Diversity Macht Frei

January 28, 2017

Happy International Holocaust Memorial Day everyone! To celebrate this special occasion, Laurence Rees was invited on to Sky News today, where he shared his thoughts about what led to the Holocaust and what leads to antisemitism more generally. Rees is the author of the recently published “The Holocaust: A New History” as well as previous books on related themes. As former director of history programming for the BBC, he oversaw innumerable documentaries about the conservative revolution in Germany (“The Nazis: A Warning from History”). He even set up a website to help correct the thoughts of anyone whose interpretations of WW2 were beginning to stray in improper directions (link).

When asked why antisemitism still exists, he replies:

A whole number of the arguments – false arguments – the Nazis used are still alive with a minority of people. For example in the east the crude equation of Judaism with Communism. So “We’re against Communism, we hated what the Communists did, they were all run by Jews you know”. I mean it’s nonsense at one level but it becomes an easy kind of way in.

The refusal of Jews to acknowledge that they bear some measure of guilt for Communism, and the atrocities – including tens of millions of deaths – it gave rise to, is the real Holocaust denial. No hate speech laws criminalise this Holocaust denial. No 87-year-old women are sent to prison for daring to utter it. On the contrary, all the ranks of official historians rally behind this falsehood, even though it makes the history of the 20th century otherwise incomprehensible.

To establish the facts let us quote from some academic literature on the subject. Here are some extracts from the book “Dark Times, Dire Decisions: Jews and Communism”, edited by Jonathan Frankel, which features essays on the subject of Jews and Communism by various historians, all or almost all of whom appear to be Jewish. Yes, here and there, in obscure places, when they think the goy aren’t listening, Jews have acknowledged the truth. Now we need them to acknowledge it publicly.

The first is titled “Jews and Communism: The Utopian Temptation” by Dan Diner, THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY, UNIVERSITY OF LEIPZIG

BEGIN CITATION

Jews were at times attracted in disproportionate numbers to the Communist movement precisely because it promised an escape from the realities of life within a minority marked off variously by ethnic, religious, and socioeconomic boundaries into a new world where all such boundaries would be eliminated. However, the presence of a relatively large number of Jews (by origin, although for the most part not by allegiance) in the Communist ranks, and especially in the upper party echelons, had as one of its results the exacerbation of hostility among broad strata of the population toward both Communism and the Jewish people.

Rather than breaking down hostility between nationalities, the conspicuous presence of Jews in the party served to augment traditional anti-Jewish resentment. This was true even though Communists of Jewish origin were never more than an extremely small percentage of the total Jewish population in any given country.

… For their part, faced by mounting antisemitic enmity from within large sections of society, Jews in increasing numbers fell back on the Communist movement (when it was out of power and in opposition to right-wing governments) and on the Communist regimes (once they were established). This reaction served to aggravate antisemitism still further.

Thus, the potentially catastrophic effects of the identification of Jews with Communism can best be visualized not so much as a circle—a vicious circle—but rather as a spiral driven upward and outward by fear, hatred, and violence. That this would be the case should have come as no surprise. The dangers inherent in the association (real, but still more imagined) of Jews with the Left had become apparent long before the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917 and the creation of the Communist regime.

For decades, conservative and ultra-right forces in tsarist Russia had accused the Jews (socialists, anarchists, liberals) of spearheading revolution and hence of bringing the pogroms of 1881–1884 and 1903–1906 upon themselves. At the same time, the anger and loathing produced by the discriminatory policies of the regime and, even more, by the hundreds of pogroms, only served to increase the number and commitment of young Jews to the revolutionary cause.

This same cycle of actions and reactions had in fact emerged still earlier, albeit on a far lesser scale, in Central Europe during the Vormärz period and the revolutions of 1848. It was then that the “Jewish question” had first emerged as a key subject of political controversy in the German-speaking lands as, indeed, also in France. On the Right, conservatives perceived the demands for Jewish emancipation as an attack on the Christian state and therefore as a major threat to the very foundations of the established order, whereas on the Left, the grant of civil equality to the Jews was seen as an inevitable step toward a constitutional, a democratic, or even a socialist future.

… What had heretofore been mere issues of public debate took on far more acute significance during the revolutionary years of 1848–1849. It is enough to mention the widespread outbursts of anti-Jewish violence, motivated variously by ethnic, political, and economic factors (most specifically the identification of the Jews as the moneylenders and the bankers); the role played by revolutionaries of Jewish origin in the insurrectionary events (Fischhof and Goldmark in Vienna, Marx and Hess in the Rhineland, Jacoby in Königsberg, Crémieux and Goudchaux in Paris, Manin in Venice); and the mounting tendency within the ancien régime to see the revolutions as somehow rooted in Jewish interests, led by Jews and therefore totally illegitimate.

Nonetheless, it was during the years 1918–1920 that the full implications of the association of Jews with the revolution, and specifically with the Communist revolution, first became apparent. With a striking number of Jewish-born individuals in the Bolshevik leadership—Trotsky, Kamenev, Zinoviev, Sverdlov, and Uritsky to name just the most conspicuous—it was inevitable that the new regime should find itself branded as being dominated by Jews. From that premise, it was not far to the assertion that the Bolshevik revolution was part of a conspiracy designed to win domination for the Jewish people in Russia and eventually throughout the world.

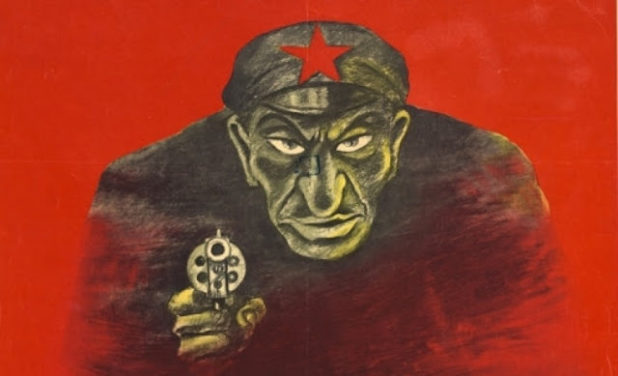

This theory was lent apparent plausibility in the spring of 1919, when insurrections culminated in the installment of Communist-led regimes in Hungary and Bavaria and in the sudden prominence of even more Jews at the top—some party members, others nonaffiliated pro-Soviet socialists, and still others anarchists (among them, Béla Kun in Budapest and Kurt Eisner, Ernst Toller, and Gustav Landauer in Munich). From the traditionalist perspective, the images of Leon Trotsky standing at the head of the Red Army, and of the Jewish Chekist in leather jacket with a Mauser pistol carrying out mass liquidations, conjured up an existential threat of demonic proportions.

Seeking an explanation for this otherwise inexplicable reversal of the hallowed order of things, opponents of the revolution found it in the idea that world Jewry was intent on gaining control of the entire globe. It was now that the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which exposed, as it were, the inner workings of this vast conspiracy, first became an extraordinary best-seller across Europe.

Thus, it was hardly a cause for surprise that Hitler and the Nazi party should have defined their primary enemy as the interlocking force of world Jewry and world Communism (organized since 1919 in the Communist International, or Comintern). Theories of this kind had been incubating over the previous century and now could be seen as confirmed by reality.

This extract is from another essay in the same book, titled “Jews and the Communist Movement in Interwar Poland” by Jaff Schatz of INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH CULTURE, LUND.

BEGIN CITATION

As previously suggested, throughout the interwar period, Jews did constitute an important segment of the Communist movement. According to both Polish sources and Western estimates, the proportion of Jews in the KPP was never lower than 22 percent countrywide, reaching a peak of 35 percent (in 1930). According to some available data, the level of Jewish members of the Communist movement then dropped to no more than 24 percent for the remainder of the decade. Other data, however, indicate that Jewish membership actually went up in the large cities; in Warsaw, for example, Jewish membership rose from 44 percent in 1930 to more than 65 percent in 1937.

In the semi-autonomous KPZU and KPZB, the percentage of Jewish members was similar to that in the KKP. The number and proportion of Jewish members in the youth movements was even higher, ranging from 31 percent to a high of 51 percent.

Working on the assumption that Polish Jewish Communists constituted between a quarter and a third of the Communist movement during the 1930s, the total of Polish Jewish Communists (including youth group members but excluding political prisoners) ranged between 5,000 and 8,400. If prisoners are included, the numbers range between 6,200 and 10,000.

In addition, Jews comprised the overwhelming majority of one of the legal front organizations, the Polish-based International Organization for Help to the Revolutionaries (Międzynarodowa Organizacja Pomocy Rewolucjonistom “MOPR”), which collected money for and channeled assistance to imprisoned Communists. In 1932, out of 6,000 members of the MOPR, about 90 percent were Jews.

Perhaps even more significant was the Jewish representation among the Communist movement leadership. Although party authorities consciously strove to promote classically proletarian and ethnically Polish members to become leaders and party functionaries, Jews accounted for 54 percent of the field leadership of the KPP in 1935 and 75 percent of the party’s technika—those responsible for producing and distributing propaganda materials. Communists of Jewish origin also occupied a majority of the seats on the Central Committees of both the Komunistyczna Partia Rabotnicza Polski (KPRP) and the KPP.

END CITATION

Similar data could be provided for many other countries. For the sake of not making this post unduly long, I’ll leave it there. Perhaps I’ll turn this post into a series. It is utterly shameful that these facts of history continue to be denied and that, in many countries, any non-Jew who dares to draw attention to them risks being prosecuted for “hate speech”.