Federale

VDARE

September 25, 2015

Much has been written on the issue of birthright citizenship. Many claim that the 14th Amendment settled the issue for all time by proclaiming all persons born in the United States are citizens, including children born to illegal aliens.

Much has been written on the issue of birthright citizenship. Many claim that the 14th Amendment settled the issue for all time by proclaiming all persons born in the United States are citizens, including children born to illegal aliens.

Some claim that given the wording in the 14th Amendment, only children of legally present non-diplomat aliens can pass citizenship on to a child born in the United States. The real answer is that no, not even children of legal resident aliens can receive citizenship at birth automatically.

The critics of birthright citizenship for illegal aliens have arguments in their favor, both the law and the facts. The first being the wording of the 14th Amendment which presupposes numerous exceptions for birthright citizenship expressly limiting citizenship: All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. The operative clause is “…and subject to the jurisdiction thereof…”

NRO, August 24, 2015, by John Eastman

We Can Apply the 14th Amendment While Also Reforming Birthright Citizenship

This claim plays off a widespread ignorance about the meaning of the word “jurisdiction.” It fails to recognize that the same word covers two distinctly different ideas: 1) complete, political jurisdiction; and 2) partial, territorial jurisdiction. Think of it this way. When a British tourist visits the United States, he subjects himself to our laws as long as he remains within our borders. He must drive on the right side of the road, for example. He is subject to our partial, territorial jurisdiction, but he does not thereby subject himself to our complete, political jurisdiction. He does not get to vote, or serve on a jury; he cannot be drafted into our armed forces; and he cannot be prosecuted for treason if he takes up arms against us, because he owes us no allegiance. He is merely a “temporary sojourner,” to use the language employed by those who wrote the 14th Amendment, and not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States in the full and complete sense intended by that language in the 14th Amendment.

Clearly the major exception was Indians, who were not subject to the complete political jurisdiction of the United States and were not considered citizens despite physical presence in the United States.

Texas Review of Law And Politics, November 2010, by Lino Graglia

Birthright Citizenship For Children Of Illegal Aliens: AnIrrational Public Policy

In the 39th Congress, which enacted the 1866 Civil Rights Act and proposed the Fourteenth Amendment, the question arose of how to avoid granting birthright citizenship to members of Indian tribes living on reservations. The issue was whether an explicit exclusion of Indians should be written into the Citizenship Clause as it was in the above-quoted first sentence of the 1866 Act. It was decided that this was not necessary, because, although Indians were at least partly subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, they owed allegiance to their tribes, not to the United States.

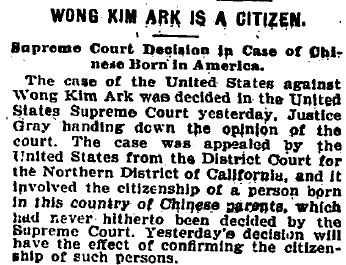

Similarly, the celebrated case of Wong Kim Ark, born to Chinese immigrant parents in California, but whose parents were legally living in the United States when he was born, but whom subsequently returned to China, as did Wong.

Wong was detained when returning from China and he sought a writ of habeas corpus for release and recognition of his claim to American citizenship. The subsequent decision stated that given birth in the United States to legal immigrants, Wong was a citizen.

However, given the arguments of Eastman and Graglia, specifically, the principle that jurisdiction includes political loyalty, Wong loses on the facts, as do all aliens, legal or illegal. Both groups must be naturalized before they can become citizens of the United States.

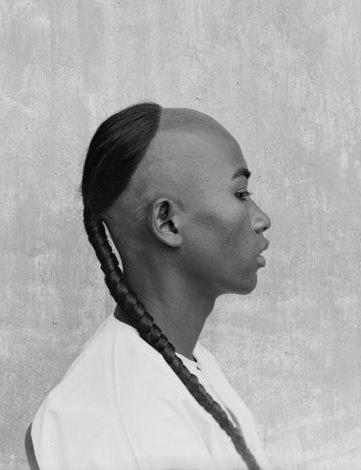

First, a photograph of Wong, note his dress and hair style. Those are of important political significance and reflect on his adherence to a foreign power. This photograph is from an identification document necessary for Wong to have to return to the United States from yet another trip to China, given that he needed to prove his citizenship to return due to the Chinese Exclusion Act, that prohibited, for the most part, the entry of Chinese citizens into the United States for permanent settlement.

First, Wong is wearing what was called then a Chinese pigtail, but more accurately known as a queue, specifically a Manchu queue. The Manchus, a barbarian tribe of horse mounted warriors, much similar to the Mongols, who also previously ruled China as the Yuan Dynasty, were the rulers of the Chinese Empire, the Middle Kingdom as the Chinese called their Empire, from 1644 to 1911.

The Manchus adopted much of Chinese political, religious, and social custom when they established their dynasty, the Ch’ing Dynasty. However, they maintained, or tried to maintain, a separate system of racial hygiene, that maintained the Manchu language, dress, and martial vigor within the ostensibly Sinified ruling class. That was followed more in the breach, but at the beginning of the Ch’ing Dynasty and following until the establishment of the Chinese Republic, Ch’ing officials vigorously maintained the requirement that all Han males, e.g. racially Chinese, subjects wear their hair in the Manchu queue, a shaved forehead with the rest of the hair worn uncut in a braid.

And the Ch’ing enforced this mandate with ruthless vigor.

China Heritage Quarterly, September 2011, by Michael R. Godley

The head-shaving edict was extended to the rest of the population; Dorgon ordered the Board of War to crush opposition but subsequently rescinded the order on the grounds that ‘it contradicted the will of the people.’ Nevertheless, the capital and its environs were properly groomed by the time the young emperor arrived in November 1644. After the fall of Nanjing the following July, another decree was issued—this time more diplomatically through the Board of Rites. Although this edict has entered popular myth as amounting to the sentiment ‘off with your hair or off with your head,’ and armed barbers allegedly carried the severed heads of recalcitrants on bamboo poles to show the double-edged nature of their profession, Dorgon’s rescript was comparatively restrained. After noting that his earlier orders had not been enforced in the hope that males would conform of their own volition, he appealed to Confucian precepts: ‘Now that the country has become as one family, the ruler is like a father and the people are like sons … How can they be different or distant?’ Nonetheless, the throne was more than willing to employ coercion if this milder approach failed, for the edict also warned that the laws of the new dynasty had to be obeyed. More to the point, hair was a sure way to distinguish ‘our subjects’ from ‘those bandits who oppose our mandate.’

Mandate refers to the Mandate of Heaven, the blessing of the gods that provides the underpinning to political legitimacy in the Confucian system.

Here the barbarian Emperor is claiming he holds political legitimacy in China and all Han owe him their loyalty and obedience. To not wear the queue was an act of rebellion against the political will of the Chinese state, but for Wong, despite his birth in America, he maintained his queue, as well as traveling frequently back to China.

Furthermore, Wong wears the costume of the Manchu as well. What is commonly called a Mandarin collar, the high collared jacket that so many in the West associate with China, is in fact an item of Manchu origin, also mandated by the Manchus as a symbol of political loyalty to Ch’ing Dynasty.

Taken together, along with Wong’s frequent and long sojourns in China, show that he, like the American Indians, were not subject to what Eastman calls the full political jurisdiction of the United States, but merely under the physical jurisdiction of the United States. Wong told the world his primary political loyalty was to the Emperor of China, not to the United States, same with his parents who moved back to China, in accordance with their political and cultural loyalty to China, even an alien occupied China, just as Indians held their primary loyalty to their respective tribes.

So, just on the principle of complete political jurisdiction, Wong was not a citizen and required naturalization, as determined by Congresses Article 1, Section 8 authority. Similarly, current legal and illegal aliens from most countries maintain citizenship in the country of their parents; Mexico, for example, extends citizenship to all person born abroad to one or more Mexican parents, so it is both practical and appropriate for children of legal and illegal aliens to not be accorded U.S. citizenship, but remain, not stateless, but citizens of the country of their parents, as all countries practice. The solution is a naturalization process for the children of legal immigrants testing loyalty, English language skills, and civics, just as other legal permanent resident aliens are required to complete if they want to become American citizens.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History