Andrew Joyce

Occidental Observer

February 6, 2015

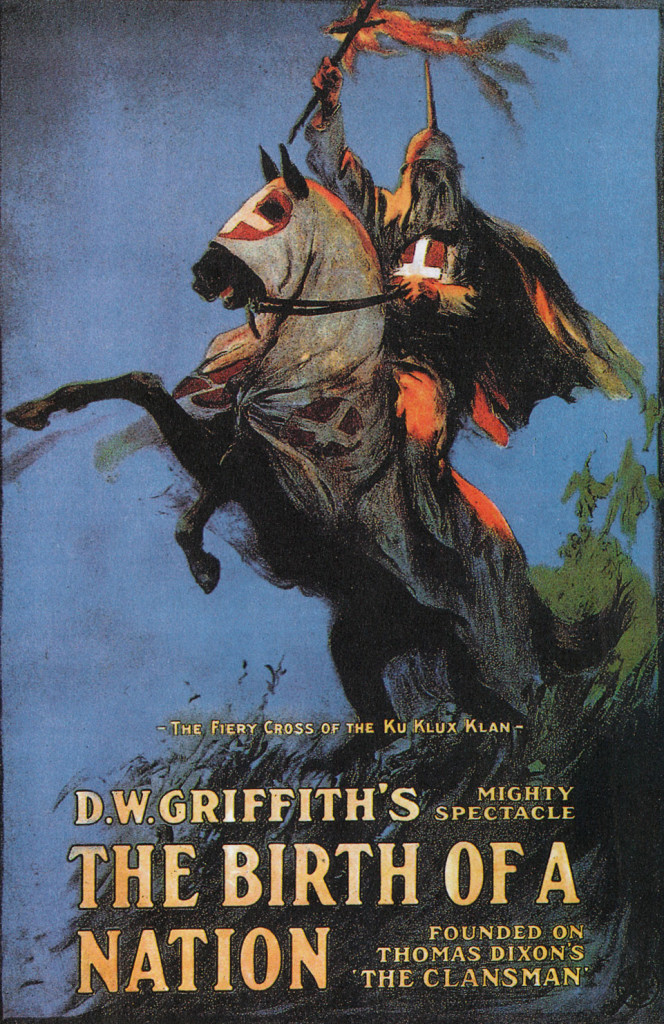

Liberals and multiculturalists hate it when confronted with works of obvious genius which don’t fall into the pattern of their worldview. Along with angst-fuelled hand-wringing over certain works by Shakespeare and Wagner, a more modern manifestation of the problem is the cinematic landmark, The Birth of a Nation, which will quietly celebrate its centenary this week. Compelling, innovative, trend-setting, and epic in scale, D.W. Griffith’s astonishing and unflinching vision of the Civil War and Reconstruction-era South remains powerful viewing even on its hundredth birthday.

I was an impressionable eighteen-year-old college student when I first viewed it. Despite the admonitions and careful commentaries of my film and media professor, I remember seeing past the fact that it was silent and interspersed with grainy captions and being impressed by its ‘modern’ style and appearance, and the smoothness of the editorial process. But it was some years later before I came to truly appreciate the scale and meaning of what Griffith had committed to film. On this occasion I watched it in North Carolina, at the home of my wife’s very elderly grandfather. This remarkable old man was every inch a Southerner, and a true gentleman at that. There one humid May evening, with the AC broken down and the windows wide open, the old man pulled out some Civil War relics that he had collected over the years. Presenting a series of antique rifles, medals, and pictures of Lee and Jackson, his eyes regained a youthful spark as he spoke of his own family memories and connections (real or imagined) to a host of Confederate heroes. Later in the evening, after we set down the relics of war in favor of cigars and Scotch, he pulled out a dusty VHS from an old bookcase. It was Birth of a Nation. It’s a long movie, clocking in at over three hours, and the old man drifted off to sleep within the first half hour. But I kept watching. And it was that night, with the firebugs glowing and buzzing by the open windows, and with the fragrant Southern air drifting slowly inside, that I felt what Griffith had aimed to portray — pride of land, pride of culture, and pride of blood.

This kind of pride, of course, and the connected desire to protect and preserve what one is proud of, is anathema to our enemies and those of our own race and culture who follow a different worldview. But they clearly have a hard time simply dismissing prideful cultural products which are so clearly manifestations of great genius and sublime art. Griffith sought out realism like no other previous director, using consultants from West Point Academy to make the battle scenes as realistic as possible. Most of the uniforms worn by the actors were authentic uniforms used in the actual Civil War. As an editor, Griffith broke free of the prevailing “filmed stage play” paradigm of static filmmaking and used flashbacks and parallel scenes to provide a sense of simultaneous action that made film (for the first time) completely different than live theater. The quick cuts of movies, television, and even advertising today owe their beginnings in many ways to Birth of a Nation. Similarly, the evocative, inspiring modern movie score has its roots in Birth of a Nation, which featured a full, three-hour score full of original music, contemporary standards such as (the unavoidable) “Dixie,” and classical music such as Richard Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries. The juxtaposition of technical brilliance and racialist subject matter, however, makes for uncomfortable viewing among liberals and opponents of White identity. Media site A.V. Club, one of the very few media outlets to even mention the centenary of Birth of a Nation, remarks:

As far as problematic art in America is concerned, Birth of A Nation is the closest thing there is to a dictionary definition example, mostly because American culture has had a really hard time letting it go, or has turned not letting it go into a critical art in and of itself. Birth of A Nation is the movie where many of the values associated with ,American filmmaking—complex intercutting, massed crowds of extras contrasted with close-ups of actors, carefully edited suspense and chase scenes—get their first really clear, fully formed expression. It’s also unquestionably white supremacist and racist. It represents a key point in the history of American art, and is animated by some of the ugliest rhetoric America ever produced. You can’t write a history of American movies—or movies in general—without mentioning Birth of A Nation. That’s not really what I want to talk about here, though. What I want to talk about instead is an idea that’s also connected to Birth of A Nation, which is the idea that art or entertainment can be aesthetically good while being ideologically bad—an idea that’s kind of intoxicating, because it suggests that it’s possible to navigate a movie on form alone, and also deeply problematic, because it’s founded on the notion that style and content are two different things, rather than different ways of looking at the same object.

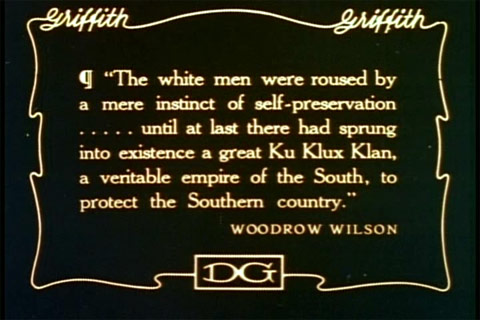

The movie premiered on February 8, 1915, in Los Angeles, and tickets were sold at the then-record $2 ($46.88 today). At that time, it was called The Clansman, and was based heavily on the best-selling 1905 novel of the same name by Thomas Dixon. In Griffith’s own words, when his assistant Frank Woods brought him the The Clansman, he “skipped quickly through the book until I got to the bit about the Klansmen, who according to no less than Woodrow Wilson, ran to the rescue of the downtrodden South after the Civil War. I could just see these Klansmen in a movie with their white robes flying. …We had all sorts of runs-to-the-rescue in pictures and horse operas. … Now I could see the chance to do this ride to the rescue on a grand scale. Instead of saving one little Nell of the Plains, this ride would be to save a nation.”

And this, essentially, is what occurs. The movie climaxes, famously or infamously depending on your worldview, with two attempted rapes of White women by Black men and the subsequent reaction against Black political and sexual revolution by the white-robed Knights of Christ.

The essence of the film was bound up to some extent with the inter-connected personal histories and experiences of the three major figures in its production and dissemination: President Woodrow Wilson, author Thomas Dixon, and film-maker D.W. Griffith. All three were Southerners who had moved north at the end of the nineteenth century. Dixon and Griffith had known each other as John Hopkins students. After Dixon became a minister, and Wilson a professor, Dixon nominated Wilson to receive an honorary degree at his own undergraduate alma mater, Wake Forest. “He is the type of man we need as President of the United States,” Dixon wrote to the board of trustees. Dixon later resigned as a minister to become a writer; and Griffith (before he turned to movies) acted in some of Dixon’s earliest plays. Griffith later used The Clansman, Wilson’s History of the American People, and other materials provided by Dixon as sources for Birth of a Nation, and Griffith and Dixon worked equally hard to make and promote the movie. One of its first viewers was Wilson, who watched it at the White House shortly after the death of his wife. To Wilson, the movie was “like writing history with lightning … and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.” Wilson later permitted his endorsement to be used to promote the film, until he succumbed to tremendous pressure from early multiculturalist organizations to distance himself from it.

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History

Daily Stormer The Most Censored Publication in History