Adam Mann

Wired

October 11, 2013

Tell your film buff friends they’re right: the most creative period in cinema history was probably the 1960s. At least that’s the takeaway from a detailed data analysis of novel and unique elements in movies throughout much of the 20th century.

How do you objectively measure creativity in movies? Though there’s probably no perfect way, the recent research mined keywords generated by users of the website the Internet Movie Database (IMDb), which contains descriptions of more than 2 million films. When summarizing plots, people on the site are prompted to use keywords that have been used to describe previous movies, yielding tags that characterize particular genres (cult-film), locations (manhattan-new-york), or story elements (tied-to-a-chair).

Each keyword was given a score based on its rarity when compared to previous work. If some particular plot point – like, say, beautiful-woman – had appeared in many movies that preceded a particular film, it was given a low novelty value. But a new element – perhaps martial-arts, which appeared infrequently in films before the ’60s – was given a high novelty score when it first showed up. The scores ranged from zero to one, with the least novel being zero. Lining up the scores chronologically showed the evolution of film culture and plots over time. The results appeared Sept. 26 in Nature Scientific Reports.

The researcher behind the findings, physicist Sameet Sreenivasan of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, was at first somewhat surprised at some of his results.

“You always hear about how the period from 1929 to 1950 was known as the Golden Age of Hollywood,” he said. “There were big movies with big movie stars. But if you look at novelty at that time, you see a downward trend.”

This result is likely familiar to any student of film history, who knows that this golden age also corresponded to a time when nearly all movies were produced and released by a handful of studios. The Big Five in particular reigned supreme through the practice of block booking. Studios produced several A-movies with big stars and high production values. But local theatres, which were monopolistically owned by the Big Five, were forced to also show the studio’s B-movies, often starring rising or fading actors and featuring formulaic plot lines.

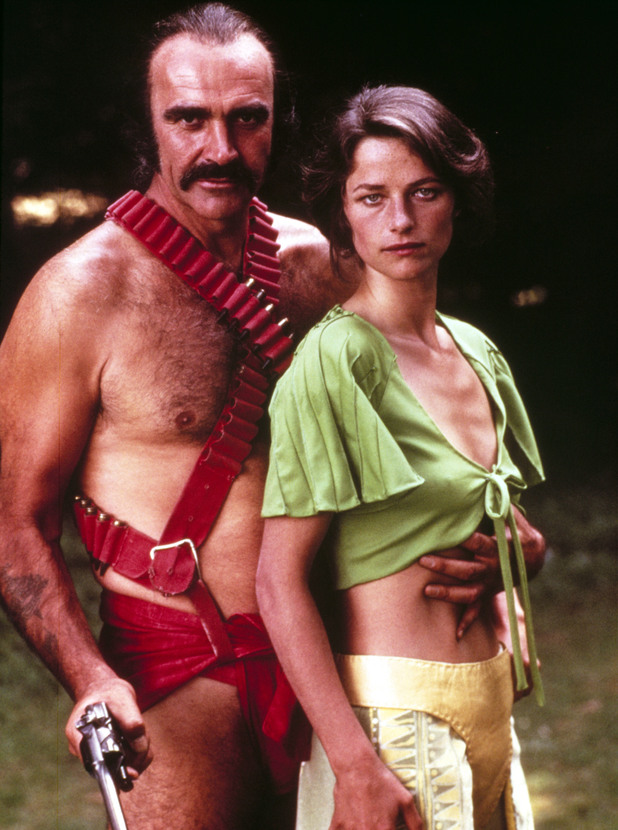

When the studio system crumbled in the mid-50s, there was a burst of creativity. Audiences were introduced to independent films of the American New Wave genre — such as Bonnie and Clyde, released in 1967 — as well as European art house, French New Wave, spaghetti westerns, and Japanese cinema. The novel styles, plot lines, and film techniques create a noticeable uptick in Sreenivasan’s analysis.

Unsurprisingly, the research also suggests that unfamiliar combinations of themes or plots that haven’t been encountered before (something like sci-fi-western) often have the highest novelty scores.