Henry Wolff

AmRen

November 3, 2013

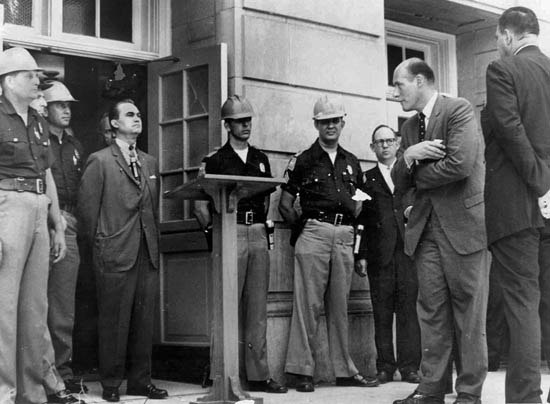

Fifty years ago at the University of Alabama, Governor George Wallace made a stand for the right of public institutions to discriminate by race, but the federal government persuaded him that there would be no segregation tomorrow, much less forever.

In September, hundreds of UA students evoked that legacy when they marched behind a banner reading “The Final Stand in the Schoolhouse Door.” They were protesting what they consider the last form of formal segregation on campus—and perhaps in society—the university’s fraternity system. To be more accurate, they weren’t protesting the eight traditionally black sororities and fraternities, which haven’t accepted a white member since 2007; they were opposing the membership practices of the predominately white Greek organizations.

Controversy began when two black girls who rushed the traditionally white sororities did not receive membership offers from any of the 16 on campus–none of which had a single black member. The university newspaper The Crimson White used mostly anonymous sources—only one gave her name—to paint a grim portrait of white sorority members clamoring for diversity but stymied by socially backward alumnae or, in one case, an adviser. National media picked up the story, leading Gov. Robert Bentley—a UA alumnus—to say that sororities should choose members based on proper qualifications, not race.

Controversy began when two black girls who rushed the traditionally white sororities did not receive membership offers from any of the 16 on campus–none of which had a single black member. The university newspaper The Crimson White used mostly anonymous sources—only one gave her name—to paint a grim portrait of white sorority members clamoring for diversity but stymied by socially backward alumnae or, in one case, an adviser. National media picked up the story, leading Gov. Robert Bentley—a UA alumnus—to say that sororities should choose members based on proper qualifications, not race.

Jesse Jackson came to the campus and suggested students browbeat the white sororities until they give in. “Gender or racial segregation is abhorrent to an intelligent, civilized people,” he told The Crimson White. “What’s at stake here is your future, not the traditions of their past.”

As pressure mounted, UA President Judy Bonner met with sorority advisers and decided to let the sororities increase the number of their members and establish open bidding—girls who never went through rush could be offered membership at any time—so that sororities could add non-whites before the next year.

The pressure was effective. A little more than a week after the first student newspaper report, Dr. Bonner released a video announcing “progress”: 14 non-white women, including 11 blacks, were offered membership; four blacks and two other non-whites accepted.

The Crimson White editorial board declared that “History has been made.” A Salon headline was “Finally! Alabama ends segregated sororities after public shaming.” Most reports read as though a “color barrier” had been broken, even though the “Jackie Robinson” of Alabama sororities pledged back in 2003.

The reality, of course, is that the Alabama Greek scene will remain mostly segregated, just as it is on campuses everywhere. Whites and blacks socialize separately, and few students of either race want to be tokens in organizations held together by racially-rooted traditions. Alabama’s white sororities will let in a few white-acting non-whites each year to fend off charges of “racism,” but they will remain largely unchanged.

Why the outrage?

The real significance is symbolic. Diversity-mongers get nervous whenever organizations or even hobbies are largely white (see these recent articles about CrossFit and marathons). Tokenism is an important step in dissolving racial, cultural and social exclusiveness. It leads to the assumption that since some non-whites can act white, race is only skin-deep and not part of group identity.

Greek organizations are some of the few remaining bastions of white identity—and they have deep roots. Their beginnings go back to the founding of the republic, and some of today’s most popular fraternities and sororities were formed just after the Civil War. These groups are bound by longstanding traditions and a multigenerational alumni base that includes some of the most prominent members of American society.

Last year, about 950 colleges and universities reported Greek participation to U.S. News. Particularly in the South, where fraternities are an important part of culture on campus and beyond, it’s not uncommon for a fifth or more of a school’s students to “go Greek.” Unspoken racial segregation is the norm for Greeks nationwide, though there are no reliable demographic data.

Traditionally-white Greek houses are informally sorted into “tiers.” Members of top-tier houses typically come from well-to-do families, have social graces, are some of the best looking and best dressed students on campus, tend to have the best Greek houses, and are overwhelmingly white. Top-tier fraternities have the most rigorous hazing, and top-tier sororities demand strict behavior of their members. When anti-Greek academics rage about “privilege,” they’re probably thinking of top-tier houses.

Bottom-tier Greeks enjoy less “privilege,” and their members are sometimes indistinguishable from the general student body. They are still mostly white, though they usually accept a few non-whites.

Bottom-tier Greeks enjoy less “privilege,” and their members are sometimes indistinguishable from the general student body. They are still mostly white, though they usually accept a few non-whites.

These informal rankings within already selective systems make Greek life one of the more exclusive institutions in America. This, combined with the prominence of many of their alumni, makes them ideal targets for opponents of hierarchy. Many people would like to change these groups fundamentally or do away with them completely.

These informal rankings within already selective systems make Greek life one of the more exclusive institutions in America. This, combined with the prominence of many of their alumni, makes them ideal targets for opponents of hierarchy. Many people would like to change these groups fundamentally or do away with them completely.

Modern Persians

University administrators typically undermine tradition. In her video statement announcing the admission of non-whites to UA sororities, President Bonner said “I am confident that we will achieve our objective of a Greek system that is inclusive, accessible and welcoming to students of all races and ethnicities. We will not tolerate anything less.”

To achieve their goals, administrators can impose any number of penalties: social probation, curtailing pledge periods, or banning a chapter outright. Arizona State recently pushed fraternity housing off campus, and some schools have banned all Greeks.

Such anti-Greek actions are done for legal cover and to give the impression of effective administration in the face of negative publicity, but most administrations probably oppose the very idea of exclusive organizations. Occasionally, they are honest about this.

At Princeton, 15 percent of students belong to Greek organizations, which are not officially recognized by the university. In 2011, Princeton President Shirley Tilghman–a Canadian–announced a ban on freshmen participation. As she explained:

. . . Princeton’s Greek-letter organizations are significantly less heterogeneous than our student body as a whole, recruiting a disproportionate number of white, affluent, and privately educated members and serving as a pipeline to selective eating clubs. . . . The kind of social and economic stratification that this engenders undermines a cardinal goal of a Princeton education: to introduce students to as wide a span of perspectives and experiences as possible. In our globalized and multicultural society, comprehension of and affinity with those least like ourselves have never been more important, especially in freshman year, when foundational friendships are formed.

There are also some non-Greek students (God Damn Independents, or GDIs, as some Greeks call them) who oppose fraternities. VICE recently profiled a long-lived group at UA called the Mallet Assembly which led the sorority protests. The assembly “celebrates equality and diversity,” and a glance at its members suggests why.

Similar students typically staff school newspapers—which are regularly accused of anti-Greek bias—and graduate to fill the ranks of the major media, where they will write ominously about the latest hazing scandal or Mexican-themed parties where Greeks wore sombreros.

Sometimes, the impetus for “inclusion” comes from a Greek organization’s “nationals”—the parenting group that has the authority to revoke the charters of individual chapters.

The Kappa Alpha Order (KA) was founded in 1865 at Washington and Lee University and spread throughout the South. In 1923, Robert E. Lee was declared the “spiritual founder” of the group, and the organization remains steeped in Southern tradition. In 2010, however, KA nationals banned Confederate uniforms at the traditional “Old South” parties and parades, where men dressed as soldiers and women wore hoop dresses. The ban came after a black UA sorority complained that the Confederate procession had paused in front of its house on campus.

Greek national organizations want more members and no bad publicity, and so are willing to water down traditions and make concessions that will keep them in the good graces of university administrators. They sponsor and support week-long programs for chapter leaders such as LeaderShape and the Undergraduate Interfraternity Institute that teach squishy things like “inclusive leadership” and encourage students to make “bold change” and to confront “the harsh realities of the current state of fraternity/sorority life.”

Greek national organizations want more members and no bad publicity, and so are willing to water down traditions and make concessions that will keep them in the good graces of university administrators. They sponsor and support week-long programs for chapter leaders such as LeaderShape and the Undergraduate Interfraternity Institute that teach squishy things like “inclusive leadership” and encourage students to make “bold change” and to confront “the harsh realities of the current state of fraternity/sorority life.”

Going “forward”

The future for fraternities looks grim. Greek students, who are rarely on campus for more than four years, are up against entrenched administrations and hostile media. Forty-four states have passed anti-hazing laws that criminalize even benign initiation rites under the guise of preventing acts which were already illegal.

Federal authorities investigate the slightest whiff of “discrimination,” as well as any claim that Greeks have created a “hostile environment” for women or minorities. They threaten to withhold federal university funding in order to pressure administrations.

The most popular fraternity website, Total Frat Move, has voiced its support for “anti-discrimination.” A few holdouts, such as the popular forum Old Row, will value tradition over conformity, but in the long run, if traditional Greek organizations want to maintain their character they will probably need to go off campus and underground.