The New Observer

January 20, 2016

One year of teaching in a nonwhite New York school turned Ed Boland, a raving liberal in that city, into someone who “loathed and despised” the “students” he had set out to help—and convinced him that they are irredeemably at the bottom of the social heap.

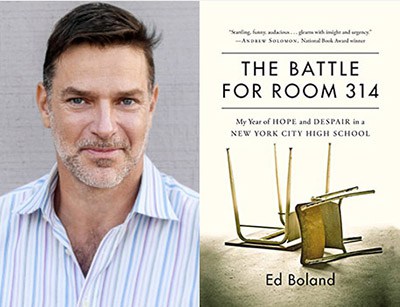

The astonishing story of Boland’s exposure to the chaos that has become the US public school system, following the massive growth of America’s Third World population, is the subject of a book he has just published, titled The Battle for Room 314: My Year of Hope and Despair in a New York City High School.

More incredibly, the usually far-left and anti-white New York Post (NY Post) has published a very objective—and even sympathetic—review of Boland’s book, which provides a dramatic insight into the Third World nightmare that has become New York City public schools.

The NY Post article, titled “My year of terror and abuse teaching at a NYC high school,” reveals that although Boland changed the name of his school (and his “students”) in the book, “the school Boland calls Union Street is, according to clues and public records, the Henry Street School of International Studies on the Lower East Side.”

According to the official NYC government “schools report” website, the Henry Street School for International Studies (Lower/Middle and High schools) has a white student population of “4 percent.”

Boland’s book reveals that during his one year tenure there—in 2008—there was exactly one white pupil at the school.

As the NY Post review says, Boland was a “well-off New Yorker who had spent 20 years as an executive at a nonprofit” who had a “midlife epiphany: He should leave his white-glove world, the galas at the Waldorf and drinks at the Yale Club, and go work with the city’s neediest children.”

His book, the NY Post says, is a “memoir of his brief, harrowing tenure as a public school teacher, and it’s riveting. There’s nothing dry or academic here. It’s tragedy and farce, an economic and societal indictment of a system that seems broken beyond repair.”

It starts with a “typical morning in freshman history class:”

A teenage girl named Chantay sits on top of her desk, thong peeking out of her pants, leading a ringside gossip session. Work sheets have been distributed and ignored.

“Chantay, sit in your seat and get to work — now!” Boland says.

A calculator goes flying across the room, smashing into the blackboard. Two boys begin physically fighting over a computer. Two girls share an iPod, singing along. Another girl is immersed in a book called Thug Life 2.

Chantay is the one who aggravates Boland the most. If he can get control of her, he thinks, he can get control of the class.

“Chantay,” he says, louder, “sit down immediately, or there will be serious consequences.”

The classroom freezes. Then, as Boland writes, “she laughed and cocked her head up at the ceiling. Then she slid her hand down the outside of her jeans to her upper thigh, formed a long cylinder between her thumb and forefinger, and shook it .?.?. She looked me right in the eye and screamed, ‘SUCK MY F–KIN’ D–K, MISTER.’?”

It was Boland’s first week.

Boland’s decision to take part in this teaching year, it is revealed, was endowed in part by the [Bill] Gates Foundation, and the principal hired only teachers who had once lived abroad, NY Post revealed.

Boland’s decision to take part in this teaching year, it is revealed, was endowed in part by the [Bill] Gates Foundation, and the principal hired only teachers who had once lived abroad, NY Post revealed.

Boland, it seems, had taught English in China. “This was his favored school — advertised as the last, best hope for kids who had fallen far behind — and he was thrilled to be hired.”

“I was ready to change lives as a teacher,” he writes.

“How wrong he was,” says the NY Post, as it goes on to describe further extracts from his book:

He had rounded up his students into a semicircle and checked for forbidden items: phones, electronics, sunglasses, clothing in gang colors. Then someone kicked in the door.

And there, Boland writes, “stood one Kameron Shields in pure renegade glory, a one-man violation of every possible rule. Above the neck alone, he was flaunting four violations: He wore sunglasses and a baseball cap over a red bandanna over iPod headphones. A silver flip phone was clipped to his baggy jeans. Everything he wore was cherry red — the hallmark color of the Bloods.

“He turned his grinning face to the ceiling and howled, ‘WASS .?.?. UP .?.?. N—AS?’?”

Boland was outmatched. He was petrified. He ran out the clock and asked his fellow teachers who this kid was.

“Oh, yeah, he’s brutal,” one colleague said. Turned out Kameron had thrown a heavy electric sharpener at a teacher’s head the year before, but the principal — whom the teachers sarcastically called their “fearless leader” — refused to expel any student for any reason.

Two weeks in and Boland was crying in the bathroom. Kids were tossing $110 textbooks out the window. They overturned desks and stormed out of classrooms. There were seventh-grade girls with tattoos and T-shirts that read, “I’m Not Easy But We Can Negotiate.” Their self-care toggled in the extreme, from girls who gave themselves pedicures in class to kids who went days without showering.

Kameron was in a league of his own. “I was genuinely afraid of him from the minute I set eyes on him,” Boland writes. After threatening to blow up the school, Kameron was suspended for a few months, and not long after his return, a hammer and a double switchblade fell out of his pockets.

The principal gave up. Kameron was expelled.

“Oh, they getting real tough around here now,” one student said. “Three hundred strikes, you out.”

Here among the kids who couldn’t name continents or oceans, who scrawled, “Mr. Boland is a f—-t” on chalkboards, who listed porn among their hobbies, were a few who had a shot.

There was Nee-cole, who wore thick glasses and pigtails. She was quiet, smart, much more childlike than her peers, and Boland felt for her. He was also intrigued by a tough girl named Yvette, who showed flashes of insight and intelligence yet did all she could to hide it. “PLEASE DON’T TELL ANYONE I WROTE THIS,” she scrawled on one report.

He asked his fellow teachers about the enigma that was Yvette. “One day in class, I intercepted a note,” said a colleague, Tasneen. “It said, ‘Yvette b—s old guys for a dollar under the Manhattan Bridge.’ We punished the girl who wrote it for spreading lies.”

Soon after, the school heard from Child Protective Services. The prostitution rumor was true. Yvette was removed from her home. “She’s not doing it anymore,” Tasneen said, “but she’ll never outrun that story.”

Boland came to actively loathe most of the student body. He resented “their poverty, their ignorance, their arrogance. Everything I was hoping, at first, to change.”

His colleagues gave him pep talks, reminded him to contextualize this behavior: These kids had no parents, or abusive, neglectful ones. Most lived in extreme poverty. School was all they had, and it was their only hope.

A lifelong liberal, Boland began to feel uncomfortable with his thinking. “We can’t just explain away someone’s horrible behavior because they have had a tough upbringing,” he argued back. “It doesn’t do them — or us — any good.”

Then there was Jesús Alvarez, boyfriend of Chantay and, as Boland writes, “a perfect s-?-t.” Jesús would stroll by Boland’s classroom and shout, “Bolan’, who you ballin’? It ain’t no chick.”

Boland called in the father, even though he was warned it would do no good. The three sat down, and Boland was surprised.

“Jesús, this is a good school,” the father said. He warned Jesús that it was either school or the street, and Jesús wasn’t tough enough for the street. “You get yourself right, get an education, and show this man some respect.”

It was the one thing that had gone well so far. “I left that meeting brimming with confidence,” Boland writes. “Involving parents was key.”

One winter day, Bolan was mounting his bicycle, on his way home, when he saw a gang fight break out in a parking lot. He saw Jesús in the crowd, and an older man egging the kids on. “That’s it, Nelson, show that punk-ass bitch who’s boss. Whale his ass.”

It was Jesús’ father.

Next, he turned his attention to Valentina, a transfer student who joined his class in February. She wore tight jeans over what Boland calls “an epic derriere,” and as she walked to her seat, the kids oinked and mooed.

“Step down, all y’all n-?-?-as, or I’ll stab you in your neck,” Valentina said. “Don’t get me tight, bitches.”

Boland soon learned Valentina was what the Department of Education calls “a safety transfer” — meaning she was such a threat to her fellow students that she was pulled out of school.

Now here she was, Boland’s newest charge. He was quickly impressed with her observational skills — a bar he had set extremely low, now the victim of some inner-city form of Stockholm syndrome.

Asked to write about an ancient sculpture of two royals, Valentina wrote, “Well, isn’t it obvious that they are a couple? His hand is on her t—y .?.?. The way they sit is regal.”

It was the use of the word “regal” that blew Boland away. He pulled her aside after class.

“You can’t fool me,” he told her. “I can tell from just that one sheet of paper that you have a very fine mind.”

For that, he received an official complaint of sexual harassment, filed by one Valentina. She claimed Boland said, “You are mighty fine, you turn me on, and I can tell you like fooling around.”

The entire administration knew Boland was gay, yet they still had to follow procedure. He was never to be alone with Valentina again.

By the time he invited a highly decorated Iraq War veteran to speak to class and Valentina greeted him with, “Hey, mister, give me a dollar,” Boland thoroughly despised her.

Boland didn’t know what to believe anymore. At the end of the school year, he quit.

Toward the end of his tenure, Boland asked his sister Nora, a longtime teacher, for help. What was he doing wrong? What could he be doing right? Why couldn’t he break through to these kids, even the ones who seemed to care? How can society absorb such a massive human toll?

“I’ve been teaching for a long time now,” Nora told him. “And my only answer is that there are no easy answers.”

* Boland might rather have looked at some more realistic options to explain his students’ behavior—the fact that according to all major studies, blacks in America have an average IQ of around 85, and Hispanics have an average IQ of between 85 and 87.

This is however still higher than blacks in sub-Saharan Africa (where the average IQ is 65). The higher black IQ in America is largely the result of white admixture, but is still more than a dozen points below the white US national average.

While low IQ alone is not a cause of criminal behavior, it is a major contributing factor, along with deficient understandings of morality, social behavior, and societal responsibility.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History