Diversity Macht Frei

December 29, 2018

It’s not enough to wipe white people out genetically. It’s not enough to deny them their own space in which to continue their existence. You have to obliterate any sense of pride in their ancestors’ achievements and instil a sense of shame and guilt in them even when they are doing something as innocent as viewing a work of art.

Our encyclopedic museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art are vocally committing themselves to diversity and inclusion, and enacting major changes to the way they tell the story of world art. In many ways, however, Europe is still firmly fixed at their centers. I work in a large encyclopedic museum, where I curate shows and displays in a collection of European art. Amidst a surge in white supremacist violence in my community and across the country, I believe the time has come to reconsider how American museums are presenting European art.

European painting and sculpture has formed the core of our museums since they were founded. These works usually inhabit the largest and most central galleries in buildings that are themselves European in style, modeled after the great royal and imperial collections of England, France, and Germany. Because the centering of Europe is baked into the architecture of these institutions, some may not see the connection to white supremacy today. But white supremacists do. Europe’s cultural prestige is their evidence for the racial superiority of white America.

The author is one Alexander Kauffman. Kauffmann (with its spelling variants) is a typically Jewish name, which means “Merchant” in German. This Kauffman is an Unhappy Merchant. He’s unhappy because white people who don’t want to become an ethnic minority in their own land (aka white supremacists) point to their artistic heritage as an example of what will be lost if the brown horde swamps the citadel of light.

Consider the recruitment materials that white supremacist groups distribute. One video starring Richard Spencer cycles through images of European paintings and monuments as he intones: “We aren’t just white. White is a checkbox on a census form. We are part of the peoples, history, spirit, and civilization of Europe.” Joining Spencer at the 2017 Unite the Right Rally was the white nationalist group Identity Evropa. They assert the superiority of “European, non-Semitic heritage” and advocate ending immigration to the United States to maintain the “European-American supermajority.” They recruit primarily on college campuses and use imagery of Renaissance sculptures emblazoned with calls to “Protect your heritage” and “Serve your people.” A March 2018 rally on the steps of Nashville’s replica of the Parthenon featured a 40-foot banner: “European Roots/American Greatness.” Far-right Twitter and Reddit also proudly claim 19th- and 20th-century European art, but tend to lose interest around the end of the Second World War. As neo-Nazi site The Daily Stormer tells it, with the Allies’ victory, “the West’s cultural evolution was also completely upset. In practically every way, the art produced today is inferior to European art thousands of years old.”

In the cities where today’s white supremacists are organizing, museum galleries are the places where Europe’s cultural patrimony is most visibly singled out as exceptional. The white supremacists have noticed. In February of last year, one group gathered at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Lingering in a room of 18th-century French armchairs and English landscapes, they were confronted by anti-fascist activists, then threw punches and were ejected. They had come to the museum for a “white lives matter” rally. Organizers later explained that they chose that location in order for participants to “enjoy the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s collection of traditional art.”

What can be done to beat down White Pride?

After the violence in Charlottesville, Charleston, and Pittsburgh, our encyclopedic museums must take steps within their galleries of European Art to combat white supremacist ideology.

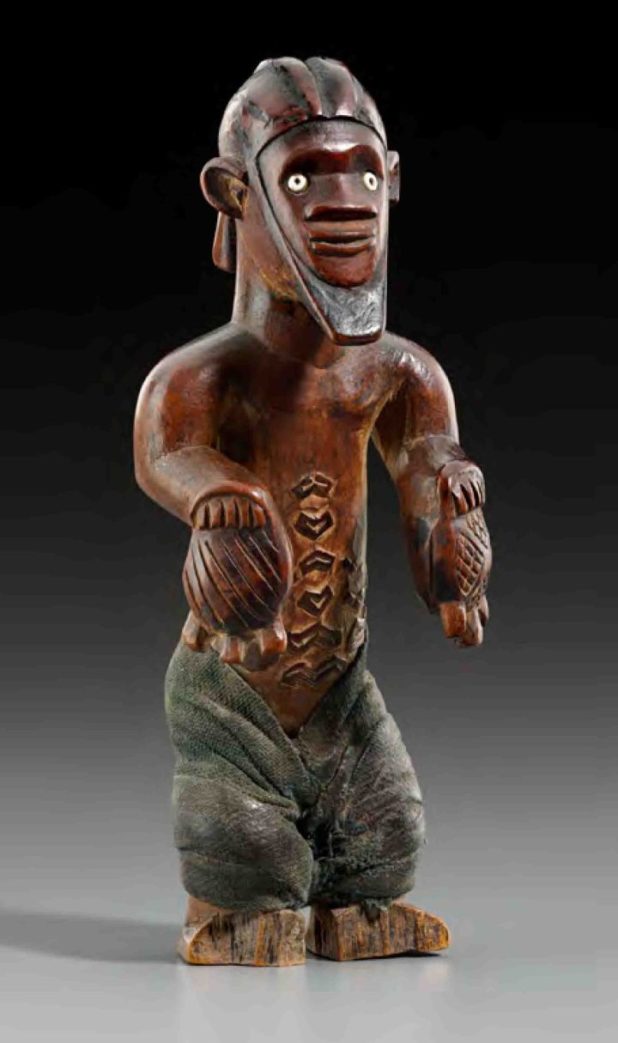

Show more low-grade art from brown people and pretend it’s actually good.

“Globalization,” “interconnectivity,” and “diversity” are more than museum “buzzwords”; they are the battles white supremacists are fighting. Thankfully, the Met and other major encyclopedic museums are enacting change: exhibiting and commissioning more work by contemporary artists from historically underrepresented groups; expanding their collections and galleries of historical African, Asian, and Latin American art; and better representing indigenous and immigrant artists in their historical American galleries.

Deny white people really exist except when they’re the objects of attack. When they seek to mobilise in their own defence, break them down into micro-communities incapable of rallying for collective action or pride.

Disrupt the mythos of a singular triumphant civilization encompassing all of Western Europe and extending from Ancient Greece to today. Our grouping of French, British, German, Italian, and Spanish art in suites of “European” galleries, usually the most prominent in the museum, supports a historical fiction present in white nationalists’ claims of racial superiority and in their aggrievement towards globalization: that of a world dominant civilization unified by a shared racial identity. Against the fantasy of commonality within “Fortress Europe,” we must learn how to tell the story of Europe’s historical disharmony and integration in global geographies of empire, trade, and migration.

Dredge up any residues of “diverse people” we can find in the collections, hitherto left unremarked because their art was unremarkable. The bonus points from diversity make it worthy of exhibition.

Challenge the notion that the cultural life of Europe was uniformly white, heteropatriarchal, and Christian. Jews, Muslims, women, queer people, and people of color pervade the history of European art. After centuries of minimization, we must call attention to their presence. In many cases, our collections already include works that allow us to do so, but they are isolated in Judaica or Islamic galleries, or more often, languishing in storage. A label on a wall can also state what is not there. We should talk about absences. The uniformity of our art history is not the natural order of things, or even historically accurate. There were women artists. American museums did not collect them.

“There is no art from People of Mud, Muslims, Jews or women on on this wall because our ancestors, who acquired the objects in this collection, had more sense than we did and recognised lack of artistic merit when they saw it.”

A layer of politically correct commentary also needs to be imposed on the art.

Speak plainly about the values of the art we exhibit. Celebrate those works that are committed to values we share, and acknowledge those that are not. This does not mean avoiding or minimizing complexity in the artwork we exhibit, but rather learning how to talk about it better, more directly. In my own area of expertise, modern art, there was an outpouring of new work between the two world wars attacking European nationalism, colonial expansion, and restrictive gender roles. Too often we shy away from explicitly stating the political and social values in these works, preferring vague references to their “radicalism” or “avant-gardism.” If a painting targets fascism, this should be made clear in the wall label. If its creation resulted in the artist being targeted and killed by the Nazi party, this should be stated too. And if that same painting, or another, employs misogyny or racist fantasies of Black primitivism, this too must be stated.

Tell the histories of our collections. In November, Decolonize This Place activists occupied the Egyptian galleries at the Brooklyn Museum with a banner reading, “How was this acquired? By whom? For whom? At whose cost?” Visitors to European art collections have the same questions. Few know why paintings from European royal collections are in their cities. Our silence on this matter promotes the idea of America’s natural inheritance of European culture.

And, of course, we must hire more low-talent brown people who would otherwise be unable to gain employment on the strength of their personal merits alone.

Finally, and most importantly, we must address the inequities in the staffing and leadership of curatorial departments of European Art. The overwhelming whiteness of staff is a challenge to inclusion efforts across the museum sector, but it is a particular problem in the curatorial ranks and in encyclopedic museums. In the most recent demographic data, 90 of America’s top encyclopedic art museums reported employing an aggregate curatorial staff of 730 people. Of those 730 people, only 11 were Black. 634, or 86%, were white. Art museums’ professional and grant-giving organizations are aware and devoting substantial resources to addressing systemic causes. To my knowledge, there is no effort specifically directed towards diversifying European Art, which is regularly among the least diverse spaces in already majority-white institutions — the least diverse along virtually every axis: socio-economic background, religion, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation.

What we are faced with truly is the most systematic effort at genocide the world has ever seen. Every manifestation of a people’s existence, must be attacked and undermined.

Some of these changes are already happening in European art departments, at the Met and at museums across the country. But as a professional body, European art has sat on the sidelines of museum efforts toward diversity, equity, and inclusion for too long. We must energetically join our colleagues who have been doing this work for decades, show them we stand in solidarity and support, and seek out and listen to our critics. They inspire the recommendations here. Museums are not neutral. Displays of European Art are not neutral. White supremacists know it. We must see it too.

The author, Alex Kauffman, has declared his willingness to answer your questions. So if you have any, fire away. Judging by the timbre of his voice, he would probably qualify for diversity inclusion under the “non-hetero-normative” box.

Alexander Kauffman our Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow and #Duchamp expert is here to answer your questions. #AskACurator pic.twitter.com/aRSwNzgcne

— Philadelphia Art Museum (@visitpham) September 12, 2018