Diversity Macht Frei

March 12, 2016

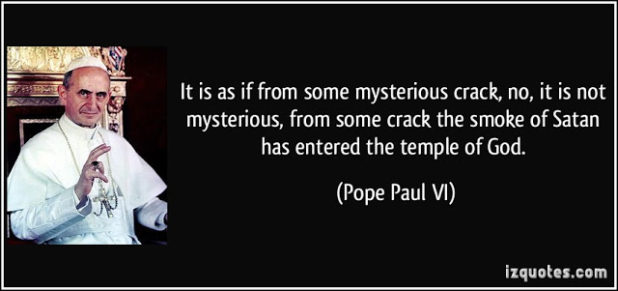

In 1972, Pope Paul VI made an extraordinary remark that drew worldwide attention. He said that the “smoke of Satan has entered the sanctuary of God”, meaning the Catholic church. I can’t help wonder whether, in uttering these words, he was making a regretful admission of guilt on his own part. Because it was under his auspices, in 1965, that the church issued a document called Nostra Aetate, which reversed most of the church’s key and time-honoured teachings on Jews. Overnight, the virile antisemitism of the old Catholic doctrine was replaced by a weak and neutered philosemitism. The Catholic church, one of the Jews’ traditional adversaries, had been taken out of the game. And it happened through infiltration.

BEGIN CITATION

…the church had never in its history looked upon the Jews in the ways specified in Nostra Aetate. A second pioneer in the Christian-Jewish dialogue, the American Paulist Father Thomas Stransky of Milwaukee, who helped draft Nostra Aetate as an advisor at Vatican II, makes the point more radically. The Declaration signaled a “180 degree turnabout,” he said in a speech of 2006, reversing all that the church had thought about Jews since its early days, a time when teachings about Christ’s divinity or the Trinity had yet to be formulated. From the third century at the latest, church authorities taught that the Jews’ destiny was to wander the earth suffering retribution from God for rejecting Christ, serving in their destitution as the most direct evidence that the church’s claims to God’s favor were correct. By acts of discrimination passed by councils through the centuries, the church then created conditions calculated to keep the Jews destitute. This situation was supposed to endure until the end of time when the Jews finally turned to Christ.

The teaching of Vatican II could not have been more different. Beyond saying that the promises— thus the Covenant— made by God with the Jews were still in force, the document asserted— quoting St. Paul’s letter to the Romans— that the Jews remained “most dear” to God. That is, they continued to enjoy God’s favor. This radical shift in teaching worried many, including Father Stransky, who wondered whether Catholics could suddenly assimilate ideas that contradicted everything they had been taught to believe. Yet in 1965, despite insistent urging from the personal theologian of Pope Paul VI, the drafters of Nostra Aetate refused to say that the church must conduct a mission to the Jews, or that the Jews must turn to Christ.

In the statement that the bishops overwhelmingly accepted and Paul VI promulgated as authoritative church teaching— teaching that cannot be rescinded by later popes— the drafters likewise ignored other sections of scripture suggesting that Jews were responsible for Christ’s death (Acts 3: 15) and lived under a curse (Matt. 27: 25), and that the covenant God had made with the Jews was obsolete (Heb. 8: 13). Instead, they shifted the church’s understanding of its relation to the Jews to three chapters of Paul’s letter to the Romans, which contain the Apostle’s most mature reflections on the Jewish people.

…the pages that follow trace the Declaration’s origin from the intellectual milieu out of which this shift to Paul occurred, namely, groups of Catholic anti-Nazis operating in Central Europe in the 1930s. Among them was one of Nostra Aetate’s authors, the priest Johannes M. Oesterreicher, originally a Jew from Moravia, who served as theological consultant at the Vatican Council, but began his struggle against antisemitism in Vienna in 1933. Oesterreicher worked within tiny groups of Catholics who published and spoke out against Nazi ideology from cities just beyond Hitler’s reach, first in Austria and Switzerland, and then France until the German attack in 1940.

At that point, Oesterreicher joined a number of his comrades-in-arms— the philosophers Jacques Maritain and Dietrich von Hildebrand, the political scientist Waldemar Gurian— in exile in the United States. Other collaborators stayed behind in Europe. Oesterreicher’s intellectual sparring partner for three decades, the German theologian Karl Thieme, took refuge near Basel, Switzerland, in 1934, and remained there through the dark war years, continuing to think and write about Christian-Jewish relations.

The theologian Annie Kraus, a Jew who became Catholic in 1942 and inspired Oesterreicher and Hildebrand with pathbreaking thought on antisemitism written in 1933, hid from the Gestapo first in Berlin, then Southern Germany. Others were not so lucky. The priest who baptized Kraus and Oesterreicher, peace activist Max Metzger, was tried and executed for treason in Berlin in 1944. A year earlier the Gestapo arrested Ferdinand Frodl, a Jesuit who wrote about racism for Dietrich von Hildebrand.

…Why the activists surrounding Johannes Oesterreicher got involved in fighting Nazi racial antisemitism is a question of personal biography that we ultimately cannot answer. Yet one fact stands out in their histories: they were converts. This trend did not begin in 1933. From the 1840s until 1965, virtually every activist and thinker who worked for Catholic-Jewish reconciliation was not originally Catholic. Most were born Jewish. Without converts the Catholic Church would not have found a new language to speak to the Jews after the Holocaust.

As such, the story of Nostra Aetate is an object lesson on the sources but also the limits of solidarity. Christians are called upon to love all humans regardless of national or ethnic background, but when it came to the Jews, it was the Christians whose family members were Jews who keenly felt the contempt contained in traditional Catholic teaching. A group called Amici Israel, which emerged in the 1920s at the initiative of the Dutch convert Franziska van Leer, demanded an end to liturgical references to Jews as perfidious and a halt to efforts to “convert” the Jews.

After the war, a new generation of converts joined Oesterreicher (now known as John) and Karl Thieme in their efforts to undo the anti-Judaism on which antisemitism thrived. In Freiburg, Germany, the concentration camp survivor Gertrud Luckner published the Freiburger Rundbrief and enlisted Thieme as her theological advisor. There Thieme developed ideas later taken into the documents of Vatican II. In Paris, Father Paul Démann, a converted Hungarian Jew, began publishing the review Cahiers Sioniens, and, with the help of fellow converts Geza Vermes and Renée Bloch, refuted the anti-Judaism in Catholic school catechisms, especially the idea that Jews lived under a curse. Three years later Miriam Rookmaaker van Leer, likewise a convert (from Protestantism), founded the Dutch Catholic Council for Israel (Katholieke Raad voor Israel), and engaged the priest Anton Ramselaar as her theological advisor. Ramselaar had known the founders of the Amici Israel initiative of the 1920s.

In 1958, Ramselaar, at the suggestion of Ottilie Schwarz (a convert from Vienna) convened an international symposium in Apeldoorn, Holland which brought together the leading Catholic thinkers from France (Paul Démann), Germany (Karl Thieme, Gertrud Luckner), Israel (Abbot Leo Rudloff, Father Jean-Roger Hené), the United Kingdom (Irene Marinoff), and the United States (John Oesterreicher). Besides Ramselaar, all were converts. At its third meeting, in 1960, this group produced theses that were passed onto the new Pope John XXIII— along with recommendations of John Oesterreicher’s Institute for Judeo-Christian Studies at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey. Oesterreicher founded this institute in 1953 with help from the eminent Chinese legal scholar John C. H. Wu, professor at Seton Hall and a convert to Catholicism. 8 In 1961, Oesterreicher went on to the Second Vatican Council. At one critical moment in October 1964, the priests Gregory Baum and Bruno Hussar joined Oesterreicher to draft the statement that would become the Vatican Council’s decree on the Jews. Like Oesterreicher, Baum and Hussar were converts of Jewish background.

END CITATION

Source: From Enemy to Brother by John Connelly