In her memoirs, a Jewish artist named Rosemarie Koczy, pictured above, claimed to have survived two concentration camps during the Holocaust.

Upon closer scrutiny, however, her life story contained a few inconsistencies. For one, she wrote that the Nazis deported her to the Traunstein subcamp of Dachau, a place for male prisoners.

Rosemarie, biologists later confirmed, was female.

Just because one Holocaust survivor lied about her life, though, doesn’t mean that the millions of other ones also did.

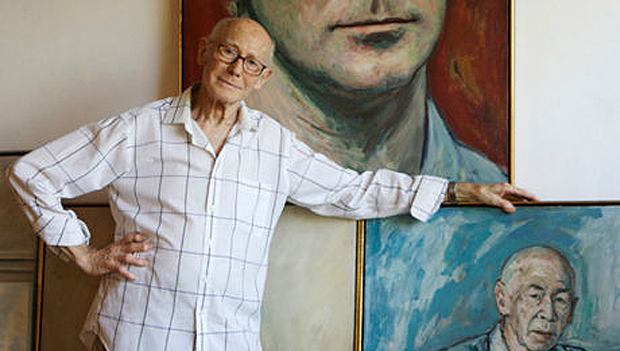

I mean the story of 93-year-old Kalman Aron, another Jewish artist who survived more than one concentration camp, contains no inconsistencies whatsoever.

Kalman Aron began drawing pencil and crayon portraits of his family in Latvia when he was 3. A child prodigy, he mounted his first one-boy gallery show when he was 7. He was commissioned to paint the official portrait of the Latvian prime minister when he was 13. He enrolled at an academy of fine arts in Riga, the capital, at 15.

Then, in 1941, when he was 16, the Germans invaded, and his parents, who were Jewish, were murdered. But Kalman’s artistic talent would spare his life. Over the next four years, he would survive seven Nazi concentration camps by swapping sketches of his captors and their families for scraps of food.

…

After the German invasion, Kalman’s father was conscripted for a work detail and never seen again. Kalman was herded into Riga’s Jewish ghetto with his older brother and his mother. She was murdered later that year in the massacre of 25,000 Jews near the Rumbula forest.

Kalman was shipped to perform slave labor in camps in Latvia, Poland, Germany (where he was sent to Buchenwald) and what was then Czechoslovakia.

Seven camps, eh? These weren’t concentration camps to this guy – they were motels!

Seven isn’t the high score, though. That honor goes to Chaim Ferster, who survived eight of them.

(UPDATE: Chaim was beaten by Elias Feinzilberg, who survived nine.)

It’s still an impressive achievement for a man, especially considering that one of those camps was the notorious Buchenwald camp in Germany.

Buchenwald didn’t have gas chambers (that was more of a Poland thing), but it did have something almost as bad: execution rooms where innocent Jews were hung from meat hooks:

The guards at Buchenwald, known for their efficiency, hung Jews to death because they thought bullets were too slow.

After Nazi guards discovered his artistic ability, he would be temporarily relieved of hard labor and hidden away in a barracks to sketch their portraits or copy photographs of their families. He might be rewarded with a moth-eaten blanket or a morsel of food.

“They wouldn’t pay me anything, but I would get a piece of bread, something to eat,” he was quoted as saying last year in The Jewish Journal. “Without that, I wouldn’t be here.”

“I made it through the Holocaust with a pencil,” he told Steven C. Barber, who is adapting Ms. Magee’s book into a documentary, “Into the Light,” for Vanilla Fire Films.

Hmm.

You know, those Nazis seemed rather lenient at times. These people were supposedly dedicated to the complete extermination of the Jewish race, yet they were always willing to spare the lives of Jews that exhibited even the most modest of talents.

Is it possible that the Nazis weren’t as two-dimensionally evil as the court historians led us to believe?

I’m tempted to respond with “yes” like an anti-Semite.

But then I remember Schindler’s List and come to my senses. Of course they were evil – survivors like Kalman Aron were the exception, not the rule.

The rule was the Six Million.