Brenton Sanderson

Occidental Observer

July 28, 2015

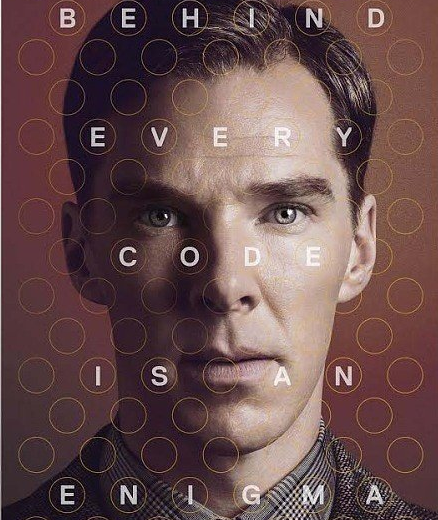

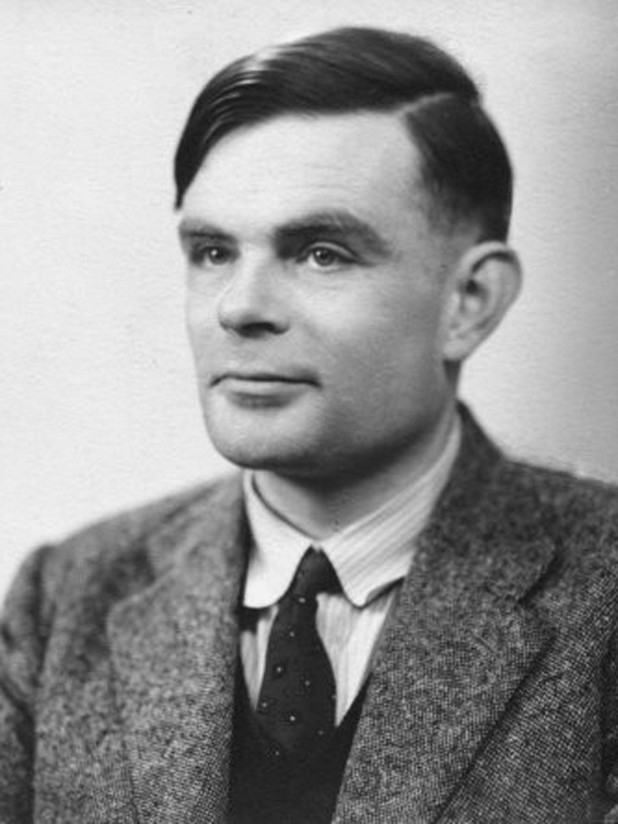

The Imitation Game is a 2014 historical thriller film based on the biography Alan Turing: The Enigma by the mathematician and gay rights activist Andrew Hodges. It stars Benedict Cumberbatch as the British cryptanalyst Alan Turing, who, working with a team of experts at the country estate Bletchley Park, devises a machine that, after much trial and error (and official interference) cracks the Germans’ notoriously difficult Enigma communications code. This breakthrough turns the tide of World War II and hastens Germany’s defeat. Turing is later prosecuted by a British court for his homosexuality and commits suicide as a result of the hormone treatment he is forced to endure.

The film was a huge commercial success (grossing $219 million against a $14 million production budget), received many award nominations, and won an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay. However, while The Imitation Game was critically acclaimed, it was also slated for its many historical inaccuracies. Largely neglected in all the commentary about the Weinstein Company’s historical drama is the Jewish ethno-political agenda that runs through the film.

One Jewish source notes that, despite Benedict Cumberbatch being “so gentile it’s almost shocking,” the film has “significant Jewish angles” while being about “a non-Jewish mathematical genius from Cambridge University, Alan Turing, and his efforts to crack Nazi codes in the bucolic British countryside.” It admits that, given the Jewish domination of Hollywood, “perhaps it’s not shocking that the film’s producers are Jews (the clues are there in ‘film’ and ‘producers’)”—these producers being Ido Ostrowsky, Nora Grossman, and Teddy Schwarzman (the son of billionaire Jewish financier Stephen Schwarzman) who “were drawn to Turing’s story as a tale of a brilliant outsider forced to work with others to win the war against German evil.” Ah, the venerable heroic Jew as outsider theme.

Naomi Pfefferman, writing for The Jewish Journal claims that Turing’s efforts shortened the war and “saved up to 14 million lives, including those of millions of potential Holocaust victims,” and observes that:

For the Israeli-born Ostrowsky — who moved to Los Angeles with his family when he was a baby — there was another point of connection to Turing’s work: Ostrowsky’s Russian-Jewish grandparents lost relatives in Nazi concentration camps, and Ostrowsky is keenly aware that he, too, as a gay Jewish man, would have worn both the pink triangle and the yellow Jewish star during the Third Reich. Of the millions of lives Turing saved, he said, “I thought about how many of those people might have been my family members; it really hit close to home that Turing was a hero for all people, but also my people. And then he was treated in such a horrific way; it just felt like a shocking injustice. Even though he was officially pardoned after we shot our movie, it felt like he had never properly been celebrated or brought back to his rightful place in history.”

Turing’s story also resonated with fellow producer, Nora Grossman, whose “great-grandfather, Benjamin Grossman, migrated to Ventnor [New Jersey] from Poland just before World War II” while most of his family who remained “perished in ghettos.” Grossman’s cousin, Gail Rosenthal, is the director of a Holocaust Resource Center at Stockton College in New Jersey. Having watched the film, a representative from the center opined that “The movie was very powerful on multiple levels,” and claimed that, “On one level, the film deals with stopping the biggest bully of all time, Hitler. But it also shows how Turing himself was bullied as a kid in school and later in life. It’s ironic that the man who helped defeat the biggest bully of all time met his demise as a result of bullying.”

Former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown summed up the line of thinking that motivated the many Jews involved in the production of The Imitation Game when, writing in praise of Turing in 2009, he contended that:

Alan deserves recognition for his contribution to humankind. For those of us born after 1945, into a Europe which is united, democratic and at peace, it is hard to imagine that our continent was once the theatre of mankind’s darkest hour. It is difficult to believe that in living memory, people could become so consumed by hate — by anti-Semitism, by homophobia, by xenophobia and other murderous prejudices — that the gas chambers and crematoria became a piece of the European landscape as surely as the galleries and universities and concert halls which had marked out the European civilization for hundreds of years. It is thanks to men and women who were totally committed to fighting fascism, people like Alan Turing, that the horrors of the Holocaust and of total war are part of Europe’s history and not Europe’s present. So on behalf of the British government, and all those who live freely thanks to Alan’s work, I am very proud to say: we’re sorry. You deserved so much better.

In 2010 Ostrowsky and Grossman pooled their money and bought the rights to Andrew Hodges’ biography. At the time, Grossman was working at the Jewish-owned and controlled DreamWorks studio in the TV department and Ostrowsky was working at the Jewish-controlled NBC. The next step in bringing Turing’s story to cinematic life was to find someone to adapt the book into a screenplay. Inevitably, their choice of screenwriter involved Jewish ethnic networking. Grossman “chanced” to invite the young Jewish writer Graham Moore to her home for a party in 2010. She was discussing her “Alan Turing project” with a friend and recalls how “Graham, whom I had known from my television days, was actually involved in another conversation, but he overheard me, interrupted me and said, ‘I love Alan Turing!’” As soon as he discovered Grossman and Ostrowsky had optioned the rights to Andrew Hodges’ book, he lobbied for the chance to tell the story of “his underappreciated, lesser-known childhood hero.”

Moore, who at that time was writing a sitcom for ABC Family (a subsidiary of the Jewish-owned and managed Disney), recounts how:

I was at a party at Nora’s house, and at the time I didn’t know her particularly well, but I asked her what she had been up to and she said, “Well, I just used a chunk of my own money to option a book,” and I said, “Oh, that’s really cool, cheers! Have a drink, that’s great, doing your own thing! What’s the book about?” and she said, “This mathematician, you’ve never heard of him.” And I said, “Well, I do know a little bit about mathematics,” and when she said “Alan Turing,” I instantly freak out and launch into this totally insufferable 15-minute monologue about how I’ve dreamed about writing about Alan Turing since I was a little kid, I went to computer camp, where all we ever talked about was Alan Turing. This is what the movie is, this is how it starts, and I could see her start to inch back step by step, trying to get away from me. But somehow I convinced her to let me do it.

As with Grossman and Ostrowsky, Moore’s fascination with Turing is a product of his Jewish identity and sympathies. The son of two lawyers, Moore grew up on the north side of Chicago in a family with a deep commitment to leftwing politics. The Tablet notes that Moore’s mother is “not just any Yiddishe Mameh” but Susan Sher, who, during the first term of the Obama administration served as special assistant to President Obama and then as chief-of-staff to Michelle Obama (whom she first met in 1991). These jobs were in addition to her role as the official White House liaison to the Jewish community, “a realm that has become increasingly important to her son.”

Moore has always felt strongly connected to the Jewish community. “My Judaism has felt more and more important to me, and more and more of a social identifier,” he told The Jewish Journal. “My grandparents passed away a few years ago, and I was very close to them, and for their generation, their Jewish identity was extremely important. And after they passed away, this notion that me [sic] and my mother would become the keepers of this tradition became very apparent and very important.” Moore’s mother is currently involved in “advocacy” to build the Obama Presidential Library on the South Side of Chicago as part of her role as senior advisor to University of Chicago President Robert Zimmer (who, inevitably, is also Jewish).

Despite being the privileged representative of the wealthiest, most well-connected and powerful ethnic group in the United States — and someone who attended Colombia University (where he became editor of the student newspaper) — Moore sees himself as an “outsider” who is alienated from the American mainstream. “I think I always felt like an outsider, like a weirdo,” he claimed — a condition which, according to Danielle Berrin, writing for the ‘Hollywood Jew’ section of The Jewish Journal, has “afflicted almost every artist that ever lived, not to mention, almost every Jew.”

In addition to his putative “outsider” status, Moore is stereotypically Jewish in other ways, reportedly being “hyper-articulate, to the point where he needs only a simple prompting to riff energetically on a number of subjects, and his ability to speak on a range of topics suggests the diversity of his interests — technology, journalism, rock music and politics.” Moore is also, inevitably, a “genius.” Berrin claims, for instance, that taken together, Moore’s “back-to-back successes,” suggest that he “is either experiencing an unheard of bout of beginner’s luck, or he is, perhaps, like the subjects on which he writes, something of an anomalous genius himself.”

The screenwriter of The Imitation Game grew up with a small group of friends who were “a very motley bunch of outsiders.” He claims that “Some of us were gay, some were straight, but most of us wore nail polish. (I certainly did). Occasionally, lipstick and eyeliner.” His best friend was the “NYU film grad Ben Epstein,” who suggested they become writing partners. Upon graduation Epstein quickly secured work in Hollywood as a writer, producer and director for numerous shows including the 2014 series Happyland for Sumner Redstone’s pestilential MTV. Moore, like Epstein was irresistibly drawn to Hollywood, where one of his earliest jobs was as a staff writer for the short-lived series 10 Things I Hate About You. Moore’s real breakthrough, however, was his novel The Sherlockian which was on the New York Times bestseller list for three weeks.

Alan Turing was a figure that meant a lot to Moore from a young age, and he claims to have become “obsessed with this idea that his cryptographic work and his computer work is him dealing with the issues of being a closeted gay man. … One of the things I found so fascinating about him is that he was someone who didn’t fit into the society around him for many different reasons.” Moore could also identity with Turing being “the smartest person in every room that he entered,” and, while apparently not being homosexual himself, sympathized with the plight of a man, who, “when the government found out he was gay, he was arrested, persecuted by the country he’d just saved from Nazi rule, until he finally committed suicide.” Moore told the L.A. Times that:

Once I heard the story, I wanted to learn more. I needed to learn everything I could about him. Alan Turing was an outsider’s outsider — perhaps the most brilliant scientist of his generation, a social outcast who produced theories decades ahead of their time. A gay man who was able to keep secrets for the government so well precisely because he’d been forced to spend his entire life keeping his sexuality secret from a world in which a kiss between two men was literally punishable by two years in prison. For a weird kid like myself, who never felt like he belonged or fit in, Alan Turing wasn’t just an inspiration — he was a patron saint. (As a Jew, my mother would be aghast to hear me describe anyone as a saint, but you get the idea).

Moore’s screenplay has been criticized for its numerous historical inaccuracies and clichéd characterizations. Writing in the New York Review of Books, Christian Caryl accused the film in general and Moore specifically of “monstrous hogwash,” “caricature” and a “bizarre departure from the historical record.” L.V. Anderson, reviewing The Imitation Game for Slate, similarly observed that Moore “takes major liberties with its source material, injecting conflict where none existed, inventing entirely fictional characters, rearranging the chronology of events, and misrepresenting the very nature of Turing’s work at Bletchley Park.”

Moore’s characterization of Turing is deeply flawed. His claim that Turing was someone who was “forced to spend his entire life keeping his sexuality secret from a world” is simply wrong. Hodges’ biography is filled with instances where he boldly propositioned other men — mostly without success. Turing also told his friends and colleagues about his homosexuality. Caryl points out that Moore’s false characterization “is indicative of the bad faith underlying the whole enterprise, which is desperate to put Turing in the role of a gay liberation totem.” He notes that the film’s factual errors “are not random; there is a method to the muddle. The filmmakers see their hero above all as a martyr of a homophobic Establishment, and they are determined to lay emphasis on his victimhood.”

Moore strongly implies (again contrary to Hodges’ biography) that Turing is somewhere on the autism spectrum: he never gets jokes, takes common expressions literally, and is totally indifferent to the annoyance and offence his behavior causes others. While Hodges describes Turing as a man who is eccentric and impatient with irrationality, he also observes that he had a keen sense of humor and was charming with friends and trusted colleagues. One of these colleagues at Bletchley Park later recalled him as “a very easily approachable man” and said “we were very very fond of him.” None of this is reflected in Moore’s screenplay (or the film) which instead reduces Turing to a caricature of the tortured genius. Caryl observes that:

Turing (played by Benedict Cumberbatch) conforms to the familiar stereotype of the otherworldly nerd: he’s the kind of guy who doesn’t even understand an invitation to lunch. This places him at odds not only with the other codebreakers in his unit, but also, equally predictably, positions him as a natural rebel. … The film spares no opportunity to drive home his robotic oddness. He uses the word “logical” a lot and can’t grasp even the most modest of jokes. … On various occasions throughout the film, [the chief codebreaker at Bletchley Park] Denniston tries to fire Turing or have him arrested for espionage, which is resisted by those who have belatedly recognized his redemptive brilliance. “If you fire Alan, you’ll have to fire me, too,” says one of his (formerly hostile) coworkers.

All of this is pure invention by Moore. In reality, Turing was a willing participant in the collective enterprise at Bletchley Park that featured a host of other outstanding intellects (including Denniston) with whom he happily coexisted. Ignoring this, Moore is determined to suggest maximum dramatic tension between their tragic outsider and a blinkered establishment. “You will never understand the importance of what I am creating here,” he has Turing wail when Denniston’s minions try to destroy his machine (which again never happened). L.V. Anderson notes that:

the central conceit of The Imitation Game — that Turing singlehandedly invented and physically built the machine that broke the Germans’ Enigma code — is simply untrue. A predecessor of the “Bombe”—the name given to the large, ticking machine that used rotors to test different letter combinations—was invented by Polish cryptanalysts before Turing even began working as a cryptologist for the British government. Turing’s great innovation was to design a new machine that broke the Enigma code faster by looking for likely letter combinations and ruling out combinations that were unlikely to yield results. Turing didn’t develop the new, improved machine by dint of his own singular genius—the mathematician Gordon Welchman, who is not even mentioned in the film, collaborated with Turing on the design.

Turing’s “bombes” — electromechanical calculating devices designed to reconstruct the settings of the Enigma — were already being used to decipher German army and air force codes from early in the war.

Moore’s account of Turing’s arrest and death also distorts the facts. In his screenplay, Moore has Turing investigated by police on suspicion of spying for the Soviet Union and when they, pursuing this line of enquiry, discover his homosexual lifestyle, it leads to his arrest. Contrary to the film’s depiction, it was Turing himself who alerted the police to his homosexuality by reporting a petty theft from his home to the police and then changing the details of his story to cover up a relationship with the suspected culprit, the 19-year-old Arnold Murray. It was Turing’s own actions which brought his homosexuality to the attention to the police and which led to legal proceeding against him. Turing was convicted on indecency charges in 1952, and chose a therapy involving female hormones — aimed at suppressing his unnatural desires — as an alternative to jail time.

Turing’s other biographer, B. Jack Copeland, disputes the assertion in the film that this treatment sent Turing into a downward spiral of depression. By the accounts of those who knew him, he endured it with fortitude, and spent the next year enthusiastically pursuing projects. Copeland cites a number of close friends (and Turing’s mother) who saw no evidence that he was depressed in the days before his death, and notes that the coroner who concluded that Turing had died by biting a cyanide-laced apple never actually examined the fruit. Copeland offers compelling evidence that his death was accidental, the result of the accidental inhalation of cyanide fumes from a device used for electroplating spoons with gold. In statements to the coroner, friends had attested to Turing’s good humor in the days before his death. Turing also left no suicide letter.

Even if one accepts that Turing was driven by the “homophobic establishment” to his self-inflicted death, The Imitation Game’s depiction of his fate is ridiculous. In one of the film’s most egregious scenes, his wartime friend Joan pays him a visit in 1952 or so, while he is still taking the hormones. She finds him dementedly shuffling around the house in his bathrobe. He tells her that he’s terrified that the authorities will take away “Christopher”—his latest computer, which he’s named after the dead friend of his childhood (just as he did with his machine at Bletchley Park). Caryl notes that this scene is “monstrous hogwash, a conceit entirely cooked up by Moore,” while Anderson observes that “Turing did not call any of the early computers he worked on ‘Christopher’ — that is a dramatic flourish invented by screenwriter Graham Moore.”

Clearly it is only Turing’s homosexuality, and his devotion of his talents to the cause of defeating the Germans that makes his story palatable to the many Jews involved in the production of The Imitation Game. Lest an audience be led to assume that a White man (albeit a homosexual White man) should take all the credit for breaking the Enigma Code, one Jewish source is eager to assure its readership that Jewish historian Martin Sugarman “has painstakingly pointed out, [that] among the 7,000-8,000 staff working at Bletchley during the war were perhaps 200-300 Jews.”

Moore goes even further than Sugarman and embroiders an episode from Hodges’ biography to create the impression that Turing was Jewish (or at least was a victim of the “anti-Semitic” mentality of 1920s Britain). The scene, where a young Turing is trapped under the floorboards of a partially-built classroom by other schoolboys, is written by Moore as follows:

CUT TO:

INT. COFFIN — A FEW MINUTES LATER

… Alan is now inside a coffin.

He’s KICKING AT THE WOODEN BOARDS ABOVE and SCREAMING TO BE RELEASED.

It’s not helping.

From above, we hear the familiar LAUGHTER OF THE SCHOOLBOYS.

REVEAL: The “coffin” is make-shift; the Boys have constructed it out of the broken floorboards of a half-finished class room. Alan is buried underground, and they’re nailing him in.

ALAN TURING (Voice Over) Do you know why people like violence? Because it feels good.

The THUMP THUMP of nails entering the boards.

ALAN TURING (Voice Over) Humans find violence deeply satisfying. But remove the satisfaction, and the act becomes… Hollow.

FROM INSIDE THE COFFIN: Alan goes silent. The Boys pound away, but the silence unnerves them.

BOY #1 Alan? Alan?

BOY #2 C’mon don’t be such a kike about it…

BOY #3 Leave him to bloody rot.

The Boys LEAVE.

There’s still only SILENCE from inside Alan’s coffin. Alan breathes slowly. Quietly. Controls his shivering to barely a tremor. He waits.

ALAN TURING (Voice Over) I didn’t learn this on my own though. I had help.

Suddenly, the boards above him CREAK. Then BEND. Then SNAP.

Then an ARM REACHES DOWN and PULLS Alan out of the coffin.

REVEAL: CHRISTOPHER MORCOM, 16, tall, pretty, and charming in ways that Alan will never, ever be.

CHRISTOPHER Christ, I thought they were going to kill you.

This scene can be viewed here (from 0:29). Turing is called a “kike” by another boy — despite the fact that he was not Jewish, was never assumed to be Jewish, and that the epithet “kike” (which is probably an American coinage) was not in common usage in England in the 1920s.

Arguing that his screenplay is a work of art rather than a historically accurate record of events, Moore has shrugged off all criticism, and claiming artistic license, argued that:

To criticize a film for ‘historical accuracy’ is to fundamentally misunderstand what art is and how art works. … No one looks at one of Monet’s paintings of water lilies and says to themselves ‘Oh my God, that’s not what a water lily looks like.’ The intention of a piece of art like that is to create in the viewer the sensation of what looking at water lilies feels like; and I think the same is true of a piece of narrative cinema. The point is to create the sensation of Alan Turing, to put the audience inside of Alan Turing’s head, and for two hours let them see the world the way he did.

The many historical inaccuracies of his screenplay certainly did not prevent the 33-year-old Moore from winning this year’s Academy Award in the Best Adapted Screenplay category. In his acceptance speech he made a plea for homosexual rights which led many to assume he was gay. He later clarified that he was not, but “that it was the broad strokes of Turing’s story [i.e. the putative victimhood] that resonated with him more than just his sexual orientation.” Hollywood is so dominated by an intensively networked coterie of Jews that Moore even competed for an Oscar with his Jewish ex-girlfriend Helen Estabrook, who served as a producer for the Oscar-nominated Whiplash which was up against The Imitation Game for Best Picture.