Daily Stormer

February 1, 2014

Excerpt from The History of the Conquest of Mexico (Vol. 3) by William H. Prescott:

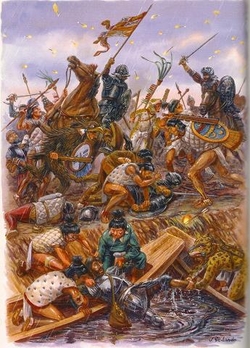

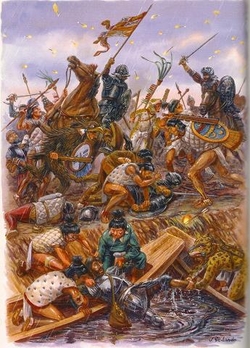

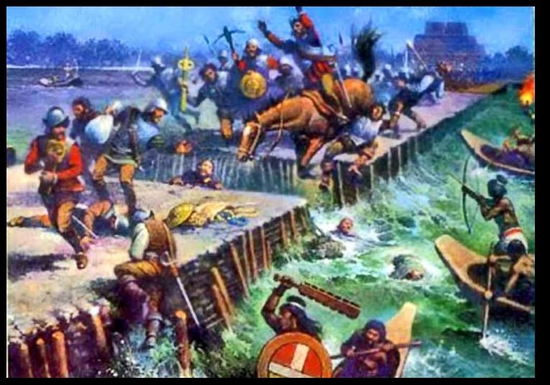

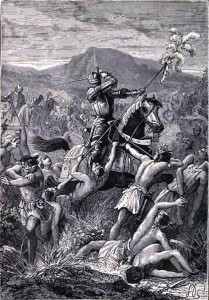

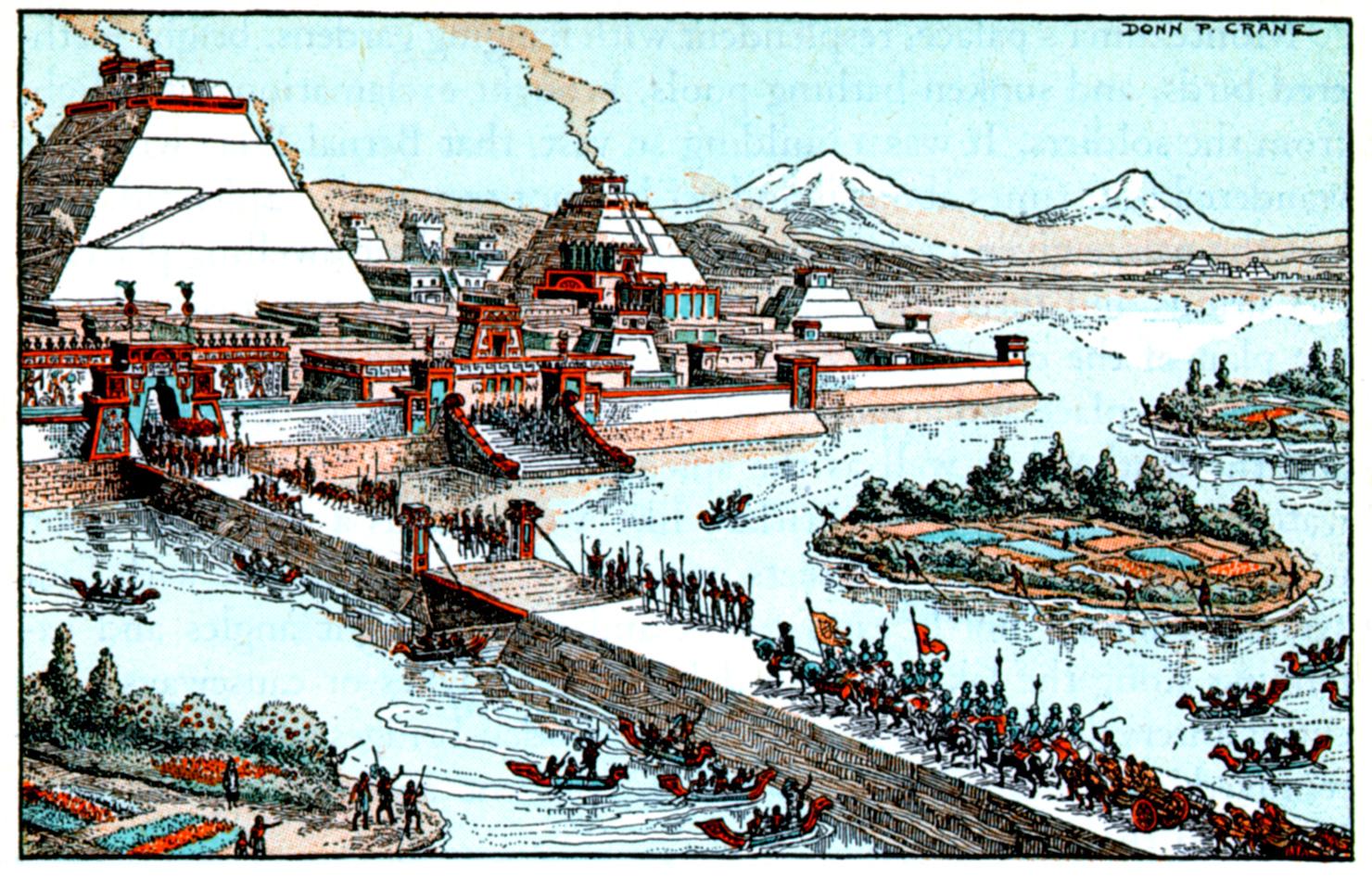

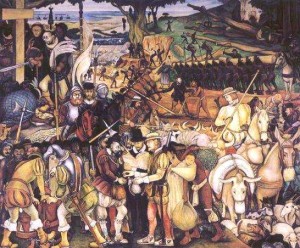

The army, taken by surprise, and shaken by the fury of the assault, was thrown into the utmost disorder. Friends and foes, white men and Indians, were mingled together in one promiscuous mass. Spears, swords, and war-clubs were brandished together in the air. Blows fell at random. In their eagerness to escape, they trod down one another. Blinded by the missiles which now rained on them from the azoteas, they staggered on, scarcely knowing in what direction, or fell, struck down by hands which they could not see. On they came, like a rushing torrent sweeping along some steep declivity, and rolling in one confused tide towards the open breach, on the farther side of which stood Cortes and his companions, horror-struck at the sight of the approaching ruin. The foremost files soon plunged into the gulf, treading one another under the flood, some striving ineffectually to swim, others, with more success, to clamber over the heaps of their suffocated comrades. Many, as they attempted to scale the opposite sides of the slippery dike, fell into the water, or were hurried off by the warriors in the canoes, who added to the horrors of the rout by the fresh storm of darts and javelins which they poured on the fugitives.

Cortes, meanwhile, with his brave followers, kept his station undaunted on the other side of the breach. “I had made up my mind,” he says, “to die, rather than desert my poor followers in their extremity!” With outstretched hands he endeavored to rescue as many as he could from the watery grave, and from the more appalling fate of captivity. He as vainly tried to restore something like presence of mind and order among the distracted fugitives. His person was too well known to the Aztecs, and his position now made him a conspicuous mark for their weapons. Darts, stones, and arrows fell around him thick as hail, but glanced harmless  from his steel helmet and armor of proof. At length a cry of “Malinche,” “Malinche,” arose among the enemy ; and six of their number, strong and athletic warriors, rushing on him at once, made a violent effort to drag him on board their boat. In the struggle he received a severe wound in the leg, which, for the time, disabled it. There seemed to be no hope for him ; when a faithful follower, Cristoval de Olea, perceiving his general’s extremity, threw himself on the Aztecs, and with a blow cut off the arm of one savage, and then plunged his sword in the body of another. He was quickly supported by a comrade named Lerma, and by a Tlascalan chief, who, fighting over the prostrate body of Cortes, despatched three more of the assailants; though the heroic Olea paid dearly for his self-devotion, as he fell mortally wounded by the side of his general.

from his steel helmet and armor of proof. At length a cry of “Malinche,” “Malinche,” arose among the enemy ; and six of their number, strong and athletic warriors, rushing on him at once, made a violent effort to drag him on board their boat. In the struggle he received a severe wound in the leg, which, for the time, disabled it. There seemed to be no hope for him ; when a faithful follower, Cristoval de Olea, perceiving his general’s extremity, threw himself on the Aztecs, and with a blow cut off the arm of one savage, and then plunged his sword in the body of another. He was quickly supported by a comrade named Lerma, and by a Tlascalan chief, who, fighting over the prostrate body of Cortes, despatched three more of the assailants; though the heroic Olea paid dearly for his self-devotion, as he fell mortally wounded by the side of his general.

Ixtlilxochitl, who would fain make his royal kinsman a sort of residuary legatee for all unappropriated, or even doubtful, acts of heroism, puts in a sturdy claim for him on this occasion. A painting, he says, on one of the gates of a monastery of Tlatelolco, long recorded the fact that it was the Tezcucan chief who saved the life of Cortes. But Camargo gives the full credit of it to Olea, on the testimony of ” a famous Tlascalan warrior,” present in the action, who reported it to him. The same is stoutly maintained by Bernal Diaz, the townsman of Olea, to whose memory he pays a hearty tribute, as one of the best men and bravest soldiers in the army. (Hist, de la Conquista, cap. 152, 204.) Saavedra, the poetic chronicler, — something more of chronicler than poet, — who came on the stage before all that had borne arms in the Conquest had left it, gives the laurel also to Olea, whose fate he commemorates in verses that at least aspire to historic fidelity:

The report soon spread among the soldiers that their commander was taken ; and Quinones, the captain of his guard, with several others, pouring in to the rescue, succeeded in disentangling Cortes from the grasp of his enemies, who were struggling with him in the water, and, raising him in their arms, placed him again on the causeway. One of his pages, meanwhile, had advanced some way through the press, leading a horse for his master to mount. But the youth received a wound in the throat from a javelin, which prevented him from effecting his object. Another of his attendants was more successful. It was Guzman, his chamberlain ; but, as he held the bridle while Cortes was assisted into the saddle, he was snatched away by the Aztecs, and, with the swiftness of thought, hurried off by their canoes. The general still lingered, unwilling to leave the spot while his presence could be of the least service. But the faithful Quinones, taking his horse by the bridle, turned his head from the breach, exclaiming, at the same time, that “his master’s life was too important to the army to be thrown away there.”

Yet it was no easy matter to force a passage through the press. The surface of the causeway, cut up by the feet of men and horses, was knee-deep in mud, and in some parts was so much broken that the water from the canals flowed over it. The crowded mass, in their efforts to extricate themselves from their perilous position, staggered to and fro like a drunken man. Those on the flanks were often forced by the lateral pressure of their comrades down the slippery sides of the dike, where they were picked up by the canoes of the enemy, whose shouts of triumph proclaimed the savage joy with which they gathered in every new victim for the sacrifice. Two cavaliers, riding by the general’s side, lost their footing, and rolled down the declivity into the water. One was taken and his horse killed. The other was happy enough to escape. The valiant ensign, Corral, had a similar piece of good fortune. He slipped into the canal, and the enemy felt sure of their prize, when he again succeeded in recovering the causeway, with the tattered banner of Castile still flying above his head. The barbarians set up a cry of disappointed rage as they lost possession of a trophy to which the people of Anahuac attached, as we have seen, the highest importance, hardly inferior in their eyes to the capture of the commander-in-chief himself.

Yet it was no easy matter to force a passage through the press. The surface of the causeway, cut up by the feet of men and horses, was knee-deep in mud, and in some parts was so much broken that the water from the canals flowed over it. The crowded mass, in their efforts to extricate themselves from their perilous position, staggered to and fro like a drunken man. Those on the flanks were often forced by the lateral pressure of their comrades down the slippery sides of the dike, where they were picked up by the canoes of the enemy, whose shouts of triumph proclaimed the savage joy with which they gathered in every new victim for the sacrifice. Two cavaliers, riding by the general’s side, lost their footing, and rolled down the declivity into the water. One was taken and his horse killed. The other was happy enough to escape. The valiant ensign, Corral, had a similar piece of good fortune. He slipped into the canal, and the enemy felt sure of their prize, when he again succeeded in recovering the causeway, with the tattered banner of Castile still flying above his head. The barbarians set up a cry of disappointed rage as they lost possession of a trophy to which the people of Anahuac attached, as we have seen, the highest importance, hardly inferior in their eyes to the capture of the commander-in-chief himself.

Cortes at length succeeded in regaining the firm ground, and reaching the open place before the great street of Tacuba. Here, under a sharp fire of the artillery, he rallied his broken squadrons, and, charging at the head of the little body of horse, which, not having been brought into action, were still fresh, he beat off the enemy. He then commanded the retreat of the two other divisions. The scattered forces again united ; and the general, sending forward his Indian confederates, took the rear with a chosen body of cavalry to cover the retreat of the army, which was effected with but little additional loss.”

Andres de Tapia was despatched to the western causeway to acquaint Alvarado and Sandoval with the failure of the enterprise. Meanwhile the two captains had penetrated far into the city. Cheered by the triumphant shouts of their countrymen in the adjacent streets, they had pushed on with extraordinary vigor, that they might not be outstripped in the race of glory. They had almost reached the market-place, which lay nearer to their quarters than to the general’s, when they heard the blast from the dread horn of Guatemozin, followed by the overpowering yell of the barbarians, which had so startled the ears of Cortes ; till at length the sounds of the receding conflict died away in the distance. The two captains now understood that the day must have gone hard with their countrymen. They soon had further proof of it, when the victorious Aztecs, returning from the pursuit of Cortes, joined their forces to those engaged with Sandoval and Alvarado, and fell on them with redoubled fury. At the same time they rolled on the ground two or three of the bloody heads of the Spaniards, shouting the name of “Malinche.” The captains, struck with horror at the spectacle, — though they gave little credit to the words of the enemy, — instantly ordered a retreat. Indeed, it was not in their power to maintain their ground against the furious assaults of the besieged, who poured on them, swarm after swarm, with a desperation of which, says one who was there, “although it seems as if it were now present to my eyes, I can give but a faint idea to the reader. God alone could have brought us off safe from the perils of that day.” The fierce barbarians followed up the Spaniards to their very intrenchments. But here they were met, first by the cross-fire of the brigantines, which, dashing through the palisades planted to obstruct their movements, completely enfiladed the causeway, and next by that of the small battery erected in front of the camp, which, under the management of a skilful engineer, named Medrano, swept the whole length of the defile. Thus galled in front and on flank, the shattered columns of the Aztecs were compelled to give way and take shelter under the defences of the city.

The greatest anxiety now prevailed in the camp regarding the fate of Cortes; for Tapia had been detained on the road by scattered parties of the enemy, whom Guatemozin had stationed there to interrupt the communication between the camps. He arrived at length, however, though bleeding from several wounds. His intelligence, while it reassured the Spaniards as to the general’s personal safety, was not calculated to allay their uneasiness in other respects.

The greatest anxiety now prevailed in the camp regarding the fate of Cortes; for Tapia had been detained on the road by scattered parties of the enemy, whom Guatemozin had stationed there to interrupt the communication between the camps. He arrived at length, however, though bleeding from several wounds. His intelligence, while it reassured the Spaniards as to the general’s personal safety, was not calculated to allay their uneasiness in other respects.

Sandoval, in particular, was desirous to acquaint himself with the actual state of things and the further intentions of Cortes. Suffering as he was from three wounds, which he had received in that day’s fight, he resolved to visit in person the quarters of the commander-in-chief. It was mid-day — for the busy scenes of the morning had occupied but a few hours — when Sandoval remounted the good steed on whose strength and speed he knew he could rely. It was a noble animal, well known throughout the army, and worthy of its gallant rider, whom it had carried safe through all the long marches and bloody battles of the Conquest.

On the way he fell in with Guatemozin’s scouts, who gave him chase, and showered around him volleys of missiles, which, fortunately, found no vulnerable point in his own harness or that of his well-barbed charger.

On arriving at the camp, he found the troops there much worn and dispirited by the disaster of the morning. They had good reason to be so. Besides the killed, and along file of wounded, sixty-two Spaniards, with a multitude of allies, had fallen alive into the hands of the enemy, — an enemy who was never known to spare a captive. The loss of two field-pieces and seven horses crowned their own disgrace and the triumph of the Aztecs. This loss, so insignificant in European warfare, was a great one here, where both horses and artillery, the most powerful arms of war against the barbarians, were not to be procured without the greatest cost and difficulty.

Cortes, it was observed, had borne himself throughout this trying day with his usual intrepidity and coolness. The only time he was seen to falter was when the Mexicans threw down before him the heads of several Spaniards, shouting, at the same time, “Sandoval,” “Tonatiuh,” the well-known epithet of Alvarado. At the sight of the gory trophies he grew deadly pale; but, in a moment recovering his usual confidence, he endeavored to cheer up the drooping spirits of his followers. It was with a cheerful countenance that he now received his lieutenant; but a shade of sadness was visible through this outward composure, showing how the catastrophe of the puente cuidada, ” the sorrowful bridge,” as he mournfully called it, lay heavy at his heart.

To the cavalier’s anxious inquiries as to the cause of the disaster, he replied, “It is for my sins that it has befallen me, son Sandoval;” for such was the affectionate epithet with which Cortes often addressed his best-beloved and trusty officer. He then explained to him the immediate cause, in the negligence of the treasurer. Further conversation followed, in which the general declared his purpose to forego active hostilities for a few days. “You must take my place,” he continued, “for I am too much crippled at present to discharge my duties. You must watch over the safety of the camps. Give especial heed to Alvarado’s. He is a gallant soldier, I know it well; but I doubt the Mexican hounds may, some hour, take him at disadvantage.” These few words showed the general’s own estimation of his two lieutenants; both equally brave and chivalrous, but the one uniting with these qualities the circumspection so essential to success in perilous enterprises, in which the other was signally deficient. The future conqueror of Guatemala had to gather wisdom, as usual, from the bitter fruits of his own errors. It was under the training of Cortes that he learned to be a soldier. The general, having concluded his instructions, affectionately embraced his lieutenant, and dismissed him to his quarters.

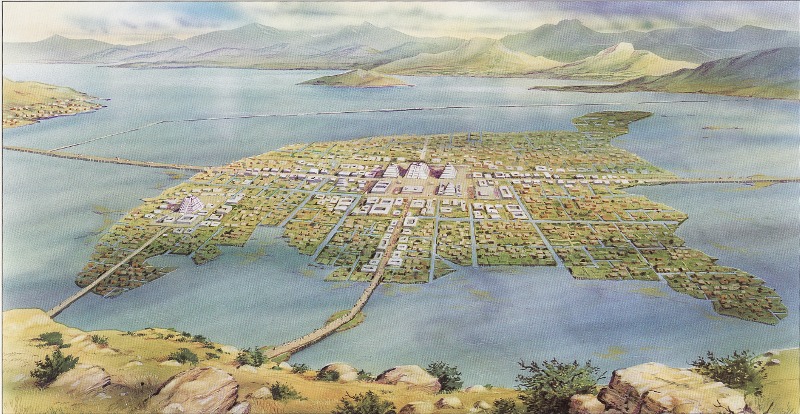

It was late in the afternoon when he reached them; but the sun was still lingering above the western hills, and poured his beams wide over the Valley, lighting up the old towers and temples of Tenochtitlan with a mellow radiance, that little harmonized with the dark scenes of strife in which the city had so lately been involved. The tranquillity of the hour, however, was on a sudden broken by the strange sounds of the great drum in the temple of the war-god, — sounds which recalled the noche triste, with all its terrible images, to the minds of the Spaniards, for that was the only occasion on which they had ever heard them. They intimated some solemn act of religion within the unhallowed precincts of the teocalli; and the soldiers, startled by the mournful vibrations, which might be heard for leagues across the Valley, turned their eyes to the quarter whence they proceeded. They there beheld a long procession winding up the huge sides of the pyramid ; for the camp of Alvarado was pitched scarcely a mile from the city, and objects are distinctly visible at a great distance in the transparent atmosphere of the table-land.

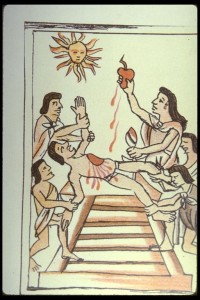

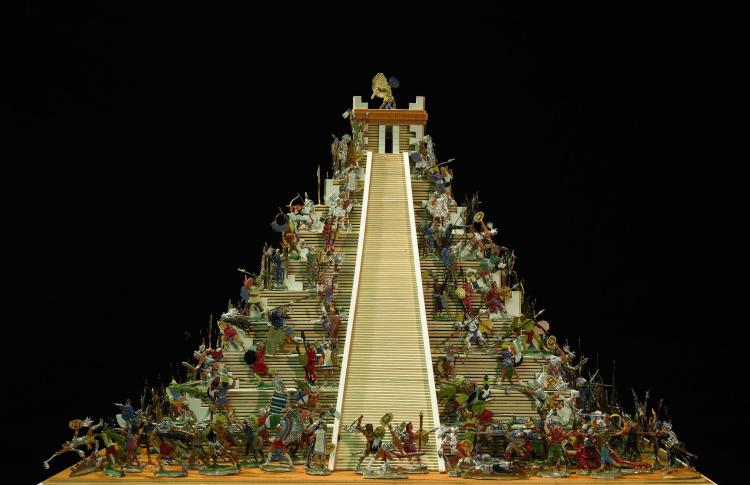

As the long file of priests and warriors reached the flat summit of the teocalli, the Spaniards saw the figures of several men stripped to their waists, some of whom, by the whiteness of their skins, they recognized as their own countrymen. They were the victims for sacrifice. Their heads were gaudily decorated with coronals of plumes, and they carried fans in their hands. They were urged along by blows, and compelled to take part in the dances in honor of the Aztec war-god. The unfortunate captives, then stripped of their sad finery, were stretched, one after another, on the great stone of sacrifice. On its convex surface their breasts were heaved up conveniently for the diabolical purpose of the priestly executioner, who cut asunder the ribs by a strong blow with his sharp razor of itztli, and, thrusting his hand into the wound, tore away the heart, which, hot and reeking, was deposited on the golden censer before the idol. The body of the slaughtered victim was then hurled down the steep stairs of the pyramid, which, it may be remembered, were placed at the same angle of the pile, one flight below another ; and the mutilated remains were gathered up by the savages beneath, who soon prepared with them the cannibal repast which completed the work of abomination!

We may imagine with what sensations the stupefied Spaniards must have gazed on this horrid spectacle, so near that they could almost recognize the persons of their unfortunate friends, see the struggles and writhing of their bodies, hear — or fancy that they heard – their screams of agony! yet so far removed that they could render them no assistance. Their limbs trembled beneath them, as they thought what might one day be their own fate; and the bravest among them, who had hitherto gone to battle as careless and light-hearted as to the banquet or the ball-room, were unable, from this time forward, to encounter their ferocious enemy without a sickening feeling, much akin to fear, coming over them.

Such was not the effect produced by this spectacle on the Mexican forces, gathered at the end of the causeway. Like vultures maddened by the smell of distant carrion, they set up a piercing cry, and, as they shouted that “such should be the fate of all their enemies,” swept along in one fierce torrent over the dike. But the Spaniards were not to be taken by surprise; and, before the barbarian horde had come within their lines, they opened such a deadly fire from their battery of heavy guns, supported by the musketry and cross-bows, that the assailants were compelled to fall back slowly, but fearfully mangled, to their former position.

The five following days passed away in a state of inaction, except, indeed, so far as was necessary to repel the sorties made from time to time by the militia of the capital. The Mexicans, elated with their success, meanwhile, abandoned themselves to jubilee; singing, dancing, and feasting on the mangled relics of their wretched victims. Guatemozin sent several heads of the Spaniards, as well as of the horses, round the country, calling on his old vassals to forsake the banners of the white men, unless they would share  the doom of the enemies of Mexico. The priests now cheered the young monarch and the people with the declaration that the dread Huitzilopochtli, their offended deity, appeased by the sacrifices offered up on his altars, would again take the Aztecs under his protection, and deliver their enemies, before the expiration of eight days, into their hands.

the doom of the enemies of Mexico. The priests now cheered the young monarch and the people with the declaration that the dread Huitzilopochtli, their offended deity, appeased by the sacrifices offered up on his altars, would again take the Aztecs under his protection, and deliver their enemies, before the expiration of eight days, into their hands.

This comfortable prediction, confidently believed by the Mexicans, was thundered in the ears of the besieging army in tones of exultation and defiance. However it may have been contemned by the Spaniards, it had a very different effect on their allies. The latter had begun to be disgusted with a service so full of peril and suffering and already protracted far beyond the usual term of Indian hostilities. They had less confidence than before in the Spaniards. Experience had shown that they were neither invincible nor immortal, and their recent reverses made them even distrust the ability of the Christians to reduce the Aztec metropolis. They recalled to mind the ominous words of Xicotencatl, that “so sacrilegious a war could come to no good for the people of Anahuac.” They felt that their arm was raised against the gods of their country. The prediction of the oracle fell heavy on their hearts. They had little doubt of its fulfilment, and were only eager to turn away the bolt from their own heads by a timely secession from the cause.

They took advantage, therefore, of the friendly cover of night to steal away from their quarters. Company after company deserted in this manner, taking the direction of their respective homes. Those belonging to the great towns of the Valley, whose allegiance was the most recent, were the first to cast it off. Their example was followed by the older confederates, the militia of Cholula, Tepeaca, Tezcuco, and even the faithful Tlascala. There were, it is true, some exceptions to these, and among them Ixtlilxochitl, the young lord of Tezcuco, and Chichemecatl, the valiant Tlascalan chieftain, who, with a few of their immediate followers, still remained true to the banner under which they had enlisted. But their number was insignificant. The Spaniards beheld with dismay the mighty array, on which they relied for support, thus silently melting away before the breath of superstition. Cortes alone maintained a cheerful countenance. He treated the prediction with contempt, as an invention of the priests, and sent his messengers after the retreating squadrons, beseeching them to postpone their departure, or at least to halt on the road, till the time, which would soon elapse, should show the falsehood of the prophecy.

The affairs of the Spaniards at this crisis must be confessed to have worn a gloomy aspect. Deserted by their allies, with their ammunition nearly exhausted, cut off from the customary supplies from the neighborhood, harassed by unintermitting vigils and fatigues, smarting under wounds, of which every man in the army had his share, with an unfriendly country in their rear and a mortal foe in front, they might well be excused for faltering in their enterprise. They found abundant occupation by day in foraging the country, and in maintaining their position on the causeways against the enemy, now made doubly daring by success and by the promises of their priests; while at night their slumbers were disturbed by the beat of the melancholy drum, the sounds of which, booming far over the waters, tolled the knell of their murdered comrades. Night after night fresh victims were led up to the great altar of sacrifice; and, while the city blazed with the illumination of a thousand bonfires on the terraced roofs of the dwellings and in the areas of the temples, the dismal pageant, showing through the fiery glare like the work of the ministers of hell, was distinctly visible from the camp below. One of the last of the sufferers was Guzman, the unfortunate chamberlain of Cortes, who lingered in captivity eighteen days before he met his doom.

Yet in this hour of trial the Spaniards did not falter. Had they faltered, they might have learned a lesson of fortitude from some of their own wives, who continued with them in the camp, and who displayed a heroism, on this occasion, of which history has preserved several examples. One of these, protected by her husband’s armor, would frequently mount guard in his place when he was wearied. Another, hastily putting on a soldier’s escaupilzxA seizing a sword and lance, was seen, on one occasion, to rally their retreating countrymen and lead them back against the enemy. Cortes would have persuaded these Amazonian dames to remain at Tlascala; but they proudly replied, ” It was the duty of Castilian wives not to abandon their husbands in danger, but to share it with them, — and die with them, if necessary.” And well did they do their duty.”

Amidst all the distresses and multiplied embarrassments of their situation, the Spaniards still remained true to their purpose. They relaxed in no degree the severity of the blockade. Their camps still occupied the only avenues to the city; and their batteries, sweeping the long defiles at every fresh assault of the Aztecs, mowed down hundreds of the assailants. Their brigantines still rode on the waters, cutting off the communication with the shore. It is true, indeed, the loss of the auxiliary canoes left a passage open for the occasional introduction of supplies to the capital. But the whole amount of these supplies was small; and its crowded population, while exulting in their temporary advantage and the delusive assurances of their priests, were beginning to sink under the withering grasp of an enemy within, more terrible than the one which lay before their gates.

Thus passed away the eight days prescribed by the oracle ; and the sun which rose upon the ninth beheld the fair city still beset on every side by the inexorable foe. It was a great mistake of the Aztec priests — one not uncommon with false prophets, anxious to produce a startling impression on their followers — to assign so short a term for the fulfilment of their prediction.

Thus passed away the eight days prescribed by the oracle ; and the sun which rose upon the ninth beheld the fair city still beset on every side by the inexorable foe. It was a great mistake of the Aztec priests — one not uncommon with false prophets, anxious to produce a startling impression on their followers — to assign so short a term for the fulfilment of their prediction.

The Tezcucan and Tlascalan chiefs now sent to acquaint their troops with the failure of the prophecy, and to recall them to the Christian camp. The Tlascalans, who had halted on the way, returned, ashamed of their credulity, and with ancient feelings of animosity heightened by the artifice of which they had been the dupes. Their example was followed by many of the other confederates, with the levity natural to a people whose convictions are the result not of reason, but of superstition. In a short time the Spanish general found himself at the head of an auxiliary force which, if not so numerous as before, was more than adequate to all his purposes. He received them with politic benignity; and, while he reminded them that they had been guilty of a great crime in thus abandoning their commander, he was willing to overlook it in consideration of their past services. They must be aware that these services were not necessary to the Spaniards, who had carried on the siege with the same vigor during their absence as when they were present. But he was unwilling that those who had shared the dangers of the war with him should not also partake its triumphs, and be present at the fall of their enemy, which he promised, with a confidence better founded than that of the priests in their prediction, should not be long delayed.

Yet the menaces and machinations of Guatemozin were still not without effect in the distant provinces. Before the full return of the confederates, Cortes received an embassy from Cuernavaca, ten or twelve leagues distant, and another from some friendly towns of the Otomies, still farther off, imploring his protection against their formidable neighbors, who menaced them with hostilities as allies of the Spaniards. As the latter were then situated, they were in a condition to receive succor much more than to give it. Most of the officers were, accordingly, opposed to granting a request compliance with which must still further impair their diminished strength. But Cortes knew the importance, above all, of not betraying his own inability to grant it. “The greater our weakness,” he said, “the greater need have we to cover it under a show of strength.”

He immediately detached Tapia with a body of about a hundred men in one direction, and Sandoval with a somewhat larger force in the other, with orders that their absence should not in any event be prolonged beyond ten days. The two captains executed their commissions promptly and effectually. They each met and defeated his adversary in a pitched battle, laid waste the hostile territories, and returned within the time prescribed. They were soon followed by ambassadors from the conquered places, soliciting the alliance of the Spaniards ; and the affair terminated by an accession of new confederates, and, what was more important, a conviction in the old that the Spaniards were both willing and competent to protect them.

He immediately detached Tapia with a body of about a hundred men in one direction, and Sandoval with a somewhat larger force in the other, with orders that their absence should not in any event be prolonged beyond ten days. The two captains executed their commissions promptly and effectually. They each met and defeated his adversary in a pitched battle, laid waste the hostile territories, and returned within the time prescribed. They were soon followed by ambassadors from the conquered places, soliciting the alliance of the Spaniards ; and the affair terminated by an accession of new confederates, and, what was more important, a conviction in the old that the Spaniards were both willing and competent to protect them.

Fortune, who seldom dispenses her frowns or her favors single-handed, further showed her good will to the Spaniards, at this time, by sending a vessel into Vera Cruz laden with ammunition and military stores. It was part of the fleet destined for the Florida coast by the romantic old knight, Ponce de Leon. The cargo was immediately taken by the authorities of the port, and forwarded, without delay, to the camp, where it arrived most seasonably, as the want of powder, in particular, had begun to be seriously felt. With strength thus renovated, Cortes determined to resume active operations, but on a plan widely differing from that pursued before.

In the former deliberations on the subject, two courses, as we have seen, presented themselves to the general. One was to intrench himself in the heart of the capital and from this point carry on hostilities; the other was the mode of proceeding hitherto followed. Both were open to serious objections, which he hoped would be obviated by the one now adopted. This was to advance no step without securing the entire safety of the army, not only on its immediate retreat, but in its future inroads. Every breach in the causeway, every canal in the streets, was to be filled up in so solid a manner that the work should not be again disturbed. The materials for this were to be furnished by the buildings, every one of which, as the army advanced, whether public or private, hut, temple, or palace, was to be demolished! Not a building in their path was to be spared. They were all indiscriminately to be levelled, until, in the Conqueror’s own language, “the water should be converted into dry land,” and a smooth and open ground be afforded for the manoeuvres of the cavalry and artillery!

Cortes came to this terrible determination with great difficulty. He sincerely desired to spare the city, “the most beautiful thing in the world,” as he enthusiastically styles it, and which would have formed the most glorious trophy of his conquest. But in a place where every house was a fortress and every street was cut up by canals so embarrassing to his movements, experience proved it was vain to think of doing so and becoming master of it. There was as little hope of a peaceful accommodation with the Aztecs, who, so far from being broken by all they had hitherto endured, and the long perspective of future woes, showed a spirit as haughty and implacable as ever.

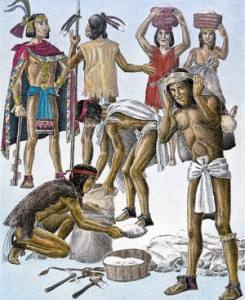

The general’s intentions were learned by the Indian allies with unbounded satisfaction; and they answered his call for aid by thousands of pioneers, armed with their coas, or hoes of the country, all testifying the greatest alacrity in helping on the work of destruction.

In a short time the breaches in the great causeways were filled up so effectually that they were never again molested. Cortes himself set the example by carrying stones and timber with his own hands. The buildings in the suburbs were then thoroughly levelled, the canals were filled up with the rubbish, and a wide space around the city was thrown open to the manoeuvres of the cavalry, who swept over it free and unresisted. The Mexicans did not look with indifference on these preparations to lay waste their town and leave them bare and unprotected against the enemy. They made incessant efforts to impede the labors of the besiegers; but the latter, under cover of their guns, which kept up an unintermitting fire, still advanced in the work of desolation.”

The gleam of fortune which had so lately broken out on the Mexicans again disappeared; and the dark mist, after having been raised for a moment, settled on the doomed capital more heavily than before. Famine, with all her hideous train of woes, was making rapid strides among its accumulated population. The stores provided for the siege were exhausted. The casual supply of human victims, or that obtained by some straggling pirogue from the neighboring shores, was too inconsiderable to be widely felt.” Some forced a scanty sustenance from a mucilaginous substance gathered in small quantities on the surface of the lake and canals. Others appeased the cravings of appetite by devouring rats, lizards, and the like loathsome reptiles, which had not yet deserted the starving city. Its days seemed to be already numbered. But the page of history has many an example to show that there are no limits to the endurance of which humanity is capable, when animated by hatred and despair.

The gleam of fortune which had so lately broken out on the Mexicans again disappeared; and the dark mist, after having been raised for a moment, settled on the doomed capital more heavily than before. Famine, with all her hideous train of woes, was making rapid strides among its accumulated population. The stores provided for the siege were exhausted. The casual supply of human victims, or that obtained by some straggling pirogue from the neighboring shores, was too inconsiderable to be widely felt.” Some forced a scanty sustenance from a mucilaginous substance gathered in small quantities on the surface of the lake and canals. Others appeased the cravings of appetite by devouring rats, lizards, and the like loathsome reptiles, which had not yet deserted the starving city. Its days seemed to be already numbered. But the page of history has many an example to show that there are no limits to the endurance of which humanity is capable, when animated by hatred and despair.

With the sword thus suspended over it, the Spanish commander, desirous to make one more effort to save the capital, persuaded three Aztec nobles, taken in one of the late actions, to bear a message from him to Guatemozin; though they undertook it with reluctance, for fear of the consequences to themselves. Cortes told the emperor that all had now been done that brave men could do in defence of their country.

There remained no hope, no chance of escape, for the Mexicans. Their provisions were exhausted; their communications were cut off; their vassals had deserted them ; even their gods had betrayed them. They stood alone, with the nations of Anahuac banded against them. There was no hope but in immediate surrender. He besought the young monarch to take compassion on his brave subjects, who were daily perishing before his eyes ; and on the fair city, whose stately buildings were fast crumbling into ruins. ” Return to the allegiance,” he concludes, “which you once proffered to the sovereign of Castile. The past shall be forgotten. The persons and property, in short, all the rights, of the Aztecs shall be respected. You shall be confirmed in your authority, and Spain will once more take your city under her protection.” The eye of the young monarch kindled, and his dark cheek flushed with sudden anger, as he listened to proposals so humiliating. But, though his bosom glowed with the fiery temper of the Indian, he had the qualities of a “gentle cavalier,” says one of his enemies, who knew him well. He did no harm to the envoys; but, after the heat of the moment had passed off, he gave the matter a calm consideration, and called a council of his wise men and warriors to deliberate upon it. Some were for accepting the proposals, as offering the only chance of preservation. But the priests took a different view of the matter. They knew that the ruin of their own order must follow the triumph of Christianity. “Peace was good,” they said, “but not with the white men.” They reminded Guatemozin of the fate of his uncle Montezuma, and the requital he had met with for all his hospitality; of the seizure and imprisonment of Cacama, the cacique of Tezcuco ; of the massacre of the nobles by Alvarado; of the insatiable avarice of the invaders, which had stripped the country of its treasures; of their profanation of the temples ; of the injuries and insults which they had heaped without measure on the people and their religion. “Better,” they said, “to trust in the promises of their own gods, who had so long watched over the nation. Better, if need be, give up our lives at once for our country, than drag them out in slavery and suffering among the false strangers.”

The eloquence of the priests, artfully touching the various wrongs of his people, roused the hot blood of Guatemozin. “Since it is so,” he abruptly exclaimed, “let us think only of supplying the wants of the people. Let no man, henceforth, who values his life, talk of surrender. We can at least die like warriors.”

The Spaniards waited two days for the answer to their embassy. At length it came, in a general sortie of the Mexicans, who, pouring through every gate of the capital, like a river that has burst its banks, swept on, wave upon wave, to the very intrenchments of the besiegers, threatening to overwhelm them by their numbers. Fortunately, the position of the latter on the dikes secured their flanks, and the narrowness of the defile gave their small battery of guns all the advantages of a larger one. The fire of artillery and musketry blazed without intermission along the several causeways, belching forth volumes of sulphurous smoke, that, rolling heavily over the waters, settled dark around the Indian city and hid it from the surrounding country. The brigantines thundered, at the same time, on the flanks of the columns, which, after some ineffectual efforts to maintain themselves, rolled back in wild confusion, till their impotent fury died away in sullen murmurs within the capital.

Cortes now steadily pursued the plan he had laid down for the devastation of the city. Day after day the several armies entered by their respective quarters, Sandoval probably directing his operations against the northeastern district. The buildings, made of the porous tetzontli, though generally low, were so massy and extensive, and the canals were so numerous, that their progress was necessarily slow. They, however, gathered fresh accessions of strength every day from the numbers who flocked to the camp from the surrounding country, and who joined in the work of destruction with a hearty good will which showed their eagerness to break the detested yoke of the Aztecs. The latter raged with impotent anger as they beheld their lordly edifices, their temples, all they had been accustomed to venerate, thus ruthlessly swept away; their canals, constructed with so much labor and what to them seemed science, filled up with rubbish; their flourishing city, in short, turned into a desert, over which the insulting foe now rode  triumphant. They heaped many a taunt on the Indian allies. ” Go on,” they said, bitterly: “the more you destroy, the more you will have to build up again hereafter. If we conquer, you shall build for us; and if your white friends conquer, they will make you do as much for them.” The event justified the prediction.

triumphant. They heaped many a taunt on the Indian allies. ” Go on,” they said, bitterly: “the more you destroy, the more you will have to build up again hereafter. If we conquer, you shall build for us; and if your white friends conquer, they will make you do as much for them.” The event justified the prediction.

In their rage they rushed blindly on the corps which covered the Indian pioneers. But they were as often driven back by the impetuous charge of the cavalry, or received on the long pikes of Chinantla, which did good service to the besiegers in their operations. At the close of day, however, when the Spaniards drew off their forces, taking care to send the multitudinous host of confederates first from the ground, the Mexicans usually rallied for a more formidable attack. Then they poured out from every lane and by-way, like so many mountain streams, sweeping over the broad level cleared by the enemy, and falling impetuously on their flanks and rear. At such times they inflicted considerable loss in their turn, till an ambush, which Cortes laid for them among the buildings adjoining the great temple, did them so much mischief that they were compelled to act with more reserve.

At times the war displayed something of a chivalrous character, in the personal rencontres of the combatants. Challenges passed between them, and especially between the native warriors. These combats were usually conducted on the azoteas, whose broad and level surface afforded a good field of fight. On one occasion, a Mexican of powerful frame, brandishing a sword and buckler which he had won from the Christians, defied his enemies to meet him in single fight. A young page of Cortes’, named Nunez, obtained his master’s permission to accept the vaunting challenge of the Aztec, and, springing on the azotea, succeeded, after a hard struggle, in discomfiting his antagonist, who fought at a disadvantage with weapons in which he was unpractised, and, running him through the body, brought off his spoils in triumph and laid them at the general’s feet.

The division of Cortes had now worked its way as far north as the great street of Tacuba, which opened a communication with Alvarado’s camp, and near which stood the palace of Guatemozin. It was a spacious stone pile, that might well be called a fortress. Though deserted by its royal master, it was held by a strong body of Aztecs, who made a temporary defence, but of little avail against the battering enginery of the besiegers. It was soon set on fire, and its crumbling walls were levelled in the dust, like those other stately edifices of the capital, the boast and admiration of the Aztecs, and some of the fairest fruits of their civilization.” It was a sad thing to witness their destruction,” exclaims Cortes; “but it was part of our plan of operations, and we had no alternative.”

These operations had consumed several weeks, so that it was now drawing towards the latter part of July. During this time the blockade had been maintained with the utmost rigor, and the wretched inhabitants were suffering all the extremities of famine. Some few stragglers were taken, from time to time, in the neighborhood of the Christian camp, whither they had wandered in search of food. They were kindly treated, by command of Cortes, who was in hopes to induce others to follow their example, and thus to afford a means of conciliating the inhabitants, which might open the way to their submission. But few were found willing to leave the shelter of the capital, and they preferred to take their chance with their suffering countrymen rather than trust themselves to the mercies of the besiegers.

From these few stragglers, however, the Spaniards heard a dismal tale of woe respecting the crowded population in the interior of the city. All the ordinary means of sustenance had long .since failed, and they now supported life as they could, by means of such roots as they could dig from the earth, by gnawing the bark of trees, by feeding on the grass, — on anything, in short, however loathsome, that could allay the craving of appetite. Their only drink was the brackish water of the soil saturated with the salt lake.” Under this unwholesome diet, and the diseases engendered by it, the population was gradually wasting away. Men sickened and died every day, in all the excruciating torments produced by hunger, and the wan and emaciated survivors seemed only to be waiting for their time.

The Spaniards had visible confirmation of all this as they penetrated deeper into the city and approached the district of Tlatelolco, now occupied by the besieged. They found the ground turned up in quest of roots and weeds, the trees stripped of their green stems, their foliage, and their bark. Troops of famished Indians flitted in the distance, gliding like ghosts among the scenes of their former residence. Dead bodies lay unburied in the streets and court -yards, or filled up the canals. It was a sure sign of the extremity of the Aztecs; for they held the burial of the dead as a solemn and imperative duty. In the early part of the siege they had religiously attended to it. In its later stages they were still careful to withdraw the dead from the public eye, by bringing their remains within the houses. But the number of these, and their own sufferings, had now so fearfully increased that they had grown indifferent to this, and they suffered their friends and their kinsmen to lie and moulder on the spot where they drew their last breath!

As the invaders entered the dwellings, a more appalling spectacle presented itself; — the floors covered with the prostrate forms of the miserable inmates, some in the agonies of death, others festering in their corruption; men, women, and children inhaling the poisonous atmosphere, and mingled promiscuously together; mothers with their infants in their arms perishing of hunger before their eyes, while they were unable to afford them the nourishment of nature; men crippled by their wounds, with their bodies frightfully mangled, vainly attempting to crawl away, as the enemy entered. Yet even in this state they scorned to ask for mercy, and glared on the invaders with the sullen ferocity of the wounded tiger that the huntsmen have tracked to his forest cave. The Spanish commander issued strict orders that mercy should be shown to these poor and disabled victims. But the Indian allies made no distinction. An Aztec, under whatever circumstances, was an enemy ; and, with hideous shouts of triumph, they pulled down the burning buildings on their heads, consuming the living and the dead in one common funeral pile!

As the invaders entered the dwellings, a more appalling spectacle presented itself; — the floors covered with the prostrate forms of the miserable inmates, some in the agonies of death, others festering in their corruption; men, women, and children inhaling the poisonous atmosphere, and mingled promiscuously together; mothers with their infants in their arms perishing of hunger before their eyes, while they were unable to afford them the nourishment of nature; men crippled by their wounds, with their bodies frightfully mangled, vainly attempting to crawl away, as the enemy entered. Yet even in this state they scorned to ask for mercy, and glared on the invaders with the sullen ferocity of the wounded tiger that the huntsmen have tracked to his forest cave. The Spanish commander issued strict orders that mercy should be shown to these poor and disabled victims. But the Indian allies made no distinction. An Aztec, under whatever circumstances, was an enemy ; and, with hideous shouts of triumph, they pulled down the burning buildings on their heads, consuming the living and the dead in one common funeral pile!

Yet the sufferings of the Aztecs, terrible as they were, did not incline them to submission. There were many, indeed, who, from greater strength of constitution, or from the more favorable circumstances in which they were placed, still showed all their wonted energy of body and mind, and maintained the same undaunted and resolute demeanor as before. They fiercely rejected all the overtures of Cortes, declaring they would rather die than surrender, and adding, with a bitter tone of exultation, that the invaders would be at least disappointed in their expectations of treasure, for it was buried where they could never find it!

The women, it is said, shared in this desperate — it should rather be called heroic — spirit. They were indefatigable in nursing the sick and dressing their wounds; they aided the warriors in battle, by supplying them with the Indian ammunition of stones and arrows, prepared their slings, strung their bows, and displayed, in short, all the constancy and courage shown by the noble maidens of Saragossa in our day, and by those of Carthage in the days of antiquity.

Cortes had now entered one of the great avenues leading to the market-place of Tlatelolco, the quarter towards which the movements of Alvarado were also directed. A single canal only lay in his way; but this was of great width and stoutly defended by the Mexican archery. At this crisis, the army one evening, while in their intrenchments on the causeway, were surprised by an uncommon light that arose from the huge teocalli in that part of the city which, being at the north, was the most distant from their own position. This temple, dedicated to the dread war-god, was inferior only to the pyramid in the great square; and on it the Spaniards had more than once seen their unhappy countrymen led to slaughter. They now supposed that the enemy were employed in some of their diabolical ceremonies, — when the flame, mounting higher and higher, showed that the sanctuaries themselves were on fire. A shout of exultation at the sight broke forth from the assembled soldiers, as they assured one another that their countrymen under Alvarado had got possession of the building.

It was indeed true. That gallant officer, whose position on the western causeway placed him near the district of Tlatelolco, had obeyed his commander’s instructions to the letter, razing every building to the ground in his progress, and filling up the ditches with their ruins. He at length found himself before the great teocalli in the neighborhood of the market. He ordered a company, under a cavalier named Gutierre de Badajoz, to storm the place, which was defended by a body of warriors, mingled with priests, still more wild and ferocious than the soldiery. The garrison, rushing down the winding terraces, fell on, the assailants with such fury as compelled them to retreat in confusion and with some loss. Alvarado ordered another detachment to their support. This last was engaged, at the moment, with a body of Aztecs, who hung on its rear as it wound up the galleries of the teocalli. Thus hemmed in between two enemies, above and below, the position of the Spaniards was critical. With sword and buckler, they plunged desperately on the ascending Mexicans, and drove them into the courtyard below, where Alvarado plied them with such lively volleys of musketry as soon threw them into disorder and compelled them to abandon the ground. Being thus rid of annoyance in the rear, the Spaniards returned to the charge. They drove the enemy up the heights of the pyramid, and, reaching the broad summit, a fierce encounter followed in mid-air, — such an encounter as takes place where death is the certain consequence of defeat. It ended, as usual, in the discomfiture of the Aztecs, who were either slaughtered on the spot still wet with the blood of their own victims, or pitched headlong down the sides of the pyramid.

It was indeed true. That gallant officer, whose position on the western causeway placed him near the district of Tlatelolco, had obeyed his commander’s instructions to the letter, razing every building to the ground in his progress, and filling up the ditches with their ruins. He at length found himself before the great teocalli in the neighborhood of the market. He ordered a company, under a cavalier named Gutierre de Badajoz, to storm the place, which was defended by a body of warriors, mingled with priests, still more wild and ferocious than the soldiery. The garrison, rushing down the winding terraces, fell on, the assailants with such fury as compelled them to retreat in confusion and with some loss. Alvarado ordered another detachment to their support. This last was engaged, at the moment, with a body of Aztecs, who hung on its rear as it wound up the galleries of the teocalli. Thus hemmed in between two enemies, above and below, the position of the Spaniards was critical. With sword and buckler, they plunged desperately on the ascending Mexicans, and drove them into the courtyard below, where Alvarado plied them with such lively volleys of musketry as soon threw them into disorder and compelled them to abandon the ground. Being thus rid of annoyance in the rear, the Spaniards returned to the charge. They drove the enemy up the heights of the pyramid, and, reaching the broad summit, a fierce encounter followed in mid-air, — such an encounter as takes place where death is the certain consequence of defeat. It ended, as usual, in the discomfiture of the Aztecs, who were either slaughtered on the spot still wet with the blood of their own victims, or pitched headlong down the sides of the pyramid.

The area was covered with the various symbols of the barbarous worship of the country, and with two lofty sanctuaries, before whose grinning idols were displayed the heads of several Christian captives who had been immolated on their altars. Although overgrown by their long, matted hair and bushy beards, the Spaniards could recognize, in the livid countenances, their comrades who had fallen into the hands of the enemy. Tears fell from their eyes as they gazed on the melancholy spectacle and thought of the hideous death which their countrymen had suffered. They removed the sad relics with decent care, and after the Conquest deposited them in consecrated ground, on a spot since covered by the Church of the Martyrs.

They completed their work by firing the sanctuaries, that the place might be no more polluted by these abominable rites. The flame crept slowly up the lofty pinnacles, in which stone was mingled with wood, till at length, bursting into one bright blaze, it shot up its spiral volume to such a height that it was seen from the most distant quarters of the Valley. It was this which had been hailed by the soldiery of Cortes, and it served as the beacon-light to both friend and foe, intimating the progress of the Christian arms.

They completed their work by firing the sanctuaries, that the place might be no more polluted by these abominable rites. The flame crept slowly up the lofty pinnacles, in which stone was mingled with wood, till at length, bursting into one bright blaze, it shot up its spiral volume to such a height that it was seen from the most distant quarters of the Valley. It was this which had been hailed by the soldiery of Cortes, and it served as the beacon-light to both friend and foe, intimating the progress of the Christian arms.

The commander-in-chief and his division, animated by the spectacle, made, in their entrance on the following day, more determined efforts to place themselves alongside of their companions under Alvarado. The broad canal, above noticed as the only impediment now lying in his way, was to be traversed; and on the farther side the emaciated figures of the Aztec warriors were gathered in numbers to dispute the passage, like the gloomy shades that wander — as ancient poets tell us — on the banks of the infernal river. They poured down, however, a storm of missiles, which were no shades, on the heads of the Indian laborers while occupied with filling up the wide gap with the ruins of the surrounding buildings. Still they toiled on in defiance of the arrowy shower, fresh numbers taking the place of those who fell. And when at length the work was completed, the cavalry rode over the rough plain at full charge against the enemy, followed by the deep array of spearmen, who bore down all opposition with their invincible phalanx.

The Spaniards now found themselves on the same ground with Alvarado’s division. Soon afterwards, that chief, attended by several of his staff, rode into their lines, and cordially embraced his countrymen and companions in arms, for the first time since the beginning of the siege. They were now in the neighborhood of the market. Cortes, taking with him a few of his cavaliers, galloped into it. It was a vast enclosure, as the reader has already seen, covering many an acre. Its dimensions were suited to the immense multitudes who gathered there from all parts of the Valley in the flourishing days of the Aztec monarchy. It was surrounded by porticoes and pavilions for the accommodation of the artisans and traders who there displayed their various fabrics and articles of merchandise. The flat roofs of the piazzas were now covered with crowds of men and women, who gazed in silent dismay on the steel-clad horsemen, that profaned these precincts with their presence for the first time since their expulsion from the capital. The multitude, composed for the most part, probably, of unarmed citizens, seemed taken by surprise ; at least, they made no show of resistance; and the general, after leisurely viewing the ground, was permitted to ride back unmolested to the army.

On arriving there, he ascended the teocalli, from which the standard of Castile, supplanting the memorials of Aztec superstition, was now triumphantly floating. The Conqueror, as he strode among the smoking embers on the summit, calmly surveyed the scene of desolation below. The palaces, the temples, the busy marts of industry and trade, the glittering canals, covered with their rich freights from the surrounding country, the royal pomp of groves and gardens, all the splendors of the imperial city, the capital of the Western World, forever gone, — and in their place a barren wilderness ! How different the spectacle which the year before had met his eye, as it wandered over the same scenes from the heights of the neighboring teocalli, with Montezuma at his side! Seven eighths of the city were laid in ruins, with the occasional exception, perhaps, of some colossal temple which it would have required too much time to demolish. The remaining eighth, comprehending the district of Tlatelolco, was all that now remained to the Aztecs, whose population — still large after all its losses — was crowded into a compass that would hardly have afforded accommodations for a third of their numbers. It was the quarter lying between the great northern and western causeways, and is recognized in the modern capital as the Barrio de San Jago and its vicinity. It was the favorite residence of the Indians after the Conquest, though at the present day thinly covered with humble dwellings, forming the straggling suburbs, as it were, of the metropolis. Yet it still affords some faint vestiges of what it was in its prouder days; and the curious antiquary, and occasionally the laborer, as he turns up the soil, encounters a glittering fragment of obsidian, or the mouldering head of a lance or arrow, or some other warlike relic, attesting that on this spot the retreating Aztecs made their last stand for the independence of their country.

On the day following, Cortes, at the head of his battalions, made a second entry into the great tianguez. But this time the Mexicans were better prepared for his coming. They were assembled in considerable force in the spacious square. A sharp encounter followed ; but it was short. Their strength was not equal to their spirit, and they melted away before the rolling fire of musketry, and left the Spaniards masters of the enclosure.

On the day following, Cortes, at the head of his battalions, made a second entry into the great tianguez. But this time the Mexicans were better prepared for his coming. They were assembled in considerable force in the spacious square. A sharp encounter followed ; but it was short. Their strength was not equal to their spirit, and they melted away before the rolling fire of musketry, and left the Spaniards masters of the enclosure.

The first act was to set fire to some temples, of no great size, within the market-place, or more probably on its borders. As the flames ascended, the Aztecs, horror-struck, broke forth into piteous lamentations at the destruction of the deities on whom they relied for protection.

The general’s next step was at the suggestion of a soldier named Sotelo, a man who had served under the Great Captain in the Italian wars, where he professed to have gathered knowledge of the science of engineering, as it was then practised. He offered his services to construct a sort of catapult, a machine for discharging stones of great size, which might take the place of the regular battering-train in demolishing the buildings. As the ammunition, notwithstanding the liberal supplies which from time to time had found their way into the camp, now began to fail, Cortes eagerly acceded to a proposal so well suited to his exigences. Timber and stone were furnished, and a number of hands were employed, under the direction of the self-styled engineer, in constructing the ponderous apparatus, which was erected on a solid platform of masonry, thirty paces square and seven or eight feet high, that covered the centre of the market-place. This was a work of the Aztec princes, and was used as a scaffolding on which mountebanks and jugglers might exhibit their marvelous feats for the amusement of the populace, who took great delight in these performances.

The erection of the machine consumed several days, during which hostilities were suspended, while the artisans were protected from interruption by a strong corps of infantry. At length the work was completed; and the besieged, who with silent awe had beheld from the neighboring azoteas the progress of the mysterious engine which was to lay the remainder of their capital in ruins, now looked with terror for its operation. A stone of huge size was deposited on the timber. The machinery was set in motion; and the rocky fragment was discharged with a tremendous force from the catapult. But, instead of taking the direction of the Aztec buildings, it rose high and perpendicularly into the air, and, descending whence it sprung, broke the ill-omened machine into splinters! It was a total failure. The Aztecs were released from their apprehensions, and the soldiery made many a merry jest on the catastrophe, somewhat at the expense of their commander, who testified no little vexation at the disappointment, and still more at his own credulity.

There was no occasion to resort to artificial means to precipitate the ruin of the Aztecs. It was accelerated every hour by causes more potent than those arising from mere human agency. There they were, — pent up in their close and suffocating quarters, nobles, commoners, and slaves, men, women, and children, some in houses, more frequently in hovels, — for this part of the city was not the best, — others in the open air in canoes, or in the streets, shivering in the cold rains of night, and scorched by the burning heat of day. An old chronicler mentions the fact of two women of rank remaining three days and nights up to their necks in the water among the reeds, with only a handful of maize for their support. The ordinary means of sustaining life were long since gone. They wandered about in search of anything, however unwholesome or revolting, that might mitigate the fierce gnawings of hunger. Some hunted for insects and worms on the borders of the lake, or gathered the salt weeds and moss from its bottom, while at times they might be seen casting a wistful look at the green hills beyond, which many of them had left to share the fate of their brethren in the capital.

To their credit, it is said by the Spanish writers that they were not driven, in their extremity, to violate the laws of nature by feeding on one another. But, unhappily, this is contradicted by the Indian authorities, who state that many a mother, in her agony, devoured the offspring which she had no longer the means of supporting. This is recorded of more than one siege in history; and it is the more probable here, where the sensibilities must have been blunted by familiarity with the brutal practices of the national superstition.

To their credit, it is said by the Spanish writers that they were not driven, in their extremity, to violate the laws of nature by feeding on one another. But, unhappily, this is contradicted by the Indian authorities, who state that many a mother, in her agony, devoured the offspring which she had no longer the means of supporting. This is recorded of more than one siege in history; and it is the more probable here, where the sensibilities must have been blunted by familiarity with the brutal practices of the national superstition.

But all was not sufficient, and hundreds of famished wretches died every day from extremity of suffering. Some dragged themselves into the houses, and drew their last breath alone and in silence. Others sank down in the public streets. Wherever they died, there they were left. There was no one to bury or to remove them. Familiarity with the spectacle made men indifferent to it. They looked on in dumb despair, waiting for their own turn. There was no complaint, no lamentation, but deep, unutterable woe.

If in other quarters of the town the corpses might be seen scattered over the streets, here they were gathered in heaps. “They lay so thick,” says Bernal Diaz, “that one could not tread except among the bodies.” “A man could not set his foot down,” says Cortes, yet more strongly, “unless on the corpse of an Indian.” They were piled one upon another, the living mingled with the dead. They stretched themselves on the bodies of their friends, and lay down to sleep there. Death was everywhere. The city was a vast charnel-house, in which all was hastening to decay and decomposition. A poisonous steam arose from the mass of putrefaction, under the action of alternate rain and heat, which so tainted the whole atmosphere that the Spaniards, including the general himself, in their brief visits to the quarter, were made ill by it, and it bred a pestilence that swept off even greater numbers than the famine.

Men’s minds were unsettled by these strange and accumulated horrors. They resorted to all the superstitious rites prescribed by their religion, to stay the pestilence. They called on their priests to invoke the gods in their behalf. But the oracles were dumb, or gave only gloomy responses. Their deities had deserted them, and in their place they saw signs of celestial wrath, telling of still greater woes in reserve. Many, after the siege, declared that, among other prodigies, they beheld a stream of light, of a blood red color, coming from the north in the direction of Tepejacac, with a rushing noise like that of a whirlwind, which swept round the district of Tlatelolco, darting out sparkles and flakes of fire, till it shot far into the centre of the lake! In the disordered state of their nerves, a mysterious fear took possession of their senses. Prodigies were of familiar occurrence, and the most familiar phenomena of nature were converted into prodigies. 9 Stunned by their calamities, reason was bewildered, and they became the sport of the wildest and most superstitious fancies.

In the midst of these awful scenes, the young emperor of the Aztecs remained, according to all accounts, calm and courageous. With his fair capital laid in ruins before his eyes, his nobles and faithful subjects dying around him, his territory rent away, foot by foot, till scarce enough remained for him to stand on, he rejected every invitation to capitulate, and showed the same indomitable spirit as at the commencement of the siege. When Cortes, in the hope that the extremities of the besieged would incline them to listen to an accommodation, persuaded a noble prisoner to bear to Guatemozin his proposals to that effect, the fierce young monarch, according to the general, ordered him at once to be sacrificed. It is a Spaniard, we must remember, who tells the story.

In the midst of these awful scenes, the young emperor of the Aztecs remained, according to all accounts, calm and courageous. With his fair capital laid in ruins before his eyes, his nobles and faithful subjects dying around him, his territory rent away, foot by foot, till scarce enough remained for him to stand on, he rejected every invitation to capitulate, and showed the same indomitable spirit as at the commencement of the siege. When Cortes, in the hope that the extremities of the besieged would incline them to listen to an accommodation, persuaded a noble prisoner to bear to Guatemozin his proposals to that effect, the fierce young monarch, according to the general, ordered him at once to be sacrificed. It is a Spaniard, we must remember, who tells the story.

Cortes, who had suspended hostilities for several days, in the vain hope that the distresses of the Mexicans would bend them to submission, now determined to drive them to it by a general assault. Cooped up as they were within a narrow quarter of the city, their position favored such an attempt. He commanded Alvarado to hold himself in readiness, and directed Sandoval — who, besides the causeway, had charge of the fleet, which lay off the Tlatelolcan district — to support the attack by a cannonade on the houses near the water. He then led his forces into the city, or rather across the horrid waste that now encircled it.

On entering the Indian precincts, he was met by several of the chiefs, who, stretching forth their emaciated arms, exclaimed, “You are the children of the Sun. But the Sun is swift in his course. Why are you, then, so tardy? Why do you delay so long to put an end to our miseries ? Rather kill us at once, that we may go to our god Huitzilopochtli, who waits for us in heaven to give us rest from our sufferings!”

Cortes was moved by their piteous appeal, and answered that he desired not their death, but their submission.” Why does your master refuse to treat with me,” he said, “when a single hour will suffice for me to crush him and all his people?” He then urged them to request Guatemozin to confer with him, with the assurance that he might do it in safety, as his person should not be molested.

The nobles, after some persuasion, undertook the mission; and it was received by the young monarch in a manner which showed — if the anecdote before related of him be true — that misfortune had at length asserted some power over his haughty spirit. He consented to the interview, though not to have it take place on that day, but the following, in the great square of Tlatelolco. Cortes, well satisfied, immediately withdrew from the city and resumed his position on the causeway.

The next morning he presented himself at the place appointed, having previously stationed Alvarado there with a strong corps of infantry, to guard against treachery. The stone platform in the centre of the square was covered with mats and carpets, and a banquet was prepared to refresh the famished monarch and his nobles. Having made these arrangements, he awaited the hour of the interview.

But Guatemozin, instead of appearing himself, sent his nobles, the same who had brought to him the general’s invitation, and who now excused their master’s absence on the plea of illness. Cortes, though disappointed, gave a courteous reception to the envoys, considering that it might still afford the means of opening a communication with the emperor. He persuaded them, without much entreaty, to partake of the good cheer spread before them, which they did with a voracity that told how severe had been their abstinence. He then dismissed them with a seasonable supply of provisions for their master, pressing him to consent to an interview, without which it was impossible their differences could be adjusted.

The Indian envoys returned in a short time, bearing with them a present of fine cotton fabrics, of no great value, from Guatemozin, who still declined to meet the Spanish general. Cortes, though deeply chagrined, was unwilling to give up the point.” He will surely come,” he said to the envoys, “when he sees that I suffer you to go and come unharmed, you who have been my steady enemies, no less than himself, throughout the war. He has nothing to fear from me.” He again parted with them, promising to receive their answer the following day.

On the next morning the Aztec chiefs, entering the Christian quarters, announced to Cortes that Guatemozin would confer with him at noon in the marketplace. The general was punctual at the hour; but without success. Neither monarch nor ministers appeared there. It was plain that the Indian prince did not care to trust the promises of his enemy. A thought of Montezuma may have passed across his mind. After he had waited three hours, the general’s patience was exhausted, and, as he learned that the Mexicans were busy in preparations for defence, he made immediate dispositions for the assault.

The confederates had been left without the walls; for he did not care to bring them within sight of the quarry before he was ready to slip the leash. He now ordered them to join him, and, supported by Alvarado’s division, marched at once into the enemy’s quarters. He found them prepared to receive him. Their most able-bodied warriors were thrown into the van, covering their feeble and crippled comrades. Women were seen occasionally mingling in the ranks, and, as well as children, thronged the azoteas, where, with famine-stricken visages and haggard eyes, they scowled defiance and hatred on their invaders.

As the Spaniards advanced, the Mexicans set up a fierce war-cry, and sent off clouds of arrows with their accustomed spirit, while the women and boys rained down darts and stones from their elevated position on the terraces. But the missiles were sent by  hands too feeble to do much damage ; and, when the squadrons closed, the loss of strength became still more sensible in the Aztecs. Their blows fell feebly and with doubtful aim, though some, it is true, of stronger constitution, or gathering strength from despair, maintained to the last a desperate fight.

hands too feeble to do much damage ; and, when the squadrons closed, the loss of strength became still more sensible in the Aztecs. Their blows fell feebly and with doubtful aim, though some, it is true, of stronger constitution, or gathering strength from despair, maintained to the last a desperate fight.

The arquebusiers now poured in a deadly fire. The brigantines replied by successive volleys, in the opposite quarter. The besieged, hemmed in, like deer surrounded by the huntsmen, were brought down on every side. The carnage was horrible. The ground was heaped up with slain, until the maddened combatants were obliged to climb over the human mounds to get at one another. The miry soil was saturated with blood, which ran off like water and dyed the canals themselves with crimson.’ All was uproar and terrible confusion. The hideous yells of the barbarians, the oaths and execrations of the Spaniards, the cries of the wounded, the shrieks of women and children, the heavy blows of the Conquerors, the death-struggle of their victims, the rapid, reverberating echoes of musketry, the hissing of innumerable missiles, the crash and crackling of blazing buildings, crushing hundreds in their ruins, the blinding volumes of dust and sulphurous smoke shrouding all in their gloomy canopy, made a scene appalling even to the soldiers of Cortes, steeled as they were by many a rough passage of war, and by long familiarity with blood and violence. “The piteous cries of the women and children, in particular,” says the general, “were enough to break one’s heart.” He commanded that they should be spared, and that all who asked it should receive quarter. He particularly urged this on the confederates, and placed Spaniards among them to restrain their violence. But he had set an engine in motion too terrible to be controlled. It were as easy to curb the hurricane in its fury, as the passions of an infuriated horde of savages. “Never did I see so pitiless a race,” he exclaims, “or anything wearing the form of man so destitute of humanity.” They made no distinction of sex or age, and in this hour of vengeance seemed to be requiting the hoarded wrongs of a century. At length, sated with slaughter, the Spanish commander sounded a retreat. It was full time, if, according to his own statement, — we may hope it is an exaggeration, — forty thousand souls had perished! Yet their fate was to be envied, in comparison with that of those who survived.

Through the long night which followed, no movement was perceptible in the Aztec quarter. No light was seen there, no sound was heard, save the low moaning of some wounded or dying wretch, writhing in his agony. All was dark and silent, — the darkness of the grave. The last blow seemed to have completely stunned them. They had parted with hope, and sat in sullen despair, like men waiting in silence the stroke of the executioner. Yet, for all this, they showed no disposition to submit. Every new injury had sunk deeper into their souls, and filled them with a deeper hatred of their enemy. Fortune, friends, kindred, home, — all were gone. They were content to throw away life itself, now that they had nothing more to live for.