Stuff Black People Don’t Like

August 22, 2014

- In 1970, Ferguson was 99 percent white [5 things to know about Ferguson Police Department, USA Today, 8-19-2014]

- In 1980, Ferguson was 85 percent white and 14 black [The Death of Michael Brown: Racial History Behind the Ferguson Protests, New York Times, 8-12-14]

- In 1990, Ferguson was 73.8 percent white and 25.1 percent black

- In 2000, Ferguson was 44.8 percent white and 52.4 percent black

- In 2010 Ferguson was 29.3 percent white and 67.4 percent black [Chart: Inside Ferguson’s Changing Demographics, Forbes, 8-19-2014]

More to the point, the racial transformation of Ferguson isn’t unique to the city of St. Louis and its surrounding suburbs. Once restrictive covenants (freedom of association) was declared unconstitutional in 1948 by the Supreme Court, the last line of defense for maintaining the integrity of white communities was gone.

St. Louis Metromorphosis: Past Trends and Future Directions (edited by Brady Baybeck and F. Terrence Jones), published in 2004 by the Missouri Historical Society Press, offers illuminating reading into the vast history of the black undertow overwhelmingly formerly all-white communities in the St. Louis metro-area, and gives us this information on the “racial tipping point” (once a municipality passes 30 percent African American, it accelerates toward becoming overwhelmingly black):

In 1960, the St. Louis region had yet to begin dismantling much of the legal segregation affecting housing patterns. Although restrictive covenants had been declared unconstitutional in 1948, the legacy of past segregation continued, and more affirmative fair housing legislation banning private discrimination would not be passed until later in the 1960s. It is not surprising that 84 percent of the municipalities were predominantly white (i.e., less than five percent black) and only 6 percent were more than one-fifth African America, with one-third of these being two historically all-black communities: Brooklyn and Kinloch.

From 1970 forward, however, many municipalities have experienced substantial racial transition… at least since 1980, whites are unlikely to avoid areas or flee them when the African American share exceeds 5 percent but remains under one-fifth. They do, however, become increasingly nervous as the proportion goes past one-fifth and toward one-half. Shifting to political power, both because they are on average young and because their political participation rates are lower, blacks have some but less than proportional control when their share exceeds a majority but is less than about two-thirds. African American then typically achieve political control above 65 percent and, once the community exceeds 95 percent, it is essentially as single race as the 95 percent+ white cities.

Between 1960 and 2000, over half the cities developed at least a visible (i.e., 5 percent or higher) black population and only a minority – although a substantial one at 42 percent – remain predominantly white. For some municipalities, the transition from white to black was rapid. Each decade witnessed cities having their African American share increase 30 percentage point or more, indicating that racial tipping – a dramatic shift from white to black – has not gone out of style. Here are some example: for 1960 to 1970, Alorton (18 percent to 80 percent black) and Wellston (8 percent to 69 percent black); for 1970 to 1980, Berkeley (9 percent to 49 percent), Pagedale (23 percent to 79 percent), Pine Lawn (29 percent to 81 percent), and Washington Park (0 percent to 49 percent); for 1980 to 1990, Bel Ridge (25 percent to 61 percent) and Moline Acres (32 percent to 64 percent); for 1990 to 2000, Dellwood (9 percent to 58 percent), Jennings (48 percent to 78 percent), and Cahokia (5 percent to 38 percent). Over forty years, eighteen cities went from less than 1 percent black to more than 65 percent African American: Bel Ridge, Berkely, Cool Valley, Country Club Hills, Flordell Hills, Greendale, Hanley Hills, Hillsdale, Jennings, Moline Acres, Normandy, Northwoods, Pagedale, Pasadena Hills, Pine Lawn, Velda City, Velda Village Hills, and Washington Park.

Is racial tipping inevitable? Once the black share began to increase, has any city been able to stabilize at some equilibrium short of two-thirds or more black? Yes, but the numbers are few. Only two have gone past 30 percent black and not passed 60 percent black within two decades: the City of St. Louis, which went from 29 percent black in 1060 to 41 percent in 1970 but now is just ten points higher (51 percent) in 2000, and University City, which leapt from 0 percent black to 43 percent between 1960 and 1980 but has stayed much the same (45 percent in 2000) since then.

Even during the past two decades when there has been heightened awareness about the social costs of residential segregation and the negative consequences of rapid racial transition and awareness of recent examples such as University City about what policies might achieve a stable racial mix, the prevailing pattern has been: once a municipality passes 30 percent African American, it accelerates toward becoming overwhelmingly black. (p. 287 – 289)

Which brings us back to 1948, when Shelley vs. Kraemer was decided in the Supreme Court and restrictive covenants were declared unconstitutional.

Just who is the Shelley? Hilariously, the surname Shelley belongs to a black man who wanted to live in a white community in St. Louis… [Shelley House: Historic Places of the Civil Rights Movement, National Park Services (NPS.gov)]:

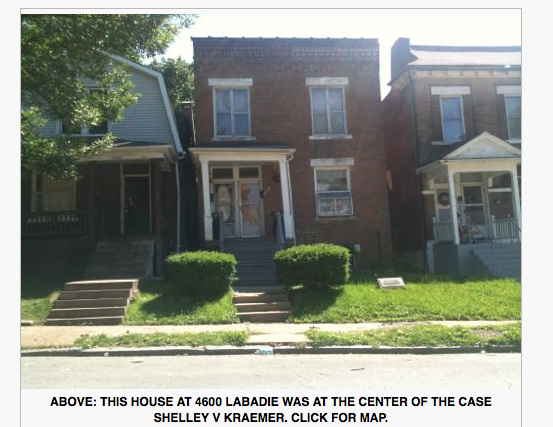

This modest, two-story masonry residence built in St. Louis, Missouri in 1906 is associated with an African American family’s struggle for justice that had a profound effect on American society. Because the J. D. Shelley family decided to fight for the right to live in the home of their choosing, the United States Supreme Court addressed the issue of restrictive racial covenants in housing in the landmark 1948 case of Shelley v. Kraemer.

In 1930, J. D. Shelley, his wife, and their six children migrated to St. Louis from Mississippi to escape the pervasive racial oppression of the South. For a number of years they lived with relatives and then in rental properties. In looking to buy a home, they found that many buildings in St. Louis were covered by racially restrictive covenants by which the building owners agreed not to sell to anyone other than a Caucasian. The Shelleys directly challenged this discriminatory practice by purchasing such a building at 4600 Labadie Avenue from an owner who agreed not to enforce the racial covenant. Louis D. Kraemer, owner of another property on Labadie covered by restrictive covenants, sued in the St. Louis Circuit (State) Court to enforce the restrictive covenant and prevent the Shelleys from acquiring title to the building. The trial court ruled in the Shelleys’ favor in November of 1945, but when Kraemer appealed, the Missouri Supreme Court, on December 9, 1946, reversed the trial court’s decision and ordered that the racial covenant be enforced. The Shelleys then appealed to the United States Supreme Court.

On May 3, 1948, the United States Supreme Court rendered its landmark decision in Shelley v. Kraemer, holding, by a vote of 6 to 0 (with three judges not sitting), that racially restrictive covenants cannot be enforced by courts since this would constitute state action denying due process of law in violation of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. Although the case did not outlaw covenants (only a state’s enforcement of the practice), in Shelley v. Kraemer the Supreme Court reinforced strongly the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection of the laws, which includes rights to acquire, enjoy, own, and dispose of property. The Shelley case was a heartening signal for African Americans that positive social change could be achieved through law and the courts.

The Shelley House, a National Historic Landmark, is located at 4600 Labadie Avenue in St. Louis, Missouri. The house is a private residence and is not open to the public.

The ruin of an entire metro region (St. Louis) has occurred: not by asteroid, nuclear strike, famine, earthquake, or an invading foreign army, but by the unleashing of blacks via declaring restrictive covenants unconstitutional.

Just look at how quickly communities have collapsed to the emergence of the black undertow (the racial tipping point is 30 percent, then the community goes black fast)…

But what of the Shelley House, a National Historic Landmark, in 2014?

Oh, it’s a fitting tribute to the Civil Rights movement.

You can consult Google StreetView for a taste of racial realities only a God who doesn’t play dice would see fit to ensure exists via the Visible Black Hand of Economics.

As late as 2011, a house (which had been there since the 1920s) was located to the left of the National Historic Landmark “Shelley House,” but it has since been razed..

So here’s what we know:

- Ferguson went from 99 percent white in 1970 to 27 percent white today

- Not just Ferguson, but scores of St. Louis metro-communities went from almost entirely white to majority black, with the ability for the white residents to practice freedom of association (restrictive covenants) declared unconstitutional

- The National Historic Landmark “Shelley House” is a silent witness to the black undertow effect, a reminder the Visible Black Hand of Economics is far more devastating long term weapon than any weapon currently in the United States Military arsenal

Remember: God might not play dice, but he has a great sense of humor… just look at the state of the Shelley House in 2014.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History