Daily Mail

November 13, 2013

Lieutenant Dwight McKay was a long way from Chicago. To be precise, he was 4,436 miles away, stuck in a room in a castle in the middle of Germany, sitting opposite a nervous and bespectacled man who, at 49, was nearly 20 years his senior.

The man looked like an academic, which, in a previous life, was what he had been. In fact, Dr Hildebrand Gurlitt was one of the most respected art experts and curators in Germany, the product of a supremely talented family that could boast artists and musicians stretching back for many generations.

McKay was not of such an artistic bent. He had graduated from law school in 1939, but before his career could get under way, America’s entry into the war in 1941 had seen him drafted into the army.

With his legal background, McKay was assigned to the Judge Advocate’s Section of General Patton’s 3rd Army as a war crimes investigator.

Since the invasion of Normandy exactly a year before in June 1944, McKay had been hunting down those who had taken part in atrocities. However, for the past month, his section had been investigating German art looting.

McKay and his comrades had been tipped off about Gurlitt and told he had a ‘red flag’ next to his name.

That meant one thing — Dr Gurlitt was a suspected looter. The Americans had seized 139 paintings, drawings and sculptures from him that appeared to prove it.

Though the interrogation lasted for three days, its consequences have continued for many decades.

Just last week, they came spectacularly to a head, with the revelation that Cornelius, the 79-year-old son of Hildebrand Gurlitt, has been found to have been hoarding 1,401 artworks worth an estimated £1 billion at his home in Munich.

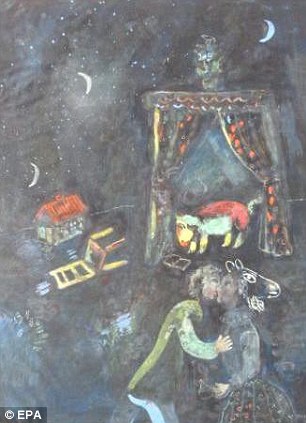

Yesterday, the German authorities released an initial list of just 25 works from the huge collection, including Matisse’s The Seated Woman and Chagall’s Allegory.

Since the discovery, many have believed Cornelius had committed suicide, but this week he broke cover and was spotted by French journalists in a Munich shopping centre.

When confronted, his reply was cryptic. ‘Approval that comes from the wrong side is the worst thing that can happen,’ he said.

Yesterday morning, Gurlitt was seen taking a taxi to the airport with an unidentified woman. Typically for this secretive old man, no one knows where he is heading.

All he said to photographers was: ‘All this is a great villainy.’

In a way, he was right to describe the affair in such a way, because the story of how this incredible collection ended up in the hands of an eccentric recluse and hidden behind piles of rotting food in a dingy flat is essentially a tale of theft and deceit on a grand scale.

This week, I was able to unearth some formerly top-secret U.S. government documents that allow us to draw a direct line from the chaos of post-war Germany to the strange world of a weird old man almost all of whose life has been defined by keeping the world’s greatest art collection a total secret.

More disturbingly, the story of the Gurlitt Hoard also reveals how Hildebrand ran rings around Allied investigators who never realised the true nature and scale of his ill-gotten haul — and handed back most of what they confiscated from him.

These investigators included the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives section, better known as the Monuments Men, whose heroics are depicted in a movie of the same name starring George Clooney and Hugh Bonneville, which premieres in just a few weeks.

To understand the story, we must go back to September 15, 1895, the birth date of Hildebrand Gurlitt. His father was a noted art historian and his grandfather, Louis, a celebrated landscape painter.

During World War I, Hildebrand served with distinction as an infantry officer and was wounded three times. After the war, he was finally able to study the history of art in his home town of Dresden and soon gained his doctorate.

In 1925, aged just 30, Hildebrand was appointed director of the city art gallery in Zwickau, 50 miles south of Leipzig. There, he quickly established a stellar reputation for promoting the works of modern artists such as Paul Klee.

However, in 1930, according to what he would later claim in his interrogation by the Americans, his taste for ‘degenerate’ modern art and his Jewish ancestry ‘incurred the enmity of the Nazis’ and he was dismissed from his post.