Daily Mail

January 27, 2014

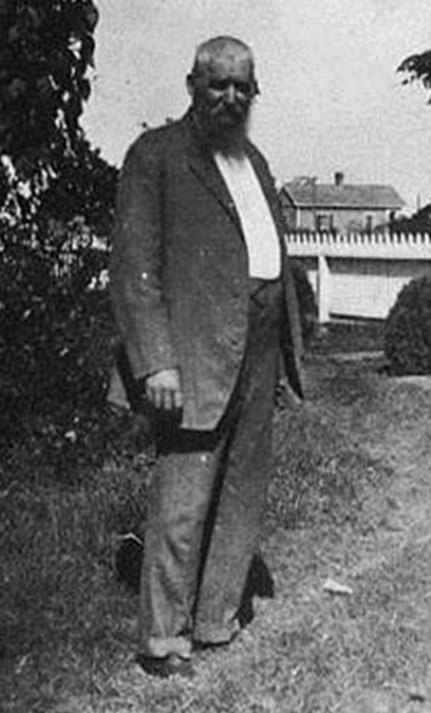

The respectable southern gentleman with a balding head, straggling white beard and a well-filled but slightly shabby suit hardly looks like the whip-wielding monster of plantation legend. Yet this is William Prince Ford, the Louisiana slave master at the heart of 12 Years A Slave, the blockbuster movie currently packing cinemas in Britain and America.

The film, based on the remarkable autobiography of free black American Solomon Northup, who was kidnapped in 1841 and sold into slavery in the Deep South, has been acclaimed as one of the most compelling accounts of the brutal slave era ever made.

The issue remains so politically toxic in the US that it took a British director, Steve McQueen, and a British star, Chiwetel Ejiofor, to bring the project to the screen. In the wake of great critical acclaim, both have been nominated for Oscars as part of an extraordinary total of nine nominations.

However, the film also has its critics, who say it ignores the kindness that Ford is known to have displayed towards his slaves and claim that the film-makers are promoting a distorted and simplified version of the truth.

Ford is played in the film by a frock-coated Benedict Cumberbatch. The Baptist minister and cotton-grower is portrayed as a pompous hypocrite; a weak-willed man unable to protect Northup and his fellow slaves from sadistic overseers in the cotton fields.

In the movie, Ford’s Christian sermonising is overlaid with the agonising screams of a female slave grieving for her stolen children, an effect aimed at underlining the minister’s double standards.

But Northup had little but praise for the clergyman who bought him for $1,000 at a New Orleans slave market and put him on a horrific path of servitude in which terrible injury and death were never far away.

In his memoir, published in 1853, Northup, who had been a prosperous married farmer and talented violinist in upstate New York before his kidnap, insisted: ‘There never was a more kind, noble, candid Christian man than William Ford.’

The faded photograph, the only known picture of Ford, shows him on his estate in Cheneyville, a village in dusty central Louisiana, and has been kept by members of his family.

They venerate him as one of the most generous and principled of slave owners in a terrible period in American history when a series of bloody slave rebellions had thrown the pre-Civil War South into turmoil.

The most serious of these was Nat Turner’s rebellion of 1831, when an armed band of slaves went on the rampage in Virginia, killing 65 people.

In the brutal reprisals that followed, 56 slaves were executed by the State of Virginia for taking part in the rebellion and an estimated 200 black slaves who had nothing to do with the conflict were killed by armed militias.

Across the South, laws were passed prohibiting the education of slaves and free blacks, and restricting their rights of assembly and other civil rights.

McQueen’s film spares little in its unflinching account of the events that cast such a long shadow over American society.

But critics of the film believe that his portrayal of Ford is little more than a cartoon characterisation, simplifying the realities of life in the slave-era Deep South.

Many of Ford’s descendants still live in the Cheneyville area and some were tracked down by The Mail on Sunday.

One was his great-great-grandson, 77-year-old William Marcus Ford, who described the film as ‘too dark and exaggerated’.

He added: ‘By all accounts, my great-great-grandfather treated his slaves well and did his best for them.

‘He was born at a particular time in history when slavery was accepted throughout the South.

‘It wasn’t illegal. That doesn’t make it right or moral by today’s standards but back then it wasn’t an ethical issue. Northup saw him as a kindly person. He was a highly moral man.’

The film, says Mr Ford, ignores the fact that ‘slaves were regarded as valuable pieces of property and that it wouldn’t be in an owner’s interest to treat his slaves badly’.

He said: ‘Good field-hands had worth. They were valued. A skilled craftsman like Northup would have been valued. There might have been a few bad apples, but I don’t think there was widespread brutality.’

While it is true that the white Establishment of the Deep South has a long history of attempting to minimise the region’s brutal history, independent experts concur that William Prince Ford treated his slaves with at least a modicum of respect and kindness.

Charles Neal, an assistant director of the Louisiana History Museum, said he was ‘horrified’ by the unremitting scenes of brutality in the film.

‘It was evil white folks beating on poor black folks and it’s not what Solomon Northup intended when he wrote his book,’ he said.

‘He thought Ford was a really good master. He was treated right and he was treated like family.’

Indeed, Northup recalls in his book that the minister rescued him from a lynching and instructed him on how, if he led an ‘upright and prayerful life’, he would be rewarded in the next life in heaven. Ford even gave him as a gift a fiddle, which he played at neighbouring plantations, as seen depicted in the film.

But this was a time when the southern states were gripped by mounting fear of their own slave populations, and Louisiana historian Frank Eakin pointed out that Ford may have had other motives for trying to treat his slaves well. ‘Violence had worked in the past as a means of control but now the worry for slave-owners like Ford was that if you were violent to a slave, he might kill you,’ he said.