Mark Tapson

Huffington Post

October 25, 2013

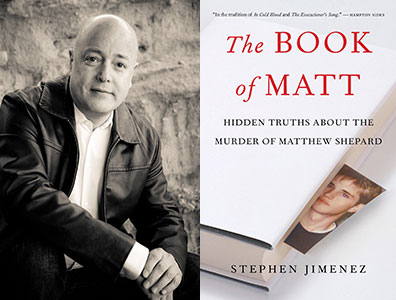

Almost exactly fifteen years ago, Matthew Shepard, 21, a gay college student, was horrifically beaten by two presumed anti-gay bigots and left for dead, tied to a fence on the outskirts of Laramie, Wyoming. Overnight, Shepard became a martyred icon of homophobic violence and a propulsive force for the enactment of hate crime legislation. Everyone knows, or thinks they know, these broad strokes of the terrible tale – but self-described “gay, liberal” journalist Stephen Jimenez says that what everyone knows isn’t the whole story.

Upon hearing of Shepard’s fate, two friends immediately contacted a gay reporter and local gay organizations, and the national media ran with it from there. “Once it started,” said prosecutor Cal Rerucha, “it took off like wildfire,” though he later acknowledged to Jimenez that “I don’t think the proof [of a hate crime] was there.” The news media quickly fell into a uniform account of the crime and the motive behind it.

The perpetrators Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson (purportedly strangers to Shepard) were ultimately convicted of kidnapping, aggravated robbery, and second-degree murder – but not of a hate crime, which was not on the books in Wyoming at the time. Nonetheless, Shepard’s death brought national and international attention and sympathy to the issue of hate crimes, and the Matthew Shepard Act, which President Obama signed into law in 2009, became the wedge pushing an expansion of legislation dealing with crimes against victims for their gender or sexual orientation. Shepard’s story has since been engraved in the public consciousness in songs, plays, movies, documentaries, and books.

Now comes The Book of Matt: Hidden Truths About the Murder of Matthew Shepard, in which Jimenez details his thirteen-year investigation that covered twenty states and more than a hundred interviews, and in which he had privileged access to previously unavailable documents and information. He initially went to Laramie in 2000 to research the story of the murder, after McKinney and Henderson were sentenced to life without parole. His aim was to write a screenplay to dramatize what he, like the rest of the nation, believed to be a clearcut incident of vicious bigotry. But what Jimenez gradually uncovered in that “tight-knit, somewhat incestuous” town was layer upon layer of ugly secrets and potentially myth-busting revelations about the relationship between Shepard and his killers, and their involvement in the deadly underworld of methamphetamine trafficking.

From the beginning, Jimenez met with resistance about pursuing his politically sensitive angle of the story. The familiar argument he heard was, “let slumbering truths lie when so much good has been accomplished in Matthew’s name.” Shepard was the Emmett Till of gay rights, he was told. But Jimenez felt that “clinging to a partly false mythology could never yield the subtler, more powerful meanings of his sacrifice,” and it “would be a disservice to Matthew’s memory to freeze him in time as a symbol, having stripped away his complexities and frailties as a human being.”

Jimenez had actually co-produced a controversial 2004 20/20 segment on the murder which, like the new book, challenged “the widely accepted scenario of an innocent gay man targeted for robbery and murder by two homophobic strangers because he made a pass at them.” But even the network refused to air certain revelations it deemed too “editorially explosive” – revelations that not only was Aaron McKinney not unknown to Shepard, but that he was a bisexual hustler who had partied on numerous occasions with Shepard and actually had sex with him in exchange for drugs and money.