Paul Nachman

VDARE

November 4, 2015

VDARE.com’s John Derbyshire has recently done send-ups (here and here) of what he calls the “Magic Dirt” theory of differential performance between disparate groups of humans. As he explained it on November 1,

The core idea is that one’s physical surroundings—the bricks and mortar of the building you’re in, or the actual dirt you are standing on—emit invisible vapors that can change your personality, behavior, and intelligence.

Thus, for example, observed differences in economic mobility between Charlotte and Salt Lake City must arise from some otherwise-undetectable differences in these locales—rather than from their obvious (but unmentionable) demographic differences.

Of course, Salt Lake City and Charlotte are separated by about 2,000 miles, and it seems likely that the dirt is pretty different between them, so perhaps we can’t, as a matter of logic, completely eliminate magic associated with the dirt as the explanation for city-to-city differences in their human populations’ outcomes.

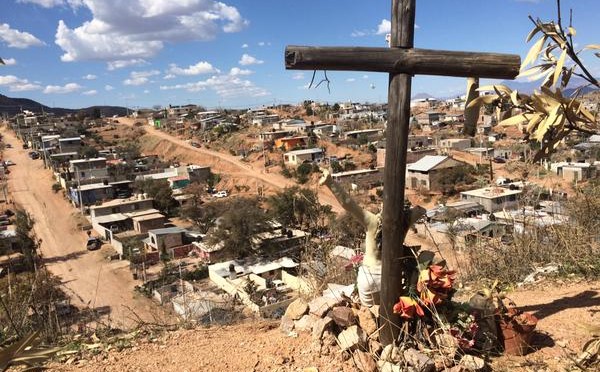

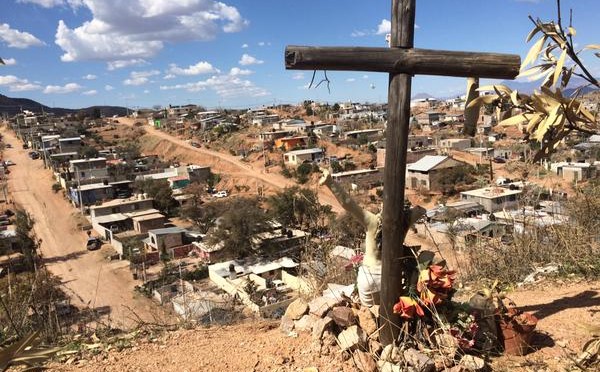

Instead, then, let’s consider the ideal control experiment, where the dirt is the same yet the civilizational differences are stark: Nogales, Sonora, Mexico versus Nogales, Arizona, U.S.A..

In its July, 1998 issue, The Atlantic Monthly’s veteran foreign correspondent Robert D. Kaplan described the contrast between these two cities, which abut each other at the international border. An excerpt:

I had crossed the Berlin Wall several times during the Communist era. I had crossed the border from Iraq to Iran illegally, with Kurdish rebels. I had crossed from Jordan to Israel and from Pakistan to India in the 1970s, and from Greek Cyprus to Turkish Cyprus in the 1980s. In 1983, coming from Damascus, I had walked up to within a few yards of the first Israeli soldier in the demilitarized zone on the Golan Heights. But never in my life had I experienced such a sudden transition as when I crossed from Nogales, Sonora, to Nogales, Arizona.

Surrounded by beggars on the broken sidewalk of Mexican Nogales, I stared at Old Glory snapping in the breeze over two white McDonald’s-like arches, which marked the international crossing point. Cars waited in inspection lanes. To the left of the car lanes was the pedestrian crossing point, in a small building constructed by the U.S. government. Merely by touching the door handle one entered a new physical world.

The solidly constructed handle with its high-quality metal, the clean glass, and the precise manner in which the room’s ceramic tiles were fitted — each the same millimetric distance from the next — seemed a marvel to me after the chaos of Mexican construction. There were only two other people in the room: an immigration official, who checked identification documents before their owners passed through a metal detector; and a customs official, who stood by the luggage x-ray machine. They were both quiet. In government enclosures of that size in Mexico and other places in the Third World, I remembered crowds of officials and hangers-on engaged in animated discussion while sipping tea or coffee. Looking at the car lanes, I saw how few people there were to garrison the border station and yet how efficiently it ran.

…

[In Nogales, AZ, the] billboards, sidewalks, traffic markers, telephone cables, and so on all appeared straight, and all the curves and angles uniform. The standardization made for a cold and alienating landscape after what I had grown used to in Mexico. The store logos were made of expensive polymers rather than cheap plastic. I heard no metal rattling in the wind. The cars were the same makes I had seen in Mexico, but oh, were they different: no chewed-up, rusted bodies, no cracked windshields held together by black tape, no good-luck charms hanging inside the windshields, no noise from broken mufflers.

…

The Plaza Hotel in Nogales, Sonora, and the Americana Hotel in Nogales, Arizona, both charged $50 for a single room. But the Mexican hotel, only two years old, was already falling apart—doors didn’t close properly, paint was cracking, walls were beginning to stain. The American hotel was a quarter century old and in excellent condition, from the fresh paint to the latest-model fixtures. The air-conditioning was quiet, not clanking loudly as in the hotel across the border. There was no mold or peeling paint in the swimming pool outside my window. The tap water was potable. Was the developed world, I wondered, defined not by its riches but by maintenance?

As I walked around Nogales, Arizona, I saw a way of doing things, different from Mexico’s, that had created material wealth. This was not a matter of Anglo culture per se, since 95 percent of the population of Nogales, Arizona, is Spanish-speaking and of Mexican descent. Rather, it was a matter of the national culture of the United States, which that day in Nogales seemed to me sufficiently robust to absorb other races, ethnicities, and languages without losing its distinctiveness.

The people I saw on the street were in most instances speaking Spanish, but they might as well have been speaking English. Whether it was the quality of their clothes, the purposeful stride that indicated they were going somewhere rather than just hanging out, the absence of hand movements when they talked, or the impersonal and mechanical friendliness of their voices when I asked directions, they seemed to me thoroughly modern compared with the Spanish-speakers over in Sonora. The sterility, dullness, and predictability I observed on the American side of the border — every building part in its place — were signs of economic efficiency.

…

In Mexico the post offices looked as if they had just been vacated, with papers askew and furniture missing. In Nogales, Arizona, the Spanish voices in the post office were the last thing I noticed; what struck me immediately was the evenly stacked printed forms, the big wall clock that worked, the bulletin board with community advertisements in neat columns, the people waiting quietly in line, and a policeman standing slightly hunched over in the corner, carefully going through his paperwork, unlike the leering, swaggering policemen I had seen in Mexico.

The silent streets of Nogales, Arizona, with their display of noncoercive order and industriousness, cast the United States in a different light not only from Mexico but from many of the other countries I had seen in my travels. Nogales, Arizona, demonstrated just how insulated America has been — thus far, at least.

[From Travels Into America’s Future: Mexico and the Southwest]

I expect that many of us at VDARE.com would disagree with Kaplan’s interpretation that what he saw in Nogales, AZ “was not a matter of Anglo culture per se,” but that doesn’t detract from his straight reportage on the contrast between the two cities.

In short (and plagiarizing some verbiage from letter-writer extraordinaire Tim Aaronson), the difference between these American and Mexican “twin cities” straddling the border is like night and day, yet the land is obviously the same. So it’s not the dirt that’s important, it’s the people. Put another way, if culture didn’t matter, Mexico and Central America would be paradise.