Andrew Joyce

Occidental Observer

December 22, 2014

Of all the accusations commonly leveled against a Jews as a group, perhaps the one they find most frightening is the accusation that they are disloyal, or aren’t ‘quite’ like the rest of us. Arguably, a large part of the Jewish evolutionary strategy consists of maintaining a pose, or pretence, to be fully in and of the nation and its people. In this context, accusations of disloyalty, or even gentle reminders that Jews have an unassimilated separate ‘identity,’ disturb the strategy in such a fundamental manner that the entire Jewish ‘game’ seems to be in jeopardy. Since the era of Jewish ‘emancipation,’ the pursuance and success of the strategy has been highly dependent on the rest of society granting Jews citizenship on equal terms, and failing to note that Jews have a different agenda and aren’t playing by the same rules. Jews therefore jealously censor discussion of their loyalty, citizenship, identity, and place within the nation.

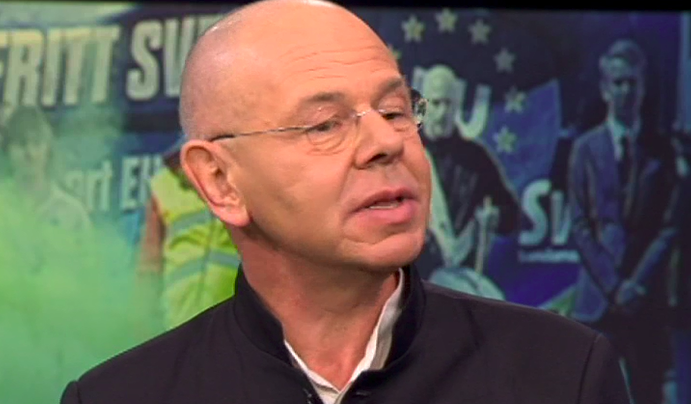

Given these realities, I wasn’t surprised this week when Jewish leaders in Sweden got a little hot under the collar after Björn Söder, secretary of the anti-immigrant Sweden Democrats (SD) and deputy speaker in Parliament, went on record with some fairly innocuous comments about citizenship and identity which, disturbingly for the Hebrews, happened to mention Jews.

In an interesting and frank newspaper interview published on Sunday, Söder is reported to have said:

I think that most people with Jewish origin who have become Swedes leave their Jewish identity behind. But if they don’t, it doesn’t have to be an issue. One must distinguish between citizenship and nationhood. They can still be Swedish citizens and live in Sweden. Sami and Jews have lived in Sweden for a long time.

The interview was more generally concerned with the growing success of the SD, and the party’s attitude towards identity and the multicultural project in Sweden. When the reporter informed Söder that the comedian Soran Ismail used to say that he was 100 per cent Swedish and 100 Kurdish, the latter responded by stating “I do not think you can belong to two nations that way. However, the Kurds can be Swedish citizens. The problem is if there will be too many in Sweden who belong to other nations.” Asked about his party’s approach to the foreign-born residents of Malmö (constituting a third of the population), Söder replied:

They must adapt and become a part of the Swedish nation. We have an open Swedishness, an individual can become a Swedish citizen regardless of background. But it requires that they assimilate. And the problem with Malmö is that we have brought too many. If we bring together very many from other nations together in Sweden, we just get foreign enclaves in Sweden. … I think these people, and many Swedes, will lose identity eventually. They will ask: what country belongs to me? It becomes an identity-less society. And obviously there is a problem in Malmö because the economy is so lousy. The rest of the country must keep Malmö together fiscally. Malmö had once been so good, and in the past these great problems weren’t so obvious.

The interviewer also tried to draw Söder on ‘Silla Mackan,’ a blog entry written over fifteen years ago when Söder was in his 20s. The text concerned his travel by summer train in Skåne. He looks out at the Skåne countryside with farms that under a clear blue sky “looked like palaces and temples.” The sights instilled in Söder a pride: “A pride to be Swedish. Having been born Swedish. To have ancestors who built Sweden.” Arriving in multicultural Malmö, Söder’s mood deteriorates. He gets hungry — but finds only “foreign food” at the city festival: “Latin food, tacos, falafel, Indian food, Thai dishes, Nigerian specialties, kebabs.” He becomes increasingly hungry, looking in vain for something closer to home. Suddenly, like “a small light in the otherwise dark environment” he sees a sign: ‘Silla Sandwiches.’ Overjoyed, he goes “beyond all garlic fragrant food stalls” and buys its herring sandwich. But, returning his gaze to the swirling ethnic miasma around him, his joy dissipates and he is once more bleak:

Outside McDonald’s dark clouds had gathered. By all accounts, it was probably a gathering place or rather a haunt for the whole world of different people, except the Swedes of course. I do not know where the Swedes had gone. I crossed the square and went down a pedestrian street. It was clear to me that the Swedes had fled the field. Everywhere were big black clouds over an otherwise clear starry rich firmament. The Sound of the South-American and Indian music mixed with languages from around the world and the feeling that you were in a land far, far away creeps in. Nowhere was a bright cloud to glimpse. Everywhere hung a dark cloud. My stomach was turning inside out and the tears started running down my cheek.

He hurries to board a train to get away from Malmö, from an evening gone from “warmth and light,” to “dark and cold.”

Söder now distances himself somewhat from the more ‘melodramatic’ aspects of the text. He informed the reporter that in some respects the blog was “pathetic” and that “I was not so old and have changed and matured since then. Well, I was more radical then, as is often the case with the young.” Asked whether he still found it difficult to relate to people of other ethnicities living in Sweden, Söder responded candidly that there were social codes and patterns of thought and living which represented serious barriers for the admission of such people to the national community.

Pressed on what the SD would do in Malmö, Söder states that:

First and foremost would be necessary to tackle the current problems without adding new ones. We need an end to the EBO (through which asylum seekers are allowed to arrange their own accommodation) and a cap on admissible refugees. Then we would introduce a repatriation grant. … We must make it easier for those considering moving back to their home country. By doing this we arrive at a better position in which to create a society of common identity … . Many of the immigrants realize themselves that we cannot have so many immigrants in Sweden in such a short time. We are getting more and more members of the SD with an immigrant background. They agree on this issue … .We have such large groups coming to Sweden now that we need to stop … . We need to make demands: if you want to stay here now you shall have to integrate into Swedish society. We need to stop making it easier for people to never get into Swedish society, by providing government information in Arabic and the like. People need to learn Swedish.

The newspaper report of the interview notes that this rhetoric is “harder, more radical” than that employed by the SD in recent years. Part of this is due to increased nationalist confidence. From polling just 1% in the 2002 elections, the most recent opinion polls place the SD as not only the third largest party in Sweden, but as taking an impressive 17.7% of voter support. In the past “Sweden Democrats were often beaten and kicked from their jobs because of their party affiliation,” but now the party sphere has “become enormously greater.” Confidence is also greater after the deputy party leader Mattias Karlsson went on the offensive two weeks ago, using growing SD influence to veto the government’s budget and force a round of fresh elections in March. One leading member reportedly informed the press: “Now, the battle for second place in Swedish politics begins in earnest. Now we draw the political map.”

The party’s growing success, and its stance on citizenship and identity have, predictably, drawn fire from panicked Jewish organizations and leftists. In order to distract attention from Söder’s commonsense thinking, reactions to the interview have singled out his throwaway reference to Jews as if that were the primary focus of the piece. Willy Silberstein, the chairman of the Swedish Committee Against Anti-Semitism, has now attacked the Sweden Democrats as a “Nazi organization.” Silberstein has been quoted as saying, “I am Jewish and born in Sweden … . I am just as much Swedish as Björn Söder … . To walk into a synagogue, if one wants to, is 100% part of Swedish life.”

Lea Posner Korosi, president of the Official Council of Jewish Communities in Sweden, followed Silberstein’s comments by classifying Soder’s comments as “good old right-wing anti-Semitism,” adding, “I am appalled that Sweden’s third-largest party can express itself in this way about Jews and other minorities … . We have to take them really seriously. This is not a small group of fanatics you can dismiss.” Even the Prime Minister, Stefan Löfven, whose increasingly illegitimate government is formed via a minority coalition with the Greens, accused the SD of being “neo-fascist.” A simpering Löfven said he found Söder’s remarks “very, very scary.”

Why are Söder’s remarks so ‘scary’? Because of their extremely clear articulation of a view of citizenship and nationality entirely at odds with that favored by Jews and others benefitting from the multicultural project — essentially the idea of the proposition nation pioneered by several Jewish intellectuals (e.g., Horace Kallen [see here, p. 248ff], Eric Hobsbawm and Leo Strauss). The report carrying the interview with Söder also carried commentary from left-wing historian Fredrik Persson-Lahusen. Persson-Lahusen’s research focuses on nationalism and collective identities. Asked to read Björn Söder’s interview answers, Persson-Lahusen says:

What Björn Söder expresses here is a radical and consistent nationalism. It is an uncompromising vision of nationality and community. It illustrates clearly how different the SD is from other Swedish parliamentary parties. There are two types of nationalism: French-American and German. In the French view nationalism is all about the place you live in, citizenship, shared values. In the German view, there is more emphasis on blood and soil. It’s about your origins. It is impossible to attain citizenship in the German sense unless you have the right inheritance. What Björn Söder expresses moves more towards the traditional German vision. Söder says, that one can be a Swedish citizen, even if, as he puts it, one belongs to another nation. It is a pragmatic approach. But later in the interview he says that peoples and states borders should be consistent. Here he reveals the essence of radical nationalism. And that’s where the concern is.

In Fredrik Persson-Lahusen’s eyes, the SD are working ideologically in the long-term. He believes that panicked discussions about whether or not the party is fascist are unimportant — at least in the context that the opponents of the party have failed to tackle the fact that that nationalism, and popularizing nationalism, is central to the SD’s political project. According to Persson-Lahusen, one of the greatest SD successes has not been in the electoral sphere, but in moving the entire political discussion toward a more radical nationalism.

Persson-Lahusen notes that:

They’re actually succeeding in doing it. This is particularly noticeable if you look at how the party’s political opponents have chosen to respond to the SD’s onslaught. Jason “Timbuktu” Diakités speech in Parliament, for example, when he took out his Swedish passport and underlined its Swedishness. I understand the reflex: you want to see an alternative nationalism which is better. But at the same time Diakités speech highlights nationalism as something important, and that is where the SD wants the discussion.

Of course, the Jewish organizations named above are fully aware of the dangers posed to their position and interests by the growth in ‘blood and soil’ nationalism. They loathe it because it automatically rules them out of the game. They become de facto outsiders, and a group strategy based on the pretence of being exactly similar to those around them becomes untenable. In these circumstances they are forced to abandon that nation state.

They will, however, continue with ‘unimportant’ (Persson-Lahusen’s word) protestations and debates about the ‘fascism’ of the SD and similar parties because of the saturation of modern culture with negative connotations with words with ‘fascist,’ ‘Nazi,’ ‘anti-Semite,’ and ‘racist.’ Throwing these words around, they believe, is the easy and lazy way of depriving these parties of legitimacy, respect, and support.

The problem they face, however, is that when racial realities make their presence felt, as they have been felt acutely in places like Malmö, old taboos quickly disintegrate. As in the case of the SD, those once “beaten and kicked from their jobs because of their party affiliation” soon find themselves surrounded by more and more fellow members and supporters. When people, like the young Björn Söder, find themselves in their own nation feeling that they are “in a land far, far away,” they gain a sense of having nothing to lose, and name-calling begins to lose its potency. Confidence rises. Revolutions happen. Nations are reborn.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History