Benjamin Garland

Daily Stormer

January 31, 2015

* * *

Ten thousand Jews are making booze

In endless repetition

To fill the needs of a million Swedes

Who wanted prohibition

– Walter Liggett

This is the little known story of the law that almost crushed free speech in America in the 1920s and 30s, and the all-but-forgotten heroes who fought tooth and nail to get it overturned.

It begins with a little Minnesotan tabloid called the Duluth Rip-saw and ends in the Supreme Court of the United States.

The Duluth Rip-saw and the “Gag Law”

The discovery of the Mesabi Iron Range, with its seemingly endless supply of iron-ore, caused an economic and population boom in northern Minnesota around the turn of the 19th century. People from all over Europe emigrated there with the hope of making a fortune, or at least a good living.

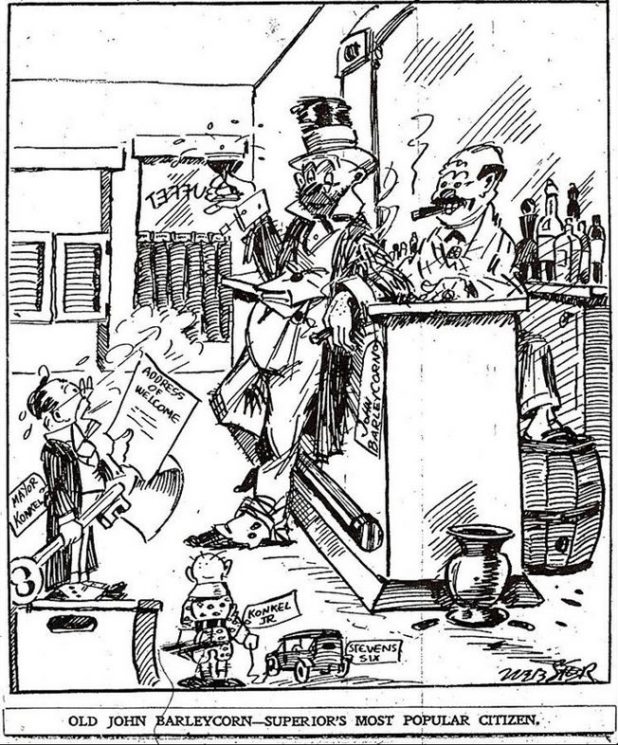

The area quickly degenerated into a hotbed of criminal activity. Booze, gambling and prostitution were rampant. Prohibition on alcohol, which hit Minnesota in 1917, greatly exacerbated the already widespread corruption and lawlessness by forcing the sale of liquor underground.

Minnesota was the crossroads for liquor transport between Canada, St. Louis and Chicago, and as such the buying off of politicians and police officials so they would look the other way was a necessity for bootleggers to operate without landing themselves in prison. As a result, the area became virtually ruled by criminals and gangsters, especially those of the Jewish persuasion.

A fundamentalist Christian who was disgusted with the systemic corruption in his town, John L. Morrison, began a biweekly newspaper called the Duluth Rip-saw as a means of fighting against it.

The paper helped to bring down the corrupt chief of police Robert McKercher and city auditor “King” Odin Halden, and did serious damage to many others that landed in its sights. Eventually, some big shots who had been targeted by the Rip-saw got fed up and decided to strike back against Morrison and his paper.

The first two, Judge Bert Jamison and Victor Power, simultaneously sued Morrison for libel, and both won after convincing a jury that the charges leveled against them by the Rip-saw had been false. Morrison retracted the statements, paid a $100 fine and issued a public apology.

The third to retaliate, Minnesota State Senator Mike Boylan, did not sue for libel but instead opted to draft a law that would effectively shut the Rip-saw–and any other paper like it–down for good. He and his political colleagues alleged that libel laws were not enough to protect them from “malicious, scandalous and defamatory” tabloids, such as Morrison’s.

So, in 1925, the Public Nuisance Law, better known as the “Minnesota Gag Law,” quietly passed in the Minnesota Senate 41-0, and in the House 87-22. The law was virtually unknown by the public at large as it went entirely unreported by the press. The “Gag Law” was a very broad, and very insidious piece of legislation–it made it so one judge, without a jury, could order a paper shut down simply by ruling it a “nuisance.”

One year almost to the day of the passing of the law, Morrison printed a story attacking the Mayor of Minnesota and was arrested and an injunction to shut down the Rip-saw on the grounds of the Nuisance Law was issued, but Morrison fell ill and died before getting the chance to contest the charge in court. Thus the Rip-saw petered out of existence, and the “Gag Law” sat unused for many years, as the corruption was so pervasive that all newspaper men were either paid off or too scared to say anything about it.

Almost all newspaper men, that is.

The Saturday Press

In 1916, Howard Guilford hired reporter Jay M. Near to help with his newspaper the Twin City Reporter, which Guilford had already been operating for a few years. Guilford and Near used this platform to fearlessly hammer away at the morally bankrupt political landscape of Minneapolis week after week with increasingly scathing exposés. The paper saw a bit of success and was mildly popular and influential but, of course, it made Near and Guilford no friends among the rotten-to-the-core political establishment of Minnesota.

A year later, in 1917, Guilford sold the Twin City Reporter to Near and a shady character named Jack Bevans. Shortly after that, Near bailed out of his share and moved to California, realizing that Bevans was a despicable creature who had been using the paper for blackmailing purposes.

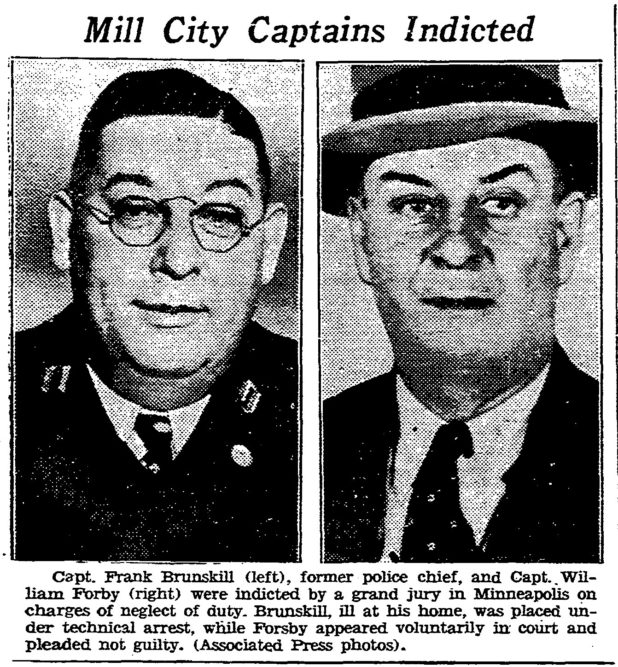

Over the next decade Bevans teamed up with local Jewish gangster Mose Barnett and Police Chief Frank Brunskill on a gambling house and continued using the paper for extortion and blackmail along with his new business partner, an Irish gangster named Ed Morgan.

A deal was struck: if Chief Brunskill allowed the game to go on unhindered then the gangsters would ensure that no robberies would occur in his district. Chief got a cut of the profits and no bank robberies and Bevans, Morgan and Barnett got to run their lucrative gambling outfit.

Near returned to Minneapolis in 1927 and upon reuniting with his friend Guilford, who wasn’t doing much at the time, they decided to launch another tabloid, which they would call the Saturday Press. They did so with the explicitly stated objective of using it to take down the circle of corruption surrounding their old paper, the Twin City Reporter.

As soon as word hit the street about the Saturday Press and its aims, Chief Brunskill ordered it banned, making it the first paper ever to be banned before a single print even went to press. Near and Guilford ignored this asinine order and continued to move the project forward as previously planned.

The first issue, as promised, exposed the criminal network of Barnett, Bevans and Co. and also reported on a threat they had received in an attempt to scare them away from publishing, in which their enemies had warned them: “Just a moment, boys, before you start something you won’t be able to finish.”

The following Monday, Guilford was ran off of the road by Jewish gangsters who then riddled his car with bullets, severely wounding him in the leg and gut.

Again, the Saturday Press didn’t even miss a beat and was on newsstands as scheduled the very next week. Guilford, still bleeding in his hospital bed, wrote the following in mocking defiance of the kosher thugs who tried to murder him: “I headed into the city on September 26, ran across three Jews in a Chevrolet; stopped a lot of lead and won a bed for myself in St. Barnabas Hospital, wherefore, I have withdrawn all allegiance to anything with a hook nose that eats herring.”

Jay Near also had some select words for who he called “the ochre-hearted rodents who fired those shots into the defenseless body of my buddy.” He let them know that if they “thought for a moment that they were ending the fight against gang rule in this city, they were mistaken.”

In other words, it was going to take a whole lot more than a few bullets and threats from some greasy, gefilte-fish eating gangsters to stop these two righteous men from standing up against evil.

Going After the Jews

The owner of a dry cleaning business named Sam Shapiro was shaken down, beaten and had his business vandalized by Jew gangster Barnett and his thug henchmen who were operating on behalf of the Twin Cities Cleaners and Dryers Association, which was attempting to “set prices” on dry cleaning. Shapiro could only find one person with the nerve to report on his case: Jay Near. The fact that everyone in the city was too cowardly to even mention Mose Barnett’s name, and that the police wouldn’t even indict him for harassing Shapiro, filled Near with indignant rage. He accused Brunskill of being complicit in the crime by protecting Barnett.

This prompted Brunskill to again order a ban on the Saturday Press, invoking an obscure city ordinance against obscenity. Of course, this charge was silly, as there was nothing obscene about the Saturday Press whatsoever. Near, who was in charge of the paper as Guilford was still in the hospital, again scoffed at Brunskill’s nonsensical order without even considering compliance. In fact, not only did Near ignore the chief’s order, he once again boldly attacked the crooked pig in the following issue.

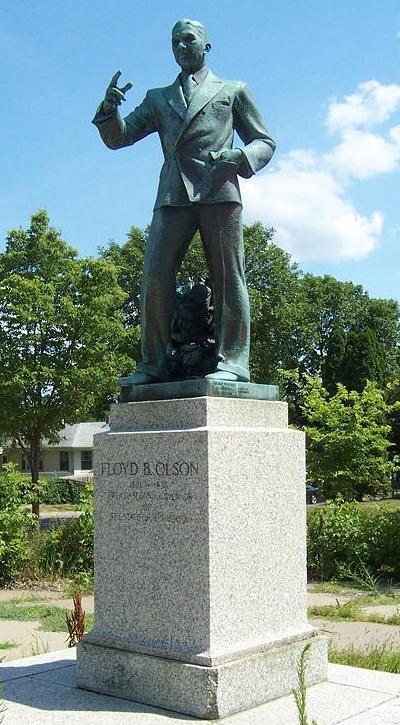

On November 19th, in the 9th issue of the Saturday Press, Near published an article titled “Facts Not Theories,” which targeted corrupt Hennepin County Attorney Floyd B. Olson, who would soon become his arch-nemesis. Olson, whom Guilford had previously (correctly) labeled as a “Jew-lover,” was a Yiddish speaking, actual shabbos goy:

The North Side neighborhood where Olson grew up was the home of a sizable Orthodox Jewish community, and Olson’s friendships with some of the local Jewish families led him to serve as a shabbos goy, assisting Jews on the Sabbath by performing actions they were not permitted to do. (Source: Wikipedia)

Near had been threatened to shut up by a Jew gangster on Olson’s behalf, prompting him to angrily respond by writing: “’I am a bosom friend of Mr. Olson’ snorted a gentleman of Yiddish blood, ‘and I want to protest against your article,’ blah, blah, blah, ad infinitum, ad nauseam,” adding that he was not “taking orders from men of Barnett faith, at least right now.”

“There have been too many men in this city and especially those in official life, who HAVE been taking orders and suggestions from JEW GANGSTERS,” Near charged, “therefore we have Jew Gangsters, practically ruling Minneapolis.”

He then noted the fact that it had been Jews who shot his buddy Guilford, Jews who assaulted Sam Shapiro, Jews who were behind just about every robbery, and Jews who were behind countless murders. It was “a gang of Jew gunmen who boasted that for five hundred dollars they would kill any man in the city,” he snarled, and it was “Mose Barnett, a Jew, who boasted that he held the Chief of Police of Minneapolis in his hand—had bought and paid for him.

“Practically every vendor of vile hooch, every owner of a moonshine still, every snake-faced gangster and embryonic yegg in the Twin Cities is a JEW.

“I simply state a fact when I say that ninety percent of the crimes committed against society in this city are committed by Jew gangsters.

“It was a Jew who employed JEWS to shoot down Mr. Guilford. It was a Jew who employed a Jew to intimidate Mr. Shapiro and a Jew who employed JEWS to assault that gentlemen when he refused to yield to their threats. It was a JEW who wheedled or employed Jews to manipulate the election records and returns in the Third ward in flagrant violation of law. It was a Jew who left two hundred dollars with another Jew to pay our chief of police just before the last municipal election, and:

“It is Jew, Jew, Jew, as long as one cares to comb over the records.”

He then threw down the gauntlet, making it perfectly clear that neither he, nor Guilford, would “step one inch out of our chosen path to avoid a fight IF the Jews want to battle.”

Guilford, writing in that same issue, warned the “Yid” gangsters and their shabbos goy accomplices that “up to the present we have been merely tapping on the window. Very soon we shall start smashing glass.”

Gag Law Invoked, Saturday Press Shut Down

Going after the Jews and the powerful Floyd Olson was the straw that broke the camel’s back for Near and Guilford. Three days after the issue containing the article quoted above hit the streets, Olson invoked the infamous “Gag Law” in an attempt to have the Saturday Press shut down as a “ public nuisance” for having an “overly anti-Semitic tone.”

Olson requested that there be a temporary restraining order against the paper until it could be officially shut down, a request that was promptly granted by Minnesota Judge Mathias Baldwin. Baldwin’s decision ordered the stoppage of Near and Guilford “producing, publishing, editing, circulating, having in their possession, selling and giving away” the Saturday Press, or any other similar publication.

Near and Guilford demurred on the grounds that the “Gag Law” was clearly unconstitutional. Baldwin refused to appeal but eventually allowed the case to go to the Minnesota Supreme Court, which unanimously upheld the ruling. In a statement reminiscent of the Great Holocaust Trial of Ernst Zundel over half a century later, wherein a prosecutor yelled that “the truth is no defense,” the Supreme Court Judge of Minnesota told Near and Guilford that “there is no constitutional right to publish a fact merely because it is true.”

The fight was far from over though. Near was well aware that the law had been passed specifically to silence the Duluth Rip-saw and that Morrison had “sighed and passed on” before he was even able to fight against it. Near, ever-the-fighter, assured his opponents that he had “no intention of being so accommodating”

Near and Guilford Vindicated

Before going further with our story, I believe it worthy to note how Near and Guilford–the writers who had been condemned by so many–were vindicated on many of their charges before and after the silencing of the Saturday Press.

In 1920, Howard Guilford had gotten county attorney William “Bud” Nash removed from his position after ousting him as a bribe taker with the Twin City Reporter. Floyd Olson, who was assistant county prosecutor at the time, moved up into Nash’s former position (so, in a way, ironically, Olson had Guilford to thank for his job).

Shortly after the Saturday Press was shut down by the “Gag Law,” none other than Chief Brunskill became the target of a Grand Jury probe on the same charges that Near and Guilford had repeatedly accused him of in the Saturday Press, proving they had been correct all along.

Seventy-five people were charged in the Shapiro case, as well as Jew thug Mose Barnett and three other gangsters, again showing that Near and Guilford had been scrupulous and correct in their assertions.

Unfortunately, but not surprisingly, these revelations had no bearing on Near and Guilford’s case nor the gag order, which still stood.

The Case Finds Help

Guilford eventually dropped out of the battle, wounded and discouraged by the slow pace of the litigation, but Near was determined to fight to the bitter end and take it all the way to the top. He contacted the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in New York and they sympathized with his struggle and agreed to help, recognizing the implications that the law had on American freedoms.

The ACLU was ill-funded though, relying solely on donations, so it was going to be an uphill–probably losing–battle. But fortunately the case also soon caught the attention of another man, one with much more resources than the ACLU: Colonel Robert “Bertie” McCormick, millionaire owner of the Chicago Tribune.

Robert McCormick was a right-wing, anti-communist, freedom-loving American man who probably didn’t care much for Jews either. McCormick was horrified at the idea of the restriction of freedom of speech and had already previously been engrossed in two bitter court battles revolving around it.

McCormick consulted with his lawyer Weymouth Kirkland on the matter, who told him “Bert, the mere statement of this case makes my blood boil. Whether the articles are true or not, for a judge without jury, to suppress a newspaper without writ of injunction, is unthinkable. If this decision stands, any newspaper in Minnesota which starts a crusade against gambling, vice or other evils, may be closed down . . . without a trial by jury.”

McCormick, after convincing the American Newspaper Publishers Association (ANPA) to back him, decided to jump into the battle with both feet and do whatever it took to overturn this vicious assault on the most basic and fundamental of all American freedoms.

To the Supreme Court

After being turned down by the Minnesota Supreme Court twice, and with the help of McCormick, Kirkland and the ANPA, on April 26, 1930, Near’s case was officially docked by the Supreme Court of the United States.

Shortly thereafter, something happened that can almost be seen as an act of God: upon convening court on March 8, it was announced that Associate Justice Edward T. Sanford had died suddenly after collapsing in his dentist’s chair. Five hours later it was learned that a second member of the court, William Howard Taft, former President of the United States who was then serving as Chief Justice, had also died after slipping into a coma at his home.

These two deaths were without a doubt an important factor in the final decision. Sanford and Taft voted as a block with the four other conservatives, known as the “Four Horsemen,” against three dissenters, almost without fail. The two deaths thus knocked down the likely predestined vote of 6-3 to 4-3, with Sanford and Taft’s replacements holding the decisive votes.

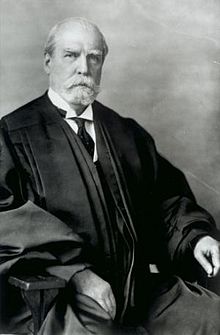

Associate Justice Sanford was replaced by Owen J. Roberts and Chief Justice Taft was replaced by Charles Evan Hughes. Hughes was generally of the opinion that aside from certain regulations during wartime or “falsely shouting fire in a crowded theater,” all speech was justly protected by the 1st and 14th Amendments.

Ultimately, after a court drama split nearly down the middle, Hughes and Roberts both voted against the Nuisance Law, making the decision, which was handed down on June 1, 1931, as narrow as it gets: 5-4.

Had it gone in the other direction, the results would have been catastrophic for freedom of speech. As mentioned before, it would have made it so one judge could single-handedly silence any dissent. Furthermore, bringing the case to the Supreme Court virtually guaranteed that if the Minnesota law had been upheld, the other 49 states would’ve soon passed similar laws, and the Supreme Court precedent would’ve made them very hard to overturn.

McCormick, in a full page headline the next day, rejoiced:

“The decision of Chief Justice Hughes will go down in history as one of the greatest triumphs of free thought. The Minnesota gag law was passed by a crooked legislature to protect criminals in office and supported by a state court as feeble in public spirit as it was weak in public acumen.

We must not blind ourselves to the fact that subversive forces have gone far in this country when such a statute could be passed by any legislature and upheld by any court, and must be on guard against further encroachment.”

Two Murders

Near had the Saturday Press, the “paper that refused to stay gagged,“ back in print in October of 1932. He and Guilford, partnering up off and on, continued to relentlessly expose Olson, who was now governor of Minnesota, as being a criminal and willing tool of the Jews.

Guilford decided to run for office a couple of years later and announced on the radio that he was going to “tell the truth about Governor Floyd Olson’s connections with the underworld.” The very next day, Sep. 6, 1934, he was killed in a professional hit. An assassin pulled up next to him at an intersection and shot him point blank in the head with a shotgun. The police barely investigated the crime, and even actively worked to cover it up by turning away important witnesses and leads.

Fifteen months later, another crusader against government crime and corruption, nationally acclaimed journalist Walter W. Liggett, was shot dead in front of his family while unloading groceries out of his car at his home. Liggett also, like Guilford, had been a fierce opponent of Floyd Olson.

In a letter to a friend a few days before his murder, Liggett had written: “I have determined to drive Olson and his gang out of public life if it is the last thing I do. It will be a tough job—but I have already weakened his popularity and in another year I think I can finish him off—that is, if he doesn’t have me shot in the meantime as he did poor Howard Guilford. There is always that danger.”

Previously, as a result of his formidable opposition to high-level criminals such as Olson, Liggett had been repeatedly stalked (at least once by the notorious Jewish “Purple Gang”), issued death threats, harassed by public officials, had his phones tapped, his machines sabotaged, and was even arrested and dragged through the courts on the filthy trumped up charge of abducting two teenage girls and then sodomizing one in front of the other – a charge later shown to have been completely false (the girls were both juvenile delinquents, and one later admitted to being blackmailed with jail time to tell the phony story).

While awaiting trial for the trumped up charge, Liggett was viciously beaten by notorious Jewish crime boss of Minneapolis Kid Cann and seven of his gangster buddies after they solicited a bribe that he categorically rejected. The judge maliciously refused to extend the trial, forcing Liggett to go to court so badly injured that he could barely stand up or speak. Nevertheless, the trial was a farce and a jury found him not guilty.

After he was murdered Liggett’s wife Edith, who was a direct witness, immediately fingered Kid Cann as the triggerman, but Cann was never convicted because he had an alibi that gave the jury reasonable doubt. Edith suspected the shabbos goy Jew puppet Floyd Olson as being the one who ordered the hit until the day she died.

Both Harold Guilford and Walter Liggett had waged an unrelenting campaign against corruption in Minnesota, both refused to stay quiet in the face of evil, and both paid the ultimate price.

Legacy

Guilford and Liggett’s murders, with Liggett’s being the tipping point, prompted a crack down on corruption in Minneapolis, resulting in dozens of bootleggers and corrupt officials being arrested.

Journalist Will Irwin wrote of Liggett: “Living he may have failed. But dead, he may go down as the man who led the way for a clean-up.”

Jay Near continued to crusade against corruption until the day he died (of natural causes) on Apr. 17, 1936. He was 62.

Floyd B. Olson served three terms as Governor of Minnesota and died of stomach cancer at 44 on Aug. 22, 1936, cutting short his political career which ultimately had its sights on the White House. He is an icon of the liberal left and there are numerous statues of him erected around Minnesota.

Although Near died virtually penniless and Guilford and Liggett were brutally assassinated, and all of them are condemned by history, with many accounts even accusing them of being blackmailers–a ludicrous libel that doesn’t correspond with any of what is known of their lives–these brave men made a mark on America that reverberates to this very day, and for this we all owe them a debt of gratitude.

“The precedent of Near v. Minnesota,” writes Fred Friendly, in his definitive book on the “Gag Law” case, Minnesota Rag, “has withstood onslaughts from Presidents, legislatures and even the judiciary itself in its attempts to enforce basic rights which seemed to clash with the First Amendment.”

This fascinating story highlights just how fragile our freedoms really are and how quickly we can lose them unless we are willing to fight.

* * *

Select Sources/Further Reading:

Minnesota Rag by Fred W. Friendly

Stopping the Presses: The Murder of Walter W. Liggett by Martha Liggett Woodbury

The Colonel’s Finest Campaign: Robert R. McCormick and Near v. Minnesota by Eric B. Easton

The Minnesota Gag Law and the 14th Amendment by John E. Hartman

Last of the Muckrakers: An Appreciation of Walter Liggett

Shall Make No Law by Robert O’Connor

The Stromberg and Near Cases by Richard Cortner

Jews Gloat About Taking Over Anti-Semitic Robert McCormick’s Chicago Tribune