Andrew Anglin

Daily Stormer

February 20, 2020

Gremlins is a 1984 comedy-horror film directed by Joe Dante and written by Chris Columbus.

This is in many ways the ideal film. Although there are some minor pacing issues (which were deliberate), and multiple serious plot problems (which do not appear to have been deliberate), there is very little to criticize it for in terms of overall execution. The story, characters and dialogue are ideal, and the direction, cinematography and effects are perfect. The actors are all perfectly cast.

There are several subplots set up which do not ever materialize – the primary example being some evil plan by an old woman and the bank to destroy people’s homes, which just disappears – but somehow they managed to spin it into a coherent whole, where the lost plot points are not missed.

The highlights of the film are the soundtrack and the puppets themselves, which stand out despite the fact everything else is so well done. The creatures were designed by Chris Walas, who also designed the creatures in The Fly. These creature effects were certainly improved in the second film, where multiple Academy Award winner Rick Baker took over effects direction, but his designs all stemmed from Walas’ work. The Gremlins in the film are created with a mix of hand puppets, animatronics and marionettes.

On a personal level, I would possibly take issue with the association of horror imagery with the idyllic scene of a white Christmas in a small town. All things being equal, I think that the themes of Christmas should be held sacred in our society, and using the setting of Christmas as the scene of an attack by reptilian monster creatures is rebellious and socially negative. That having been said, my personal thoughts on the setting are not relevant to a judgement of the overall quality of the film.

The film is both a parody and a homage to previous horror films, but has no problem standing on its own even if you are not a fan of that genre. Furthermore, it manages to maintain both comedy and horror elements without the comedy seeming too dark or the horror seeming too silly.

Gremlins was a major box office success, making $153 million at the box office against a budget of $11 million. (For comparison, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, released the same year, made $330 million against a budget of $28 million, meaning the per-dollar return was bigger for Gremlins.)

The film starts with Billy’s father Rand Peltzer (Hoyt Axton) going to Chinatown to buy a special Christmas gift for his son.

An ominous old Chinese man has a creature in a box, which we do not yet see, which Rand is interested in purchasing.

The Chinese man refuses to sell the creature, saying it is too dangerous. But the Chinese man’s grandson meets Rand outside and sells it for $200.

The opening scene is quite beautiful, and we see the large name of Steven Spielberg. This whole thing where a famous director produces something and then puts his name on it to trick people into thinking he directed it is a bit shady, I always thought. Producers do very little creatively and are more likely to hurt the vision of a director than improve upon it.

The fake snow is not very good, and one of the only effects-related problems in the film. Although in theory, that could be viewed as adding a certain mood of stylistic unreality to the film, given that it looks quite a bit like the snow of classic claymation Christmas specials.

A feature throughout the film is that mechanical things do not work, and we get a great shot early on of Billy trying to fix his broken Volkswagen bug.

Thematically, it doesn’t make sense that things are breaking before the Gremlins show up. For those who might not be familiar, “gremlins” were something that WWII soldiers blamed for malfunctioning machinery, and that concept goes throughout the film.

In his book “Rebels Against the Future,” intellectual Luddite Kirkpatrick Sale actually went so far as to label this film “anti-technology,” alongside E.T., War Games and Return of the Jedi, due to the themes of things breaking down and thwarting the plans of the characters.

There is a shot of the theater where the marquee reads “A Boys Life” and “Watch the Skies,” which are the original titles of E.T. and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, respectively.

One of the charming things about the film is that despite the unwholesomeness of the potentially anti-Christmas theme, Billy Peltzer (Zach Galligan) and Kate Beringer (Phoebe Cates) are the embodiment of wholesomeness.

Phoebe Cates is lovely, and an argument for solving the Jewish problem by forcing them to breed with Filipinos. It would apparently at least solve the problem of their looks, though it is possible that Cates is not, in real life, as wholesome as Kate Beringer. Though I did believe she was.

I suppose her role in Fast Times at Ridgemont High (a terrible film made by Holocaust survivors) would disprove that theory.

Fellow Ridgemont alum Judge Reinhold is also in the film, playing his standard asshole character, this time a bank worker who humiliates Billy with his success.

Presumably, he was supposed to show up again in the film and get killed, and they forgot to include that. That is one of several notable problems with the film.

Billy is finally given the gift of the mogwai by his father, who tells him he must open it immediately.

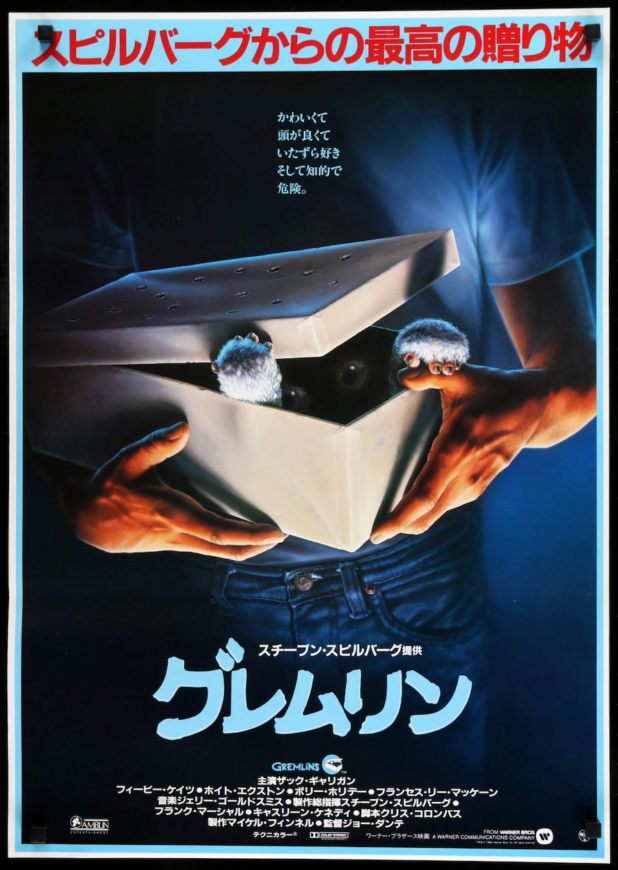

We are 20 minutes into the film and we finally see Gizmo for the first time, in the iconic “peeking out of the box” scene.

Billy is given the three rules for being a mogwai owner: Don’t expose him to sunlight, don’t get him wet and don’t feed him after midnight.

A running gag is Rand’s dumb inventions, none of which seem to work. The gags always work, however. And without CGI, they’re a lot of fun.

The film spends about half of its run time getting to the second act, but the water is quickly spilled on Gizmo by none other than Corey Feldman.

When wet, Gizmo goes into convulsions, and little balls of fur pop out of his back.

The balls of fur get bigger and unfold, revealing themselves to be other members of the race of mogwai.

The scene of Billy and Corey looking at the creatures lined up on the desk was framed perfectly, and is another notable shot.

As a kid, I loved this film. As an adult, I am even more capable of understanding how creative all of this is. To have a furry creature bought from an old Chinaman that shoots other furry creatures out of its back when it gets wet, and to have all of this accepted by the people witnessing it, is really like a classic fairy tale.

Billy tells his father about the multiplication, and his father wants to claim them as his invention and make sure every kid in America gets one.

The new mogwais, however, are not like Gizmo, but are mischievous and cruel. Critics of the film have claimed that it is obvious that the filmmakers intended for the Gremlins to represent black people, due to their criminal nature and their love of fried chicken.

This claim of racism was included in the anti-white hate film “Dear White People” and despite the fact this film was made in 2014, it was considered to be funny enough to include in the trailer.

While Gizmo sleeps in Billy’s bed, the mischievous new mogwai sleep together in a row on the floor with a blanket.

They begin sneaking out at night to engage in mischief, including tying up the family dog in Christmas lights.

Billy takes one of the mogwai to a black science teacher at the local high school, who true to horror movie tropes, becomes the first person to die due to his own irresponsibility.

Classic horror bit actor Dick Miller is in the film as Murray Futterman, an old man who hates foreigners and keeps talking about how the technology of the film doesn’t work because it is made by foreigners.

The scene with Billy and Kate walking home together from her work, where Billy at the end gains the courage to ask her out, is as wholesome as anything in “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

And it is hilarious when Kate says “suicide rates are highest around the holidays… while many are opening their presents, some are opening their wrists.”

The contrast between this wholesomeness and the gruesome nature of the creatures and the violence is on purpose, but again, none of the wholesomeness appears silly or forced or simply there to justify a bit. This is entirely legitimate wholesomeness.

Billy mistakenly feeds the mogwai fried chicken after midnight, because the bastards had chewed the cord of his clock so he didn’t have the correct time.

Just so, the irresponsible black scientist accidentally leaves a sandwich for the mogwai that Billy left for him to study.

The next morning, the science teacher wakes up to find that his mogwai is now in a cocoon.

And all of them at Billy’s house are in the same condition.

Although this is halfway through the film, and yes, that is a long time to spend getting to the second act, the structure of the plot does not suffer because of this.

When the trouble begins, Rand is at an inventors’ convention, where he is distressed by the competition. He keeps calling home from a phone booth.

Billy’s mother is the only one home when the cocoons open.

Gizmo, who did not eat after midnight and is thus still a cute and furry creature, is shown being tortured in various slapstick ways.

The Gremlins are fundamentally Faustian trolls, as everything they do is purely for the lols, that they may transcend form through lols.

The shot of Billy running out of the school in the snow to go help his mother was beautiful, and like many scenes in this movie, reminded me of the best parts of my own 1980s childhood in the Midwest.

The first full shot of the now reptilian Gremlins is seen when Billy’s mother walks in to find one in her kitchen, leading to the second best scene in the film.

He is eating the gingerbread cookies – but only their heads.

He climbs into a blender and she does the apparently obvious thing and turns it on, grinding the creature up and spitting green blood all over the place.

Another she traps in a microwave and turns the microwave on, causing the creature to pop.

With two knives in hand, she moves to search the rest of the house, and she is attacked by a Gremlin hiding in a Christmas tree.

Billy rushes into the house and picks up a sword that his father keeps mounted to the wall, and slices the Gremlin’s head off. The head ends up in the fireplace, where it burns up.

This was one of the scenes that I felt associated beloved Christmas imagery with terror in a way which I viewed as socially negative. But it was otherwise a funny scene.

This film got a lot of backlash for the violence in it, with parents who brought their children getting up and walking out of the theater. In 1984, there was no PG-13 rating, so apparently people got the impression that this film was safe for small kids. In response to the backlash, Steven Spielberg came up with the idea of a middle ground rating between PG and R, and they quickly introduced PG-13 films.

For those of you with children, I would say that the content is fine for anyone over 10, but I wouldn’t recommend showing it to children because of what I view as a defilement of Christmas imagery.

After the confrontation with the mother, the ringleader of the Gremlins, Stripe, is the only one living.

He flees the home and Billy somehow tracks him to the local YMCA.

How he was able to find him at the YMCA was not clear. It’s a minor plot problem, but I did note it. It should have been easily solved by having Billy swipe him with the sword before he got away, which would allow for him to then follow a trail of green blood.

Billy finds Stripe near the pool, and he jumps in, causing the water to bubble and smoke and turn green.

This was a scene that really reminded me how much more interesting it was to watch a movie before CGI. This is the kind of thing that you have to sit there and think about how it was done (I think it was done with jets; I doubt they boiled the pool, but I would have to watch the DVD commentary to know for sure).

By jumping in the pool, Stripe used his own body to create an entire army of reptoid-type Gremlins, who move out from the YMCA to take over the town.

As the chaos is beginning, Murray is at home messing with his TV set that has stopped working. He blames it on the fact that the TV is foreign.

He goes out to check the antenna, which has been pulled down by the Gremlins. He finds that they’re in his truck.

They drive the truck straight through his house. And it is the funniest thing ever the way the Gremlins are just laughing about the mayhem. They’re the embodiment of fairy tale creatures of mischief.

This is the first time we hear the film’s fantastic theme song.

Meanwhile, Billy has gone to the police, who do not believe his story. Hilariously, one of the cops is played by Jonathan Banks, who played retired cop Mike Ehrmantraut in Breaking Bad.

The cops leave when they get a call about Murray’s house being destroyed, and chaos is engulfing the town as the Gremlins run amok. There are several bits here that while funny are disrespectful to Christmas imagery, in my view.

The Gremlins manage to get the evil old woman to go insane, saying “they’ve come for me!” and accidentally turning her stair lift up so high it launches her out the window.

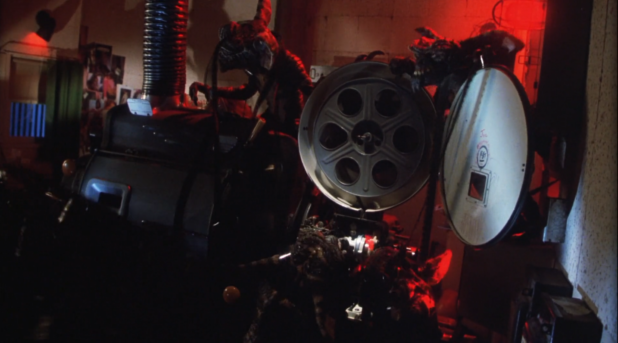

My favorite scene in the film is the bar scene, where Kate is forced to serve drinks to the Gremlins. It is a hilarious slapstick event, with all of these puppets engaging in various degenerate acts and referencing various films.

This is where flasher Gremlin appears, opening his trenchcoat to show Kate his smooth reptoid crotch.

Kate eventually figures out that she can use a Polaroid camera as a weapon, as the creatures are allergic to light.

At the door is a Gremlin in a ski mask with a gun who is definitely a reference to black people.

Billy comes to save Kate, and they make it to a bank, and Kate takes this moment to tell Billy the story of why she hates Christmas.

She explains that on Christmas when she was five years old, her father disappeared. Five days later, there was a smell coming from the fireplace, and they found that her father had broken his neck and died as he was attempting to bring Christmas gifts, dressed as Santa.

The producers, including Spielberg, tried to get Joe Dante to remove this part from the film, saying that it was confusing as to whether it was supposed to be funny or sad. Dante pushed back and refused to have it removed, saying that the fact that you can’t tell if it is funny or sad was representative of the whole film.

The pair go outside, and find the Gremlins gone from the streets. They realize that they’ve gone to the theater to watch Snow White.

Billy successfully manages to blow up the theater, killing all of the Gremlins.

All except Stripe, who left the theater in search of candy.

With Billy coming after him, Stripe takes off on a skateboard into the department store.

The skateboard shot was the most visually awkward shot of a Gremlin in the whole movie, because the hand puppet was switched out for a marionette, but watching him escape on the skateboard carrying his candy was funny enough to make me laugh aloud.

During the final showdown, Stripe grabs a gun and fires on Billy as he is trying to get into a fountain to reproduce more Gremlins.

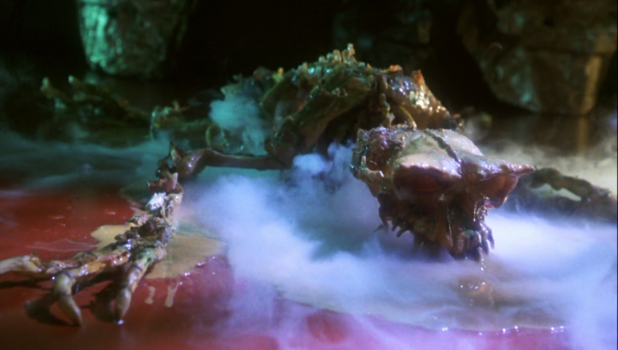

Gizmo comes to the rescue, in a pink car, and is able to open the windows and cause the sun to shine on Stripe, which causes his skin to melt.

After he’s melted, he crawls out for one last gasp, and it is nothing but his skeleton.

I was impressed with the fact they actually made the skeleton and then figured out a way to make it melt.

The film ends with all being well, but the old Chinese man comes to Billy’s house and takes Gizmo back, saying that white people are not ready for such a creature.

This vague afterthought of a faux-moral to the story – delivered to them by an old Chinese man – is clearly poking fun at the idea that a story should need a moral, saying “we’re smart people, but we can just have fun if we want,” and that is as close as you get to a message of any kind in this film.

He then walks off into a painting.

This is a film from another time, when the entire world was completely different. There isn’t any heavy content in it, and that is itself representative of a time when a film could be made without six million different subtle and aggressive implications. It is akin to Grimm’s Fairy Tales, a simple story of mystery and monsters, horror and humor, where seemingly senseless tragedy happens but everything works out in the end.

It was exclusively designed for the purposes of fun and entertainment, but manages to take that modest goal and create a great piece of art that puts the whole of modern cinema to shame. If you take it apart, nothing about it is especially remarkable, but the end product is something magical that stayed with me as a child and has not lost any of its power now.

I enjoyed watching a movie from the year I was born, and I might watch more films from this era and write reviews.

Click here for more film and television reviews.