Daily Mail

July 19, 2013

Relations between Russia and Germany have not been good since Vladimir Putin’s nationalist sabre-rattling this summer, but they are about to get a whole lot worse.

A new film about to be released in Germany will force both countries to re-examine part of their recent history that each would much prefer to forget. Yet it is right that the ghastly truth should finally be acknowledged.

The movie, A Woman In Berlin, is based on the diary of the German journalist Marta Hillers and depicts the horror of the Red Army’s capture of the capital of the Third Reich in April and May 1945.

Marta was one of two million German women who were raped by soldiers of the Red Army – in her case, as in so many others, several times over.

It was a feature of Russia’s ‘liberation’ and occupation of eastern Germany at the end of World War II that is familiar enough to historians, but which neither country cares to acknowledge took place on anything like the scale it did.

For Russia, the episode besmirches the fine name of the Red Army that had fought so hard and suffered so much in its four-year campaign against the Wehrmacht.

The courage and resilience of the ordinary Russian in what they called the Great Patriotic War is incontestable, and for every five German soldiers killed in action in the whole of World War II, four died on the Eastern Front.

Yet the knowledge that the victorious Red Army committed mass rape across Prussia and eastern Germany as they closed in on Berlin degrades its reputation, which is unacceptable to many Russians today.

When the historian Antony Beevor wrote about it in his book Berlin: The Downfall, the Russian ambassador to London, Grigory Karasin, accused him of ‘an act of blasphemy’, saying: ‘It is a slander against the people who saved the world from Nazism.’

Similarly, living Germans do not want the events that humiliated and violated them, their mothers and grandmothers to be held up to public examination, as this movie promises to do.

For many German women, the memory was something they sublimated and never spoke about to their husbands returning from the front.

It was the great unmentionable fact of 1945, which is coming out not just in history books, but in front of a mass, international audience. Painful memories of gross sexual abuse are being dragged out and held up to the pitiless witness of the silver screen.

Furthermore for the Germans, there is also the added sense that had it not been for Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s invasion of the USSR, these crimes would never have been committed against German womanhood in the first place.

Three million German troops crossed the Soviet border in June 1941 in an attempt to extirpate the Russian state, and the Nazi commitment to

Total War produced atrocities so terrible that they were bound to be avenged once the Red Army reached German soil.

As so often in war, it was to be defenceless women, girls and even elderly ladies who were to pay in pain and outrage for the crimes of their male compatriots.

Many had abortions or were treated for the syphilis they caught. And as for the so-called Russenbabies – the children born out of rape – many were abandoned.

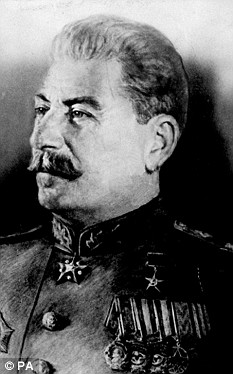

In his fine new book, World War Two: Behind Closed Doors, the historian Laurence Rees points out that although rape was officially a crime in the Red Army, in fact, Stalin explicitly condoned it as a method of rewarding the soldiers and terrorising German civilians.

Stalin said people should ‘ understand it if a soldier who has crossed thousands of kilometres through blood and fire and death has fun with a woman or takes some trifle’.

On another occasion, when told that Red Army soldiers sexually maltreated German refugees, he said: ‘We lecture our soldiers too much; let them have their initiative.’

While Stalin condoned rape as an instrument of state military policy, his police chief Lavrenti Beria was a serial rapist.

An American diplomat, Beria’s bodyguard and the Russian actress Tatiana Okunevskaya all bore witness of his methods of grabbing women off the street and shoving them into his limousine and then his bed.

‘You are a long way from anywhere, so whether you scream or not does not matter,’ Beria would tell the women when he got them back to his dacha. ‘You are in my power now. So think about that and behave accordingly.’

More than 100 school-aged girls and young women were drugged and raped by the man who ran the NKVD, the feared forerunner to the KGB.

‘All of which means, of course, that if reports of Red Army soldiers raping women in eastern Europe were sent to the NKVD in Moscow, they finally reached the desk of a rapist himself,’ says Rees.

The rape of Berlin’s female population – anyone between the ages of 13 and 70 was in danger – was cruelly vicious.

In one heart-breaking incident, a Berlin lawyer, who had somehow protected his Jewish wife from persecution throughout the Nazi period, was shot trying to protect her from rape by Red Army soldiers. As he lay dying of his wounds, he saw his wife being gang-raped.

‘They do not speak a word of Russian, but that makes it easier,’ one Red Army soldier wrote in a letter home in February 1945. ‘You don’t have to persuade them. You just point a revolver and tell them to lie down. Then you do your stuff and go away.’

It was unusual for Red Army soldiers to admit to rape in letters home, which is why this new German film is likely to shock Russian patriotic sensibilities.

Nor did the Germany’s surrender calm the Russians’ behaviour, at least in the short term.

‘Weeks before you entered this house, its tenants were living in constant fright and fear,’ the rich German publisher Hans-Dietrich Muller Grote wrote to President Truman about the place he stayed in during the Potsdam conference of July 1945.

‘By day and by night, plundering Russian soldiers went in and out, raping my sisters before their own parents and children, beating up my old parents. All furniture, wardrobes and trunks were smashed with bayonets and rifle butts, their contents soiled and destroyed in an indescribable manner.’