Jacob Aron

New Scientist

July 10, 2013

Alan Turing and an army of codebreakers took years to crack the Enigma code during the second world war. Just be thankful the Nazis weren’t using a quantum Enigma machine.

Quantum key distribution (QKD) can already keep secret the key to a code. “I was trying to think of alternatives,” says Seth Lloyd at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “It occurred to me that it would be interesting to quantise the Enigma machine.”

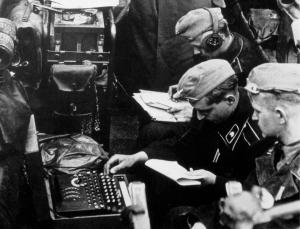

Enigma machines are like souped-up typewriters, with an illuminated panel above the keyboard that also displays the alphabet. Type in a letter and a different letter on the panel lights up, indicating how to encrypt that character.

Wired rotors do the scrambling by guiding an electrical signal along a certain path. Crucially, with each new letter, the path changes, so if you type the same letter again it will be encrypted differently – avoiding the repeated letter patterns that codebreakers rely on. The change isn’t random, but depends on the initial rotor settings, which work as the key.

If you know the settings – Enigma operators had books specifying them – the encrypted words can be typed into another Enigma machine to reveal the message.

Turing and his colleagues relied on external information, such as knowledge that a message was likely to be about the weather, to make educated guesses at its content, which often led them to the key. In other words, they turned an increase in information about the message into a reduction in the key’s strength.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History