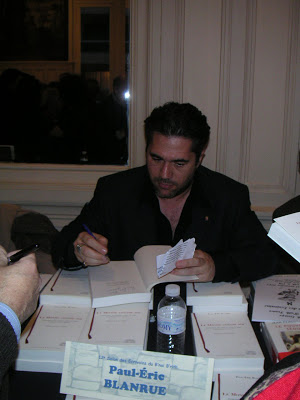

Guillaume Durocher

Occidental Observer

September 25, 2015

Paul-Éric Blanrue is a French writer whose most recent books have documented Jewish power networks in France, especially their relationship with the center-right under Nicolas Sarkozy and with the “far-right” Front National under the Le Pen family.[1] The thesis of these books, meticulously documented, is that Jewish influence in elite French political and cultural circles is enormous. Blanrue quotes countless French political leaders and commentators remarking upon this, but also shows how, if any are critical, they are swiftly punished.

Elite political and cultural power in France is thus distorted by Jewish perceived interests and ethnic biases, to the detriment of non-Jewish groups. The native French suffer demonization at the hands of a holocaust-centric memorial culture, the de facto exclusion of French nationalists from normal democratic politics, and the de jure censorship of indigenous European advocates, race-realists, and revisionists. Arabs and Muslims also suffer at home with a noxious combination of continued immigration and race-baiting, and abroad since at least 2007 with unconditional French support for Israel and the American Empire against the Palestinians, Libyans, and Syrians.

The story of Blanrue’s career, of his evolving relationship with the organized Jewish community, and of his difficulties publishing books on Jews is itself ironic and instructive. In 2007, he sought to publish a dictionary of anti-Semitism, with over 500 Judeo-critical statements that have been made throughout history by prominent leaders and intellectuals, entitled Le Monde contre soi (The World Against Oneself). The mainstream publisher Grasset declined to accept the book, deeming it “impossible to publish.” Grasset’s editorial chief, Jean-Paul Enthoven, wrote Blanrue in April of that year:

Dear Paul-Éric Blanrue,

I have then examined very closely, and with great interest, this Dictionary of Anti-Semitism. This is a considerable and useful work, loaded with information – but [is], in my opinion, impossible to publish. . . .

Yours, with great sympathy.

PS: Yann Moix [a journalist], who shows a venerable and faultless friendship for you, told me he would accept to preface your book. Supposing that it could one day be published, believe me when I say that I will advise him with all my strength to not fulfill such a friendly duty. This would add a useless magnetic cloud to his reputation (such as some of his enemies would like to fix it) and would complicate the release of his next novel – and neither you, nor I, can want this to happen.[2]

Thus a major publisher believed that mere association with a work documenting the history of anti-Semitism would be deeply damaging to a writer’s career and lead to informal censorship of his work.

Le Monde contre soi was later published by Les Éditions Blanche,[3] a less prestigious publishing house mainly dealing with erotic literature, which for this reason appears to benefit from an unusual degree of intellectual freedom (Blanche is also the publisher of French nationalist and anti-Judaic activist Alain Soral; see my 3-part series on Soral).

Ironically, apparently contrary to Grasset’s fears, this dictionary of anti-Semitism proved a hit with the organized Jewish community. Indeed, Blanrue was invited by the B’nai B’rith of France (the racially-exclusive Jews-only Masonic group) to present Le Monde contre soi at their November 2007 book fair. The book indeed still features prominently in the Paris Shoah Memorial museum’s online bookstore.[4] Jewish leaders evidently thought the book served to “educate” non-Jews about the terrible hostility towards Jewish culture manifested in all times and places.

The book was republished in 2012 by Soral’s publishing house Kontre Kulture. This time however Jewish groups would have none of it, and the International League Against Racism and Anti-Semitism (LICRA, on which see my “The Culture of Critique in France: A review of Anne Kling’s books on Jewish influence”) sued to censor the dictionary and four historical works on Jewry (Édouard Drumont’s La France juive, Léon Bloy’s Le Salut par les juifs, and French translations of Henry Ford’s The International Jew and Douglas Reed’s The Controversy of Zion) on grounds of “incitement of racial hatred.” Incidentally the “anti-racist” LICRA and the no-gentiles-allowed B’nai B’rith are close organizations, having shared the same president for many years.

As ever, the question of whether the work was to be promoted or suppressed was not its truth or its value as a historical document, but narrow tribal interests. The B’nai B’rith had promoted the book thinking it would stoke sympathy for Jews. The LICRA suppressed the book when it realized that such a dictionary might lead people to ask: Wait, just why has this culture attracted such consistent and acute criticism throughout the world and throughout the ages from so many of history’s greatest political leaders and intellectual geniuses? The LICRA intuitively sensed that Jewish power and privilege could surely not survive such scrutiny. As of today, the four historical works remain censored while an appellate court re-legalized Blanrue’s dictionary last February.[5]

Early in Sarkozy’s term as president and inspired by John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt’s The Israel Lobby,[6] Blanrue decided to write a similar study on France. This became Sarkozy, Israël et les Juifs, a very measured and moderate book. In particular, Blanrue shows that the quarter-Jewish Sarkozy was both raised in a culturally Jewish social milieu (by his Jewish grandfather) and rose politically in such a milieu, namely as mayor of the wealthy town of Neuilly (carefully cultivating the local community’s wealthy Jews and rabbinate). He presents Sarkozy’s election as President of the Republic as a kind of replacement of vestigial Gaullist French elites, which had some concerns for independence from the United States and a balanced policy towards Israel, by significantly-Jewish neoconservative ones.

Sarkozy – now in opposition and seeking to re-election to the presidency – has made a number of shockingly Judeo-centric statements since Blanrue’s book was published, probably because he swims in these milieux and, no doubt, to pander to Jewish oligarchs. On November 25, 2014, Sarkozy told a French audience: “I will never accept that Israel’s right to security be questioned. Never. It is the struggle of my life!”[7] On June 8, 2015, he told an Israeli audience: “[the Shoah] remains an indelible stain in the consciences of humanity, and we have all contracted towards the Jewish people a debt which cannot be extinguished.”[8] As Russell Kirk might have said: Is Sarkozy running for the Élysée Palace or for the Israeli Knesset?! And yet this man was and aspires to again be the Chief of State of France! These Judeo-centric and Israelo-centric comments – and let me recall that 99 percent of the French population is made up of non-Jews – have attracted no criticism in mainstream media. Do not an admission that Israel is first in his heart (“the struggle of my life”) and an apparent reduction of humanity to eternal debt slavery (“a debt which cannot be extinguished”) make him ineligible to be President of the French Republic?

In any event, Blanrue found it very difficult to publish Sarkozy in 2009, despite the work being very cautious in its language. Even Franck Spengler, no stranger to controversy as the head of Éditions Blanche, declined to publish Sarkozy. He wrote Blanrue:

As for publication, alas the answer is no, for in addition to the risks, though moderate, of releasing this book, we will not get one line in the press and still less on television and radio, precisely because of the control of those whom we cannot name and their lackeys. And it isn’t a little splash on the Internet that will sell the book in stores. The book would not be not banned, to be sure, but the book would be given the silent treatment and have even less sales than Le Monde contre soi which, alas, did not have the success it deserved due to the silence that surrounded it.[9]

The book ended up having to be released by an obscure publisher outside of France – Belgium’s Oser Dire – and then faced difficulties even to find a distributor to enter French bookstores, requiring four months to do so. In June 2009, Blanrue hosted a press conference in Paris to promote the book. The event attracted a room-full of attendees, but only two journalists: an independent Englishwoman and Marc de Miramon of the Communist L’Humanité. Shortly after the Parisian bookstore Résistances, which had placed Sarkozy in the window display, was ransacked by thugs from the Jewish Defense League – an extremist ethnic militia banned in Israel and the United States, but which enjoys free rein in France – its computers and books destroyed, the latter by drenching them in oil. Again, there was virtually no media coverage of this equivalent of book-burning.[10]

Blanrue’s book then faced a media blackout, only being reviewed in the Tunisian, Egyptian, and Saudi media (which, I am forced to observe, testifies to the undeniably far greater degree of free speech on Jewish issues in non-Western countries generally).

One might think the book’s somewhat provocative title – which refers to an old work by the famou s Jewish liberal-conservative thinker Raymond Aron[11] – might be the problem which led to the omertà. But Blanrue notes that mainstream French media had used article titles like “Obama, Israel, and the Jews” and favorably reviewed a pro-Israel book by former Israeli Ambassador to France Freddy Aytan with a suspiciously similar title.[12] The issue was not the title but rather that Blanrue’s book was critical in documenting Sarkozy’s pandering to strongly-identified, ethnocentric Jews, the prominence of many of these Jews in his government, and that this ethnic bias accounted for a sharply pro-Israeli shift in French foreign policy, to the detriment of both Palestinian rights and objective French interests.

Blanrue writes:

I am facing a de facto censorship and not an official prohibition. The method is all the more insidious: The brutal banning of my book by a ministerial order, or on the suggestion of an ethnic organization, would perhaps have provoked tens of thousands of indignant reactions, and at a minimum would have signaled my existence. . . . Some journalists were afraid . . . . Never has the Israeli question been so taboo; never has the French Republic been so closely bound up with a network dedicated to the Zionist cause.[13]

Blanrue was supported by a number of personalities[14] who had the intellectual honesty to submit Jewish racism and Israeli colonialism to the same critique that is typically reserved for Whites. Alain Gresh, of the far-left Le Monde diplomatique magazine, wrote: “This books deserves a debate, not a de facto ban.”

This however proved completely insufficient to break the wider omertà and in Blanrue’s next book, Jean-Marie, Marine et les Juifs, the writing is franker and more biting. Evidently no longer believing intellectual freedom is possible in France, Blanrue has since expatriated himself, first moving to Belgium and then to Venice, where he now lives. However, his works have enjoyed considerable visibility in French alternative media. As ever, freedom of thought on this question only exists online.

Incidentally, the novelist Yann Moix, who had been so supportive of publishing Blanrue’s dictionary of anti-Semitism and even prefaced the work, has since become a talking head on the public TV channel France 2. Moix, who had also opposed legal censorship on the Holocaust, has apparently got burned and is now terrified of association with politically-incorrect figures like Blanrue. This is the carrot and stick at work. When recently asked at a book fair about his preface to Blanrue’s book, Moix could think of no better answer than to flee the scene.[15] Human beings, being human, will typically respond to incentives, and the war on Whites and their culture is nothing if not incentivized . . .

[1]Paul-Éric Blanrue, Sarkozy, Israël et les Juifs (Embourg, Belgium: Éditions Oser Dire, October 2009, third edition) and Jean-Marie, Marine et les Juifs (Embourg, Belgium: Éditions Oser Dire, 2014).

[2]Blanrue, Sarkozy, 6.

[3]Paul-Éric Blanrue, Le Monde contre soi: Anthologie des propos contre les juifs, le judaïsme et le sionisme (Éditions Blanche, 2007).

[4]http://librairie.memorialdelashoah.org/ficheproduit.asp?pid=17D7891C&rid=5F5E101&uid=131221183757719661892

[5]“Anthologie des propos contre les juifs, le judaïsme et le sionisme à nouveau disponible sur Kontre Kulture !,” Égalité et Réconciliation, February 17, 2015. http://www.egaliteetreconciliation.fr/Anthologie-des-propos-contre-les-juifs-le-judaisme-et-le-sionisme-a-nouveau-disponible-chez-Kontre-29636.html

[6]John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt, The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux), 2007. Reviewed in Kevin B. MacDonald, “The Israel Lobby: A Case of Jewish Influence,” The Occidental Observer, 7(3), Fall 2007, 33-58. http://kevinmacdonald.net/M&WReview.pdf

[7]“Rappel : ‘La sécurité d’Israël est le combat de ma vie,’” Égalité et Réconciliation, May 31, 2015. http://www.egaliteetreconciliation.fr/Rappel-Sarkozy-La-securite-d-Israel-est-le-combat-de-ma-vie-33208.html

[8]“Sarkozy condamne l’humanité au tapin éternel,” Égalité et Réconciliation, June 12, 2015. http://www.egaliteetreconciliation.fr/Sarkozy-condamne-l-humanite-au-tapin-eternel-33434.html

[9] Blanrue, Sarkozy, 6.

[10]Diana Johnstone, “Zionist Fanatics Practice Serial Vandalism in Paris,” Counterpunch, July 6, 2009. http://www.counterpunch.org/2009/07/06/zionist-fanatics-practice-serial-vandalism-in-paris/

[11]De Gaulle, Israël et les juifs, which I discuss in Guillaume Durocher, “The Jew as Citizen: Raymond Aron & Civic Nationalism,” North American New Right, November 5, 2014. http://www.counter-currents.com/2014/11/the-jew-as-citizen-part-1/

[12]Freddy Eytan, Sarkozy, le monde juif et Israël (Éditions Alphée, 2009).

[13]Blanrue, Sarkozy, 195-6.

[14]Including the anti-Zionist Belgian university professor Jean Bricmont, the former university professor and United Nations/European Union adviser Roger Briottet, and film director Frank Barat.