Silas Reynolds

The Right Stuff

June 2, 2016

Far more common in the world of comic books is the sight of the Punisher acting as racial purist, killing a black or Hispanic mugger/rapist in an alley after the grotesque criminal accosted a pretty white woman at the point of a switchblade.

– War, Politics and Superheroes: Ethics and Propaganda in Comics and Film

I used to read comic books when I was a kid. My father would allow me to grab one or two off the rack at the grocery store or local pharmacy. They were fun and harmless, but I stopped reading them when I grew up–as should all boys when they transition to young adulthood. But my favorites were Batman, Wolverine and The Punisher–comics that even in the early and mid-1990s were fairly dark. I didn’t read too much into them, I just liked the grim action and adventure. Batman was always great and I enjoyed the cartoon Batman: The Animated Series. Wolverine and The Punisher were somewhat violent adventure yarns, akin to a macho 1980s action film.

A few years ago, I decided to kill some time (waiting on a woman, naturally) in a comic book store within an outdoor mall in upscale Northern Virginia. I hadn’t been in a comic book store in about a decade and it was much different from when I was a kid. The main difference being that there weren’t any kids in the store–certainly, no one younger than 15. In my youth, a comic book store was usually managed by a middle-aged overweight nerd with some posters on the walls and large musty boxes full of plastic wrapped comics; children or teenagers would be milling around and filtering through the boxes looking for their favorite titles. This store was different. It was staffed by twenty-something tattooed and multicolor-haired hipsters, toys (likely not meant for children) were on display behind glass cases, a whole section was devoted to literature (not comics) on superheroes and Japanese cartoons; young men sat Indian-style on the floor reading “graphic novels.” A place which was historically meant for children, seemed to have transformed into an asylum for maladjusted and socially retarded virgins.

I found the actual comics in a smaller section. I got embarrassed just being in the store after a few minutes and grabbed a copy of The Punisher after quickly thumbing through it; I paid and left. When I got back to my car and took the time to actually read it–I was shocked. Not because of the violence, which was so intense it would make hack director Quentin Tarantino blush, but the amount of red pills sprinkled throughout the story. A dindu with gold plated teeth made a white hooker give him a blowjob and then he killed her in a fit of rage. A former SWPL turned junkie was “turned out” and anal raped by a pack of dindu hoods. Commentary about the softness of society, law enforcement’s failure at deterring crime and the ugliness and immorality of criminality were peppered throughout the comic. And, throughout the story, the Punisher eviscerated thugs, rapists and lawbreakers with a mix of righteous violence and hardcore gore. As Ta-Nehisi Coates would say, the Punisher stood on a mound of mutilated black bodies. I’m not a comic book fan, but after reading it, I felt a deep sense of adoration and admiration for Marvel’s one-man right wing death squad.

The character was created by goys, writer Gerry Conway and artist John Romita, Sr., with publisher and crypto-Jew (((Stan Lee))) (born Lieber) green-lighting the name. Although the Punisher debuted as a villain in 1974’s The Amazing Spider-Man, Frank Castle, alias the Punisher, quickly became an anti-hero whose popularity revealed a collective reactionary, and I would argue fascist, turn in the late 1970s and early 1980s. After his family was murdered in New York’s Central Park, the Punisher, a gun-toting Vietnam veteran and a synthesis of all the then popular vigilante film tropes, is a ruthless killer who wages an obsessive one-man war on crime. He also annoys more traditional superheroes like Daredevil and Captain America, who do not kill their adversaries. Originally written as a minor character, the Punisher became a reoccurring figure in many Marvel titles because fans demanded it–on an instinctual level, both those on the Right and, not all that surprisingly, on the Left–desired more of Frank Castle’s exploits at butchering criminality. Eventually, the character received his own series and continues in print today and maintains a vigorous, albeit cultish, popularity.

Intellectual commentary on the Punisher has addressed the character’s psychological temperament (as a general rule, the Punisher seems at his most insane whenever he meets another superhero and argues over their position on the death penalty) and his role in the Marvel universe. But politically, the Punisher is, like fascism, completely reactionary. He falls in the same realm as the stories about Vietnam veterans, much like John Rambo, who were abandoned by their own country and who brought the war (and trauma) back home. The Punisher is also a natural reaction to the failure of crime that plagued our cities in the 1970s and 1980s and is a natural fit to the heroes of such outstanding films as Dirty Harry and Death Wish–both films which were labeled as fascist at the time of their release.

The Punisher, generally speaking, since writers and artists do vary over the decades, is clearly an inspiring fascist characterization. Frank Castle views the world in complete binary–good versus evil or black versus white. There is no grey area or morally ambiguous scenario for the Punisher. If something is wrong, it must be punished swiftly–and with extreme prejudice. Fascism not as a historical political platform, but as a general and current ideology can, at times, be difficult to articulate. However, Umberto Eco, whom I’ve mentioned before when examining the literary James Bond, wrote a 1995 essay titled “Eternal Fascism.” In it Eco lists 14 general properties of fascist ideology and argues that it is not possible to organize these into a comprehensible system, but that “it is enough that one of them be present to allow fascism to coagulate around it.” One of the main items that clearly resonate with the Punisher is the second item on Eco’s list: “The Cult of Action for Action’s Sake,” which dictates that action is of value in itself, and should be taken without intellectual consideration or in his words “reflection.” Eco is no fascist and his essay, while somewhat accurate, is a negative critique of fascism. Eco is correct that fascists worship “action,” in the abstract sense of the word, but it is not without intellectual reflection–more properly, it is decisive action that is key. Eco’s use of “intellectual reflection” is simply sophistry and, without decisiveness, the results are half-measures and stopgaps–which is why the United States is quickly morphing into a Third-World hellhole.

Another aspect of fascism that Eco explores is the nature of life and warfare and, for the Punisher, life is a constant state of warfare. For the Punisher, and fascism, there is no struggle for life but, rather, life is lived for struggle. Or, in Eco’s words, “thus pacifism is trafficking with the enemy” and it is bad because life is permanent warfare. Il Duce once said, “War is to man what maternity is to the woman,” and the Punisher’s singular purpose in life is warfare. In fact, the Punisher’s motto, in both the 2004 Thomas Jane film and the 1994 comic book line The Punisher: Year One, is the Latin phrase, Si vis pacem, para bellum or “If you want peace, prepare for war.” And Frank Castle’s war is a never-ending scorched-earth no-quarter-given crusade on crime.

And speaking of fascism and crime, that is where political scientist Lawrence W. Britt comes in. Britt studied Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, Franco’s Spain, Salazar’s Portugal, Papadopoulos’s Greece and Pinochet’s Chile. Like Eco, he correlated 14 characteristics, common to them all, that define them as fascist regimes. One in particular that connects to Marvel’s inspirational fascist is the “Obsession with Crime and Punishment”–and that, under fascist regimes, the police are given almost limitless power to enforce laws, the people are often willing to overlook police abuses, an intensification in the severity of punishment and the increased use of the death penalty or, as prominent jurist Hans Frank once proudly boasted, the “reckless implementation of the death penalty.” And, the Punisher almost exclusively implements the death penalty to criminals. An editor at Marvel recently revealed that between the mid-1970s and 2011 the Punisher was responsible for the deaths of 48,502 people.

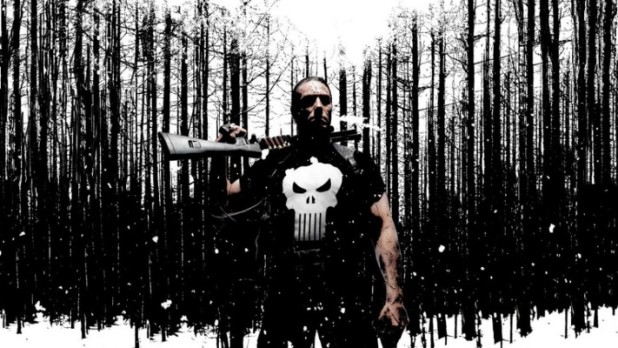

Not surprisingly, the Punisher aesthetically illuminates a fascist appearance. Captain America, like many fictional and real-life Marvel connections, is generally disgusted by the Punisher’s Weltanschauung and has actually referred to him as a “fascist,” noting the resemblance of the Nazis’ predominant colors (black) and symbolism (skulls) to the Punisher’s uniform. Punisher artist Russ Andru underscored the fact that the Punisher was different from other costumed heroes–rather than wearing a colorful outfit, the Punisher was garbed in a black uniform that featured an enormous white skull image and a fully stocked ammunition belt; the white boots and white gloves he wore neatly symbolized the dualistic, black-and-white nature of his thinking, and added a somewhat implausible note of visual contrast.

Similar to the anti-heroes of noir films and gritty Westerns, the Punisher exists on the fringe of both the community and the wilderness–operating for the most part in our decayed urban zones, where he is likely to remain until he dies. Frank Castle is just one of the long line of armed men who has to pick up the mantle of justice when regular law enforcement fails. What makes the Punisher exceptional is his mindset–he rejects compromise, negotiating, logrolling, dealmaking, easy living and empty rhetoric–as well as, the scale and duration of his war. Few fictional noir private-eyes or sixgun shooters could possibly contend with the Punisher’s record of achievement in this area.

Make no mistake though, liberals despise the Punisher, even if they somewhat agree with his purpose. Empire’s Owen Wilson illustrates this hidden appreciation for Frank Castle by writing in January of this year, “Commentators often like to call him “morally ambiguous”. There’s nothing ambiguous about him: he’s a reprehensible fascist. What’s ambiguous is our response to him, which treads that queasy line between repugnance and the visceral knee-jerk satisfaction of seeing bad guys shot in the face.” Most Punisher comics strive for a realism and appear to approve the Punisher’s actions, which rankles many shitlib fanboys. For instance, Marc DiPaolo–his book is quoted at the beginning of this piece–finds racist suggestions in the Punisher comics as a whole and, “No matter how many Waspish U.S. senators he assassinates for political corruption, the Punisher seems most ecstatic when he breaks into a warehouse and begins machine gunning legions of Italians, Japanese ninjas, and nonwhite foes with gold teeth.”

The director of the Avengers films and feminist pushover, Joss Whedon, has said of Frank Castle, “Here’s why I’m not running Marvel: If I was, I would kill the Punisher. I don’t believe in what he does. The Punisher just shoots up places. And if you’re telling me he’s never hit an innocent, then I’m telling you, that’s fascist crap.”

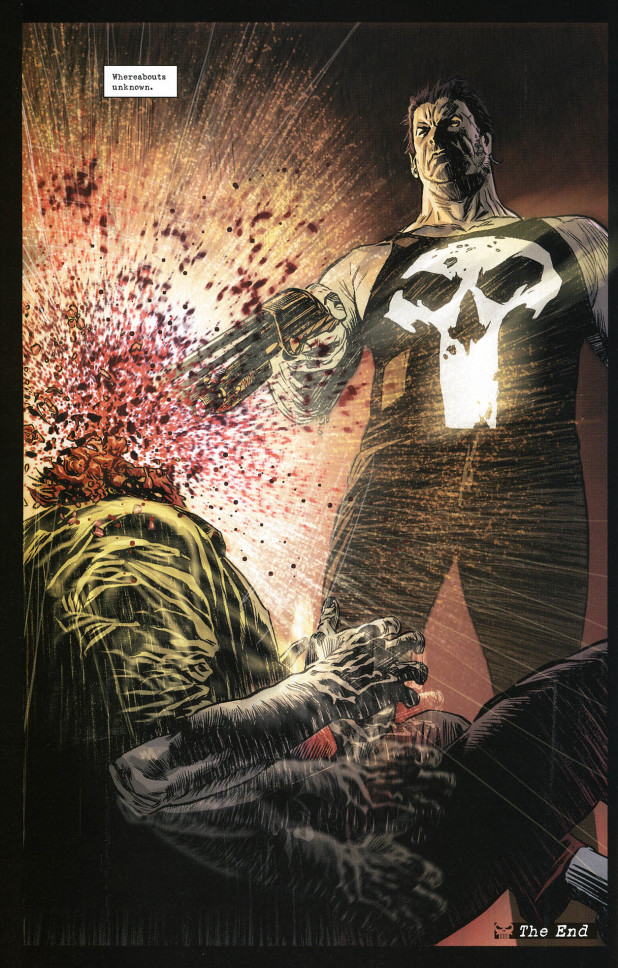

The Punisher, the cold blooded fascist, would have only one response for Joss “Equality Now” Whedon:

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History