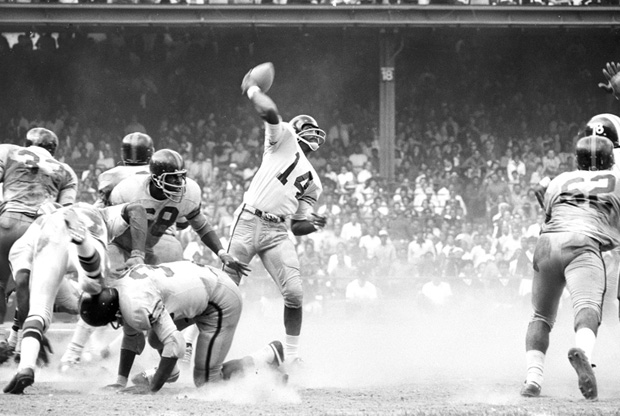

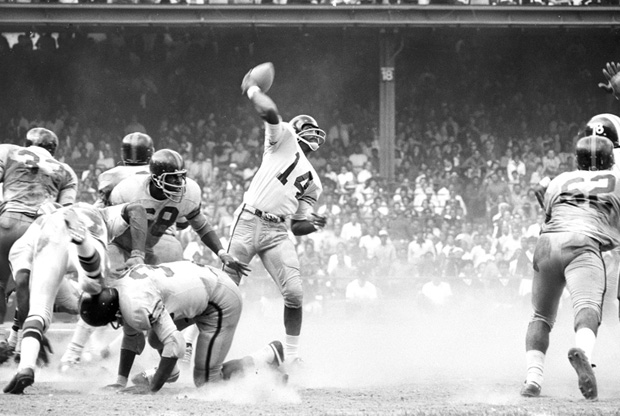

She was the mother of Henry Davis, the star guard on the football team at Grambling, a small black college in northern Louisiana. With a skeletal crew and a scant budget, Izenberg had come from New York to interview her as part of a film he was shooting for a New York television station.

Izenberg was treading ground that was uncommon enough for broadcast journalism at the time, reserved for the occasional socially conscious documentary like Harvest of Shame, which Edward R. Murrow had made several years earlier about migrant workers. Rarer still, unprecedented in fact, Izenberg was delving into the subjects of race, inequality, and civil rights in the course of making a film about sports.

Then again, Izenberg was himself a rarity: a sports-addled son of Newark, N.J., who had been instructed by Rabbi Joachim Prinz, a German Jewish refugee who was a confidante to Martin Luther King. And while Izenberg was chiefly a print journalist, he arrived at the Davis home with the backing of Howard Cosell, the country’s most famous sports broadcaster and an outspoken supporter of black athletes.

The resulting documentary, Grambling: 100 Yards to Glory, debuted in early 1968 on New York’s WABC with Izenberg as writer and producer. The film was shown with such reluctance by WABC’s leadership that it was consigned to an hourlong position at 10:30 on Saturday night. It might never have been seen at all without Cosell’s imprimatur as benefactor and executive producer.

Yet a chorus of praise had been building even before the broadcast, with columnist William N. Wallace in the New York Times declaring, “Do not miss it.” In the documentary’s immediate aftermath, influential sportswriters such as Shirley Povich in The Washington Post and syndicated columnist Red Smith added their endorsements. Six months after its obscure premiere, Grambling: 100 Yards to Glory received a national broadcast on the ABC network in a prime-time slot preceding the annual game between a college all-star team and the defending NFL champs. An Emmy nomination arrived several weeks later.

With the benefit of 45 years of hindsight, the impact of Grambling: 100 Yards to Glory is even clearer. It provided white America with one of its first glimpses of the parallel universe of black colleges, where football was only part of a culture of upward mobility and self-help. It told the story of Coach Eddie Robinson, who was developing dozens of players for eventual stardom in the NFL while preparing hundreds more for college degrees—and an escape from Jim Crow’s deprivations. And the film astutely wove together sports and societal issues in a manner that anticipated and in some ways inspired today’s sports documentaries, from Hoop Dreams and The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg to ESPN’s “30 By 30” series and HBO’s “24/7” series.

“Of all the things I’ve ever done, I feel proudest of this,” says Izenberg, 82 and still writing actively from his retirement home outside Las Vegas. “I didn’t feel like I was on a mission from God like the Blues Brothers. But maybe some higher power wanted me to show I could do something.”

***

To the degree that Izenberg’s own story starts in any particular place and time, it starts on a late afternoon in in Newark in 1943. On that day, 12-year-old Jerry had characteristically blown off his bar mitzvah lessons to play baseball. The rabbi found him on the diamond and pulled him home by the ear, threatening not to perform the bar mitzvah ceremony. As it happened, Izenberg’s father Harry knew of another rabbi in town: Joachim Prinz, who had been expelled from Nazi Germany just six years earlier.

They made an odd pair. Harry Izenberg worked in a factory dying furs, and Prinz was a yekke with a doctorate in philosophy. But Prinz had heard that Harry Izenberg had played semi-pro baseball, and he needed someone to teach him about baseball—not because he was interested, but because he wanted to be able to share his Americanized sons’ passion for the game. So, when the rabbi learned of Jerry’s dilemma, he promised to take over the bar mitzvah preparation.

Up until that point in his life, Jerry had absorbed a street Jew’s sense of identity. As a 7-year-old, he’d noticed an anti-Semitic slur chalked on the sidewalk. It served as a prop for Harry’s teachable moment: “Don’t look for trouble, but if anyone ever says that to you, smack ‘em in the mouth before they can say anything else.” An uncle once drove young Jerry to a hotel in a town called Mt. Freedom that posted a sign saying, “No Jews or Dogs Allowed.” Harry instructed Jerry never to forget it. When Joe Louis fought Max Schmeling, Harry made sure Jerry listened, and prize-fighting became a metaphor for defeating racial supremacy.

To these visceral forms of Jewish pride, Rabbi Prinz added theology and purpose. He taught Jerry a Judaism in which particularism and universalism entwined together to form a greater moral whole. “He burned in my brain that we are Jews and we’ve got to honor that,” Izenberg recalls. “But we’ve got to honor others, too.”

Izenberg’s idealism took another turn during his college years when he joined a Communist youth group—in itself a Jewish sort of thing to do in the immediate postwar years, especially because the American Communist Party championed civil rights. But after that flirtation ended, the influence of Rabbi Prinz remained: With the special credibility of a survivor of Nazi Germany, he had emerged as a national leader on civil rights. He spoke at the March on Washington. He participated in the Freedom Rides.

By that point, in the early 1960s, Izenberg had begun to fuse his love of sports with his commitment to racial equality. They came together in his nascent journalism career.